As we leave the Berkshires, we’ll head due west on I-90, which, when it crosses into New York, becomes known as the New York State Thruway. Instead of turning south for Manhattan, however, we’ll keep going west (yes, there’s more to New York than NYC!), making our way (virtually, and therefore speedily) through central New York to Buffalo.

Not surprisingly, most medieval and Renaissance manuscripts in the United States are to be found in university Special Collections libraries. There are, however, about two dozen public (municipal) libraries that, through good fortune and/or generous donors, count pre-1600 manuscripts among their holdings. In fact, our data suggest that public collections in the US hold more than 500 pre-1600 codices and more than 800 single leaves. The largest of these collections belong to the New York Public Library and the Boston Public Library, but the Buffalo and Erie County Public Library in western New York is worth a visit, as it is an excellent example of a typical public collection.

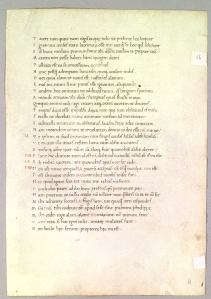

St. John the Evangelist (watched by his attribute, an eagle) in exile on the island of Patmos. (Book of Hours; mid-15th-century France. Buffalo and Erie County Public Library, Gluck Manuscript Collection)

The Grovesnor Rare Book Room at the Buffalo and Erie County Public Library is one of the oldest public rare book collections in the country, having been initially established in 1857 by Seth Grosvenor, a local businessman who bequeathed $40,000 to the city of Buffalo for the express purpose of establishing a public library. One of the earliest medieval acquisitions was this lovely two-volume Book of Hours written in mid-fifteenth-century France and given to the library in 1886 by James Fraser Gluck, a local attorney and library curator (more info here). Like most public collections, however, the B&E Library’s strength lies with manuscript leaves, not complete codices, most of which would be well beyond the purchasing power of a small public collection. The Library owns a set of fifty leaves assembled by Otto Ege and given to the library in 1964 by Mr. and Mrs. Franz T. Stone, called “Fifty Original Leaves from Medieval Manuscripts“; a second set of Ege leaves, “Original Leaves from Famous Bibles,” has a few manuscript leaves but is comprised mostly of pages taken from early printed books. All of the manuscripts have been catalogued in the library’s OPAC using MARC; you can easily retrieve the records, as the Library has established a local subject classification (in the 650 field) of “Manuscripts, Latin, New York (State), Buffalo.” Just search that as the Subject, and you will find twenty-five very informative records for all of the leaves and the lone codex (the Gluck Book of Hours illustrated above).

[Note to librarians considering putting medieval manuscripts into their OPAC: I heartily recommend establishing a local 650 field as it will allow users to easily filter your manuscript records. In MARC view, it could look like this: |a Manuscripts, Latin |z New York (State) |z Buffalo. I leave it to your cataloguing judgment whether to go with “Manuscripts, Latin” vs. “Manuscripts, Illuminated” vs. “Manuscripts, Medieval” or some such thing.]

There are a few other collections in Buffalo with pre-1600 manuscript holdings. Canisius College, a Jesuit university, still owns the five codices recorded in the de Ricci Census (II:1213-14). The Albright-Knox Art Gallery houses another collection of Ege leaves (including yet another leaf of the Terence manuscript we met at the University of Vermont a few weeks ago). A search of their database using the keyword “leaf” with date restrictions of 500-1500 will retrieve records for and images of all of the leaves, most of which can be readily identified as having an Ege provenance. The question of how manuscripts fit into art collections is one that has yet to be satisfactorily answered. In museums lacking a distinct manuscript department, manuscripts can sometimes be found in the Prints and Drawings Department, or they may be classified with Decorative Arts (often because of their bindings). Occasionally they wind up in the European Painting department. Because they are by definition books, manuscripts and manuscript leaves don’t always fit into standard museum classification systems. The same goes for museum cataloguing databases, which are usually designed for works of art that require minimal metadata (title, artist, date, place of origin, exterior measurements). As paleographers and codicologists, we want more than the standard museum database can provide: number of lines per page, measurements of the writing space, a collation, a full description of the binding, and so on. Although the Ege provenance of the Albright-Knox leaves is extremely important, the database does not have room for that piece of information; I only know it because I recognize the leaves. Obviously museums with just a few leaves or codices can’t be expected to design their entire database structure around those few items, but it is an issue for users to keep in mind when searching for manuscripts hiding in art collections.

Before you leave the area, don’t forget to visit nearby Niagara Falls. If you remembered your passport, we can take a quick trip to see the view from the Canadian side before turning south for Pennsylvania.

Before you leave the area, don’t forget to visit nearby Niagara Falls. If you remembered your passport, we can take a quick trip to see the view from the Canadian side before turning south for Pennsylvania.