As we leave Colorado, we’ll take I-70 due west over the Rockies. Once we come through the mountains into Utah, we’ll turn north on I-15 and head for Salt Lake City where we will visit the Utah Museum of Fine Arts. At UMFA, a search in the collection database for “parchment” yields eight records, five of which include images (one of the five is printed, not handwritten, although it is illuminated by hand). One of these may look familiar to you by now, since we have encountered it in several other collections over the course of our cross-country journey: a leaf from a manuscript I have come to call the St. Alexius Hours:

If you remember, we spotted another leaf from this manuscript back in Iowa, at which time I provided links to several other leaves from this manuscript and posted an image of the leaf belonging to the Boston Public Library. Every known leaf has this full floriate border of rinceaux with acanthus, birds and flowers, with a medallion on every page illustrating a scene from the life of St. Katherine or St. Alexius. It would be well worth the effort to digitally reconstruct this manuscript in order to watch the narrative sequence of the miniatures unfold.

Also on the UMFA site is a very thorough lesson plan for teaching students about medieval manuscripts, each lesson focusing on a different UMFA leaf. This is a great model of how leaves can be used in K-12 education.

Before we leaves Salt Lake City, we’ll stop at the University of Utah to see their twelve leaves, including a leaf from a collection of Decretals and a selection of eleven Ege leaves. These haven’t been digitized, so it isn’t possible to identify them with certainty, but once they’re imaged it should be fairly straightforward to associate these leaves with known Ege manuscripts.

Now we’ll continue north out of Salt Lake City (stopping to admire the eponymous body of water on the way out of town), making our way to Utah State University in Logan.

Utah State University is home to several codices and leaves, among them a truly spectacular Book of Hours that has been completely digitized here. The manuscript is known as The De Villers Hours because the last few leaves include genealogical annotations made by members of that family in the early seventeenth century. The De Villers (also spelled De Villiers) were wealthy members of the French bourgeoisie who lived in the Dijon region of Burgundy. The manuscript – a Book of Hours dating from the late fifteenth century – may have been made for a member of the family. Although the liturgy reflects the generic Use of Rome, the calendar gives particular emphasis to Burgundian saints such as Philibert (20 August) and Benignus (24 November), both of whose names are written in gold leaf.

The annotations at the end of the manuscript focus on Pierre De Villers and his wife Jehanne Chisseret, married in 1603 at the Church of Mary Magdalene (city unspecified, but presumably the Cathedral of the Magdalene at nearby Vézelay). The births and baptisms of their children follow, including this rather poignant entry on p. 180 (in the citations below, I will refer to the manuscript using the pagination given in the digital facsimile):

“Le troisiesme jour du mois d’Aoust mil six cent et quinz ladit demoiselle Chisseret se delivra au sixiesme mois de sa grossesse d’une fille qui eust baptesme auquel on donna le nom de Perrette et ne vesquit que quatre ou cinq heures…” (“On the third day of the month of August in the year one thousand six hundred and fifteen, the aforementioned lady Chisseret in the sixth month of her pregnancy was delivered of a daughter who was baptized and to whom the name Perrette was given, and she only lived for four or five hours.”)

Office of the Dead, De Villers Hours, p. 126 (Utah State University, Merrill-Cazier Special Collections & Archives, Vault Book 360) (photo courtesy of USU)

The De Villers Hours is a beauty, heavily illustrated with six full-page and nineteen quarter-page miniatures, some of which preserve a complex, sophisticated and unusual iconographic programme. The Office of the Dead is particularly noteworthy, opening with a rich and detailed depiction of The Three Living and the Three Dead (shown at left).

Above the text, which is written on a trompe-l’eoil sheet with curled edges, the Three Dead emerge from their graves to confront the Three Living, one of whom tumbles from his horse in terror. Below the text, Job reclines on the dung heap, taunted by his so-called friends. Both images are often found illustrating the Office of the Dead, the former for obvious reasons, the latter as a metaphorical representation of abject humility. This is not the only illustration in this section of the manuscript, however. There is a small miniature at the beginning of each nocturn (i.e. each of three sections) of Matins.

The first nocturn of the Office of the Dead begins on p. 132 and is illustrated by a very rare depiction of St. Jerome. Usually, St. Jerome (the translator of the Bible into Latin) is depicted as a Cardinal dressed in luxurious vestments, seated in his study accompanied by his attribute of a lion. There is a reason Jerome is accompanied by a lion in medieval art; the story goes that once when he was meditating in the desert, he removed a thorn from the paw of a lion and was granted a vision of the Crucifixion. This is the scene depicted in the De Villers Hours:

Jerome, barefoot and dressed in rags, kneels in the wilderness gazing at the vision of Christ Crucified above a linen-draped altar. A lion crouches before the altar, a long thorn protruding from its bloody paw. The scene is tightly composed and beautifully rendered, with a deep background culminating in the silhouette of a towering hilltop city (somewhat reminiscent of the Burgundian town of Vézelay as seen from afar, with its romanesque church of Mary Magdalene at the summit). One does have to wonder, however, if the artist had ever seen an actual lion.

The other two nocturns are illustrated by additional scenes of Job on the dungheap: at the second nocturn (p. 140), he gazes up as his wife empties a slop-bucket on his head; at the third (p. 150), she simply berates him. All three scenes are quite rare, and I have never before seen a Book of Hours with illustrations at the beginning of each nocturn of the Office of the Dead. In fact, in the 1996 Masters Thesis by Kevin R. Williams that accompanies the manuscript, the author argues that this may be one of the earliest such depictions of Jerome in a French context (Williams, p. 42).

Unfortunately, nothing is known of the manuscript’s whereabouts between the seventeenth century and 1953, when it was given to Utah State University by L. Boyd and Anne McQuarrie Hatch, art collectors of some stature in mid-century Manhattan and Utah. The manuscript was part of a large and important gift of rare books and antique furniture. Mrs. Hatch was particularly interested in reconstructing the rooms in which the art and furniture she collected were originally displayed; one of these rooms is part of USU’s rare book library (see also this 1952 article). The manuscript does not appear to have ever been on the market – at least, I can find no trace of it in the Schoenberg Database. The Hatches are assumed to have purchased the manuscript from a private dealer during one of their European sojourns. For those of you keeping track at home, the manuscript is a Book of Hours (Use of Rome), N. France, ca. 1480-90, with 95 + ii leaves, nineteen small miniatures, six full-page miniatures, 21 lines-per-page, approx. 21 x 16 cm.

[And now, a codicological side note for those who care about such things; if you aren’t interested, you can st0p reading and head on over to Nevada]

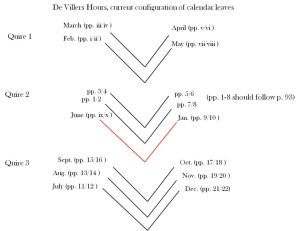

If you look carefully at the digital facsimile, you will notice that there is something odd about the first sixteen leaves of the manuscript (here called pp. i-x and 1-22). The leaves present the following texts:

pp. i-x: calendar pages for February – June

pp. 1-8: the end of Vespers and all of Compline of the Hours of the Virgin (leaves that should follow p. 93)

pp. 9-22: calendar pages for January and July – December

There isn’t a collation statement for the manuscript anywhere, but since I really can’t stand to leave a codicological puzzle unsolved, I’ve been thinking about it this week, and I think I’ve figured out what’s going on. Without studying the manuscript in person, however, this is all conjecture:

In many Books of Hours, the calendar is comprised of two quires of three nested bifolia, i.e. twelve leaves. Presumably this was originally the case with the De Villers Hours. If true, then January and June would have been conjoint:

If the Jan./June bifolium had been inverted such that January swung around to follow June, and the four leaves (presumably two bifolia) from Vespers/Compline were then interpolated between June and January, the current configuration would result:

I have absolutely no idea why the leaves were misbound. The manuscript is currently bound in late-fifteenth- or early-sixteenth-century blindstamped calf over wooden boards. The covers show evidence of modern rebacking or at least hinge repairs, suggesting that the misplacement of bifolia may have occurred during the course of the repair (presumably the same repair during which the modern paper flyleaves were added). At any rate, if we digitally put the leaves back where they belong (preceding the Hours of the Holy Cross), we find at least some evidence of the original configuration in the following reconstructed opening, in which the current p. 8 faces the current p. 94:

The red arrows point out what appear to be small round (and very old) grease-stains in the margin of both pages. When the book was closed, the stains would have met up perfectly.

I’d love to know if my conjectured collation is right…if anyone at Utah State wants to take a look at the manuscript and let me know, I would be most grateful! In the meantime, let’s keep going west. See you in 2014!

2016 UPDATE: Students of Utah State professor Alexa Sand have just created a website devoted to the De Villers Hours and another manuscript in the collection. Check out their excellent work here: http://exhibits.usu.edu/exhibits/show/books-of-devotion–a-tour-of-t