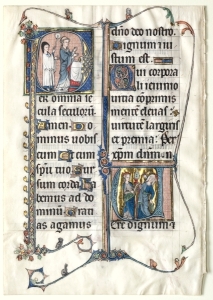

The Flight into Egypt, Walters Art Museum, MS W.188, f.112r

If you’ve been travelling with me on this virtual road trip around the United States, you have almost certainly come to know the dismembered beauty known as The Beauvais Missal. I’ve mentioned it many times and shown you several different leaves found in various collections. And I’ve ruminated about the possibility of digitally reassembling this masterpiece of thirteenth-century illumination. Well, it’s time to stop dreaming and start doing.

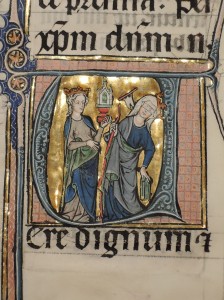

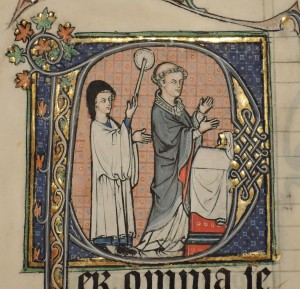

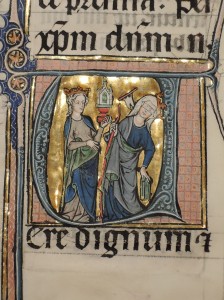

Cleveland Museum of Art, Acc. 1982.141 verso

Working with the “Broken Books” project at St. Louis University, I have begun a digital reconstruction of the Beauvais Missal. The “Broken Books” project will result in the development of a platform for reconstructing broken books as well as the establishment of a metadata structure designed specifically for manuscript fragments and leaves. My Beauvais Missal project will serve as one of several case studies in the project’s early stages.

The Beauvais Missal (also known as the Hangest Missal) has been much studied, by scholars such as Barbara Shailor, Christopher de Hamel, Anthony Edwards, Alison Stones, and Peter Kidd, among others. You’d think there couldn’t possibly be anything more to discover about it. But for all the times it’s been mentioned in print or online (try Googling “Beauvais Missal”), there is still much to learn about its contents and history. I’m working on the former, and Peter Kidd has recently filled in some of the missing pieces of the latter, allowing us to reconstruct much of the manuscript’s pre-biblioclastic journey; see his recent blogposts here and here.

To sum up:

- The manuscript was written for the use of Beauvais in the late thirteenth century and is said to have originally been the third of a three-volume set. The codex originally comprised 309 leaves. No one has ever identified the other volumes of the set.

- Given to the Beauvais Cathedral in 1356 by Robert de Hangest, a former canon, to ensure that his death would be commemorated every year. We only know this because the donation inscription was transcribed by later catalogues; the leaf preserving the inscription was lost when the manuscript was dismembered.

- The manuscript is recorded in the Beauvais Cathedral library as late as the seventeenth century. It is unclear when the Beauvais Cathedral library was dispersed, but, like many early French libraries, the collection was probably broken up soon after the French Revolution.

- Owned by Didier Petit de Meurville (1793-1873), of Lyon; his sale, 1843, lot 354;

- Owned by four generations of the Brölemann family: Henry-Auguste Brölemann (1775-1854) of Lyon; his son Emile-Thierry Brölemann (1800-1869); his son Arthur-Auguste Brölemann (1826-1904); his sister Albertine Brölemann (1831-1920); her daughter Blanche Bontoux (1859-1955), sold by her at Sotheby’s, 4 May 1926, lot 161, to;

- William Permain, as agent for;

- William Randolph Hearst (1863-1951);

- Sold from his collection in October 1942 through Gimbel’s NY, to;

- NY bookdealer Philip Duschnes (1897-1970), who cut it up and sold many of its leaves to;

- Otto F. Ege (1888-1951). Ege went to on give away or sell many leaves of the manuscript. Single leaves of the Beauvais Missal are best known as No. 15 in the “Fifty Original Leaves of Medieval Manuscripts” portfolios, of which forty were issued.

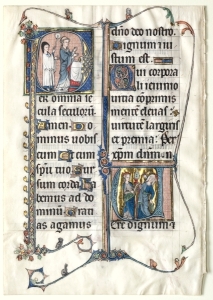

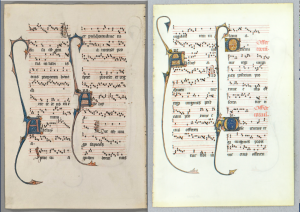

Harvard Univ., Houghton Library MS Typ 956 2 verso (left) reunited with its originally consecutive leaf, sold at Christie’s on 4 Sept. 2013, lot 262 1 (at right). Note the gold offset in the upper right corner of the Houghton leaf, matching the decoration in the upper left corner of the Christie’s leaf.

I’ve made a lot of progress already, identifying the contents of more than 80 known leaves, pairing up consecutive leaves, reconstructing quire structure. There are no folio numbers, but the contents are in liturgical (calendrical) order. The trick is identifying the feastday if there are no rubrics. Liturgy, it turns out, is quite Google-able. In addition, the gold decoration sometimes leaves mirror-image offsets on formerly-consecutive leaves, where the leaves were pressed together during the centuries when the book lay closed (example above).

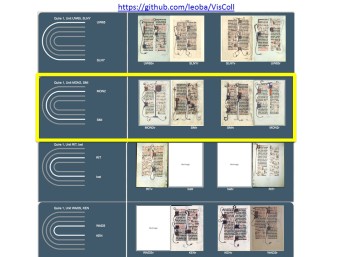

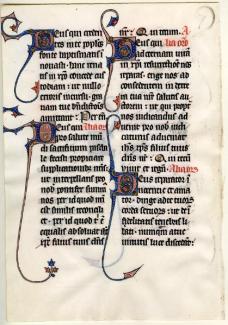

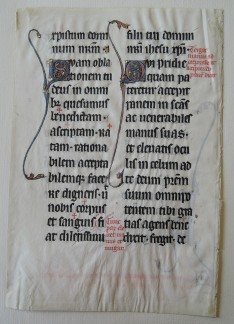

I’m not quite ready to share all of my observations about the manuscript, but one thing is clear from the work I’ve already done on the contents of each leaf: the Beauvais Missal was a summer volume, preserving Mass texts and chant for feasts falling between the week after Easter and the end of November. The manuscript also included a calendar, a section of special masses, and the Canon of the Mass (whose leaves have only fifteen lines of text as opposed to the twenty-one lines elsewhere in the manuscript; see the Cleveland Museum of Art leaf above).

The virtual reconstruction of this manuscript is of course only possible because of recent advances in the field of digital humanities, in particular database structure, image annotation, and the encoding and interoperability of both.

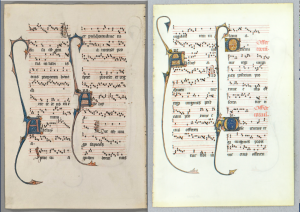

Priest praying over the Host (Oberlin College, Allen Memorial Art Gallery, Acc. 1993.16 recto, detail)

But it is the very materiality of medieval manuscripts that makes them so magical. As anyone who has touched a 1,000-year-old manuscript can attest, knowing that you are reading a page written, held, read, and passed on by generations of humans is an extraordinary experience. As manuscript scholars and digital humanists, we should never lose sight of the ultimate, essential reality: these are books, meant to be touched and read and handled (unless, of course, a curator or conservator decides otherwise). A digital surrogate can only take us so far.

Priest saying Mass (Cleveland Museum of Art, ACC. 1982.141 verso, detail)

A digital image can’t tell you how each side of the parchment feels, it can’t show you how to definitively distinguish the hair side from the flesh side, a distinction of critical importance for understanding the structure of a medieval manuscript. Sometimes images are cropped, because the photographer doesn’t know that the margins of the leaf may be just as important as the text; in the case of the Beauvais Missal, uncropped edges may include important physical clues about the binding structure, such as sewing holes or evidence of repairs. Effaced inscriptions or annotations often can’t be read in a standard image and need to be examined in situ, using multi-spectral imaging techniques if you’re lucky enough to have access to such equipment. These are just a few examples of the kind of evidence that only a physical examination can uncover. In order to completely understand the original structure and binding and sequence of the leaves in the Beauvais Missal, I need to study as many leaves as possible in person.

And so a few weeks ago I embarked on an actual – rather than a virtual – road trip, visiting twelve of the fifteen Beauvais Missal leaves currently residing in Ohio. It was a whirlwind tour as I visiting eleven collections in four days, but I didn’t need much time with each leaf. I put a thousand miles on my rental car, driving from Cleveland to Columbus to Toledo before getting back to my day job and heading for the Annual Meeting of the Medieval Academy of America at the University of Notre Dame. All of that driving was well worth it. I saw several leaves I hadn’t known about, took high-resolution images of leaves for which I didn’t have good images already, saw old friends, and got to know collections that were new to me.

Ecclesia and Synagoga (Cleveland Museum of Art, ACC. 1982.141 verso, detail)

I saw the highlights of the manuscript on my first day. The 1926 Sotheby’s catalogue describes the Missal as having four historiated initials. Three are in north-east Ohio: two on a leaf at the Cleveland Museum of Art (above and at right) and one on a leaf at the Allen Art Gallery at Oberlin. The fourth, probably from the Te Igitur section of the Canon, is lost. It is no co-incidence that so many leaves of the manuscript, including both surviving historiated leaves, can today be found in Ohio, since that state was Otto Ege’s home turf.

Over the next few days, I visited Kenyon College, the Cleveland Public Library, a private collection in Oberlin, the Cleveland Museum of Art, the Ohio State University, the University of Ohio, and the Toledo Museum of Art. I had to skip a few Ohio collections for want of time, so I chose not to visit collections whose leaves had already been photographed at high-resolution: Case Western Reserve University, Denison University, and the Cincinnati Public Library. My thanks to all of the librarians and curators who so generously shared their material with me.

Two Ohio collections with Ege material are particularly noteworthy: The Rowfant Club in Cleveland and the Lima Public Library. These collections could not be more different – an urban bibliophilic men’s club and a small public library in the middle of farm country – and yet both institutions were important to Ege.

Beauvais Missal leaf, Rowfant Club, Cleveland

In 1940, Ege was elected an honorary member of the Rowfant Club, and he probably donated their Beauvais Missal leaf at some point in the 1940s. The leaf at the Rowfant Club has been hiding in plain sight for decades, prominently displayed in a custom pivoting wall-mount in the doorway of the main meeting room (at left). The bookcases along the walls are filled with tall candlesticks, of great significance to the members. When a gentleman joins the Rowfant Club, he selects a candlestick to serve as his totem throughout his life at the club. It serves as his placecard at dinner and represents him in absentia. When he dies, the members gather to memorialize their departed friend, lighting and snuffing his candle before setting it upon a high shelf in perpetual remembrance.

Otto F. Ege’s Rowfant Club candlestick, as reproduced in the Club’s Candlestick Book.

Ege’s candlestick, of his own design, is shown at right.

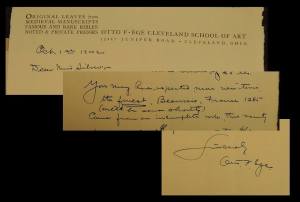

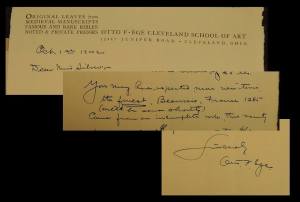

Ege’s relationship with the Lima Public Library was of a fiscal nature. He worked out an arrangement with the Library whereby they would act as his local agent, selling medieval manuscript leaves on his behalf and keeping a portion of the proceeds to benefit their Staff Loan Fund. This arrangement lasted for several decades, to the benefit of all parties. During my morning in Lima, the librarian very kindly showed me several thick folders of correspondence between Ege and the Library stretching across decades. I was very excited to find this very early reference to the Beauvais Missal, a letter to the Lima librarian dated 1 October 1942 in which Ege writes, “You may have expected nine new items, the FINEST, Beauvais, France 1285 (will be sent shortly)…”

Lima Public Library, 1 Oct. 1942 correspondence between Otto F. Ege and the Lima librarian.

This letter (shown at left) was written several weeks BEFORE Duschnes bought and dismembered the manuscript, suggesting that he and Ege decided in advance to buy, and to break, the Beauvais Missal. And now, seventy-three years later, it’s time to put it back together.

[note: the following paragraph and the list below have been updated as of 15 July 2015]

So far, I’ve assembled images and metadata for 93 leaves (some now lost), representing twenty-two states and six countries. Several of the leaves in private hands were brought to my attention by Peter Kidd, to whom I am most grateful. I’m happy to share my handlist here – the largest list of Beauvais Missal leaves ever compiled:

Beauvais Missal Leaves in the United States

United States

AZ Phoenix Phoenix Public Library

CA Los Angeles [private collection]

CO Boulder Univ. of Colorado

CT Hartford Wadsworth Athenaeum

CT New Haven Yale University (2 leaves)

FL [private collection] (2 leaves)

FL St. Petersburg Museum of Fine Arts

IN Bloomington Lilly Library, Indiana University

IN Indianapolis Indianapolis Museum of Art

KY Louisville The University of Louisville

MA Amherst Univ. of Massachusetts, Amherst

MA Boston Boston Public Library (2 leaves)

MA Cambridge Houghton Library, Harvard Univ. (2 leaves)

MA Northampton Smith College

MA Northampton Smith College Museum of Art

MA Wellesley Wellesley College (2 leaves)

MD Bethesda Private Collection

MI East Lansing Michigan State Univ.

MI Kalamazoo Western Michigan Univ.

MN Minneapolis Univ. of Minnesota

NC Greensboro UNC-Greensboro

NH Hanover Dartmouth College

NJ New Brunswick Rutgers University

NJ Newark Newark Public Library

NY Albany State Library of New York

NY Buffalo Buffalo and Erie County Public Library

NY Hamilton Colgate Univ., Picker Art Gallery

NY New York Metropolitan Museum of Art

NY New York Morgan Library

NY Rochester Rochester Institute of Technology

NY Rochester Sibley Music Library, Eastman School of Music (2 leaves)

NY Stony Brook SUNY Stony Brook

OH Athens Ohio University

OH Bath Private Collection

OH Cincinnati Cincinnati Public Library

OH Cleveland Case Western Reserve University

OH Cleveland Cleveland Museum of Art

OH Cleveland Cleveland Public Library (2 leaves)

OH Cleveland Rowfant Club

OH Columbus The Ohio State Univ.

OH Granville Denison University

OH Kent Kent State University

OH Kenyon Kenyon College

OH Lima Lima Public Library

OH Oberlin Allen Memorial Art Museum

OH Oberlin Robert and Gina Lodge

OH Toledo Toledo Museum of Art

PA Bryn Athyn Glencairn Museum (2 leaves)

RI Providence Rhode Island School of Design

SC Columbia Univ. of South Carolina

TN Memphis Rhodes College (2 leaves)

VA Great Falls Private Collection (formerly Charles Edwin Puckett, Bookseller)

VA Roanoke Hollins Univ. (2 leaves)

WA Seattle Univ. of Washington

Canada

ONT Toronto Art Gallery of Ontario

ONT Toronto Ontario College of Art and Design

ONT Toronto Univ. of Toronto

SASK Saskatchewan Univ. of Saskatchewan

England

Christopher de Hamel

[Private collection outside of London] (sold Sotheby’s London 7/10/2012, lot 2a)

[Private collection in Yorkshire, RMGYMss]

[Private collection]

Japan

[Private collection]

Monaco

[Private collection] (three leaves, bought at: Christie’s 09/04/2013, lot 262, no. 3; PBA Galleries, Auction 540, lot 200; and Mackus Company)

Norway

Oslo Schoyen MS 222 (2 leaves)

As many as thirty leaves are known but untraced, including:

Christie’s 01/30/1980, lot 212

Christie’s, 06/25/1997, lot 16

Christie’s 09/04/2013, lot 262, nos. 1 and 2 (ex-Vershbow, later Pirages)

Bauman Rare Books

Bruce Ferrini Rare Books, Akron, Ohio, Catalogue 1 (1987), nos. 48-49 (2 leaves)

Endowment for Biblical Research, Boston University

Mackus Company, bookseller (1 leaf)

Maggs, London, Bulletin 11 (1982), no. 43

Quaritch, cat. 1270 (2000), nr. 79

Sotheby’s London, 11/26/1985, lot 61 (calendar leaf)

Sotheby’s London 12/5/1994, lot 4

Sotheby’s London 6/19/2001, lot 9

Also lost are Beauvais Missal leaves from twelve of Ege’s “50 Original Leaves” portfolios, numbered sets 1, 3, 4 (this set belongs to the Cleveland Institute of Art but is lacking its Beauvais Missal leaf), 7, 14, 18, 20, 21, 26, 31, 33, and 39.

I don’t have images of all of these untraced leaves, so it’s possible that some of these references are to the same leaf sold again. It’s been said that there is a leaf on the wall at the University Club in Chicago, but the staff of the Club assures me that even if there once was a leaf in their art collection, it is no longer there.

I hope to have a working online prototype of the digital surrogate by year’s end. I now appeal to my readers to help me find additional leaves. Here’s how to recognize them:

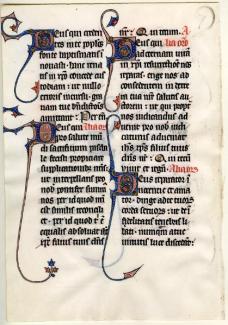

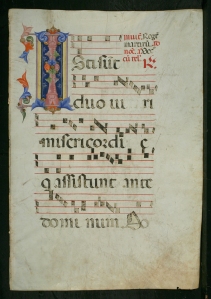

Typical Missal page (Case Western Reserve University, Ege MS 15 verso)

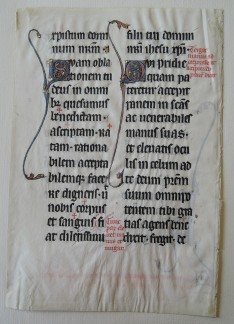

Typical Canon page (Cleveland Public Library MS Ege 15 verso)

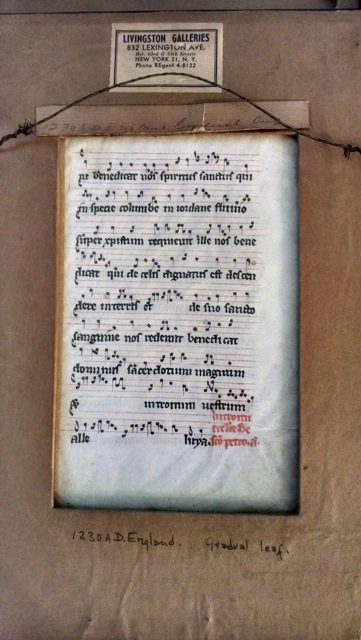

Typical Missal page with music (Michigan State Univ., Mapcase MSS 325, no. 2 recto)

In addition to the stylistic elements, which are certainly distinctive (in particular the leafy, pointed extensions into the margins), you can identify leaves of the Beauvais Missal by their dimensions. The leaves are written in two columns of 15 or 21 lines (or ten staves of music) per page, and the dimensions are around 290 x 200 mm (if untrimmed) with a written space of 200 x 135 mm. I am certain there are more leaves out there. If you think (or know) you’ve got one, or know of any I’ve missed, please contact me at LFD@TheMedievalAcademy.org!

The Beauvais Missal

The Beauvais Missal

The final leaf (shown to the right), from a large choirbook, cannot be positively identified in Gwara’s handlist, but it may be lurking in there somewhere.

The final leaf (shown to the right), from a large choirbook, cannot be positively identified in Gwara’s handlist, but it may be lurking in there somewhere.