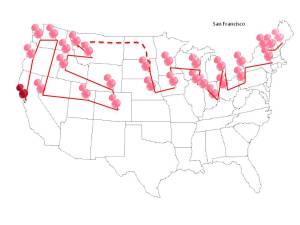

For the last few weeks, we’ve been making our way through states with relatively few medieval manuscripts. California is a different story entirely. At last count, there were more than 8,500 pre-1600 manuscripts in 47 collections in the state of California. So this may take a few weeks!

Let’s start in the San Francisco area, at the University of California at Berkeley. UC Berkeley is home to Digital Scriptorium, the digital repository for 25,000 images from 6,500 manuscripts in 31 U. S. collections. The metadata is stored in an XML platform specifically designed to address the challenges of creating electronic records for unique handwritten materials (for example, the DS platform handles composite manuscripts much more elegantly than MARC). The collection is growing, and the project, free to users but supported by membership fees from contributing institutions, is a model of self-sustainability. Note to cataloguers (the rest of you should skip to the next paragraph): working with MARC cataloguers at Yale, DS has now established a template for MARC records that will cross-walk into the DS XML format, allowing institutions to export their OPAC records to DS with minimal rekeying. This is big news, people.

Let’s start in the San Francisco area, at the University of California at Berkeley. UC Berkeley is home to Digital Scriptorium, the digital repository for 25,000 images from 6,500 manuscripts in 31 U. S. collections. The metadata is stored in an XML platform specifically designed to address the challenges of creating electronic records for unique handwritten materials (for example, the DS platform handles composite manuscripts much more elegantly than MARC). The collection is growing, and the project, free to users but supported by membership fees from contributing institutions, is a model of self-sustainability. Note to cataloguers (the rest of you should skip to the next paragraph): working with MARC cataloguers at Yale, DS has now established a template for MARC records that will cross-walk into the DS XML format, allowing institutions to export their OPAC records to DS with minimal rekeying. This is big news, people.

David admiring Bathsheba’s bare calves (somehow I think the Spanish Forger would have handled this moment differently) (UC Berkeley, Bancroft MS 131, f. 141)

But back to the manuscripts. The Bancroft Library at Berkeley counts around 300 codices and hundreds of leaves among its collection, most of which have been catalogued and at least partially digitized through Digital Scriptorium. There are so many fantastic manuscripts at Berkeley that I can’t possibly survey them here; I encourage you to explore Digital Scriptorium on your own. Many of the manuscripts have an esteemed provenance. I’m particularly interested in two in particular, because they come from the Romanesque Italian monastery at Morimundo:

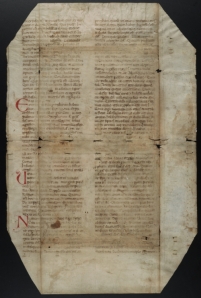

The first image (below) is of a scribal colphon, in which the scribe asks for the prayers of the reader and promises in return to “defend” the reader before God (“Omnes valete et pro me scriptore rogate/ Ut me vobiscum dominus defensare dignetur”). This is followed by a rare inscription dated 1298 that gives the name of the commissioner of the manuscript (Beltramus de Redoldi) and places the creation of the manuscript in the abbey of Morimundo. It is quite rare to have the details laid out so clearly in a thirteenth-century manuscript.

The second manuscript, at right, dates from the twelfth century. It is a compilation of several texts, the first of which is Hugh of Fouilloy’s De claustro animae. In the late twelfth-century, the monks of Morimundo recorded a list of books in their library at the end of a manuscript that now belongs to the Houghton Library at Harvard (pf MS Typ 223, f. 227v):

Bancroft MS 6 is the 44th volume on the list, tucked between Bernard of Clairvaux and Isidore of Seville and titled “De materiali claustro” (detail).

Remarkably, many of the manuscripts on the list can actually be identified with extant codices (for more on the Morimundo catalogue, see Mirella Ferrari, “Sui ‘Salmi’ e sui ‘Profeti’: dal primo catalogo di Morimondo alla Biblioteca Braidense,” in Studi di Storia dell’arte in onore di Maria Luisa Gatti Perer, ed. Marco Rossi and Alessandro Rovetta (Milan, 1999), pp. 33-46).

Speaking of provenance, it’s high time we met the most obsessive and prolific manuscript collector of all time. Sir Thomas Phillipps (1792-1872) was a compulsive collector, to put it mildly. He was notorious for buying up entire lots himself, and while he was knowledgeable about parts of his collection, when you look at the big picture it does seem as though he may have been more interested in the number of books in his collection at his Middle Hill estate than in their content. At the time of his death, he owned more than 60,000 manuscripts; it took his estate more than 70 years to sell the collection in a series of Sotheby’s auctions. There are dozens of Phillipps manuscripts in US collections, including twenty-five at UC Berkeley alone. They’re easily recognizeable by the Middle Hill ex libris stamp and the distinctively written shelfmarks.

The Oxford Dictionary of Biography gives a nice summary of Phillipps’ life, although the ultimate reference for the collection is the five-volume work by A. N. L. Munby, Phillipps Studies (1951-60).

Other collections in the San Francisco area include the De Bellis Collection at San Francisco State University (mostly documentary); the Sutro Collection at the State Library of California; and the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco (a few leaves and cuttings).

Before we leave the Bay area completely and head south down the coast, we’ll make a stop in Palo Alto at Stanford University.

Stanford has digitized several hundred fragments and some leaves of codices in their collection here. Many of these are binding fragments and show interesting signs of use and wear, such as this late-twelfth century leaf from a Bible (preserving part of II Kings). These leaves have much to teach us about medieval binding techniques. For example, it’s fairly obvious how this leaf (below) was cut and folded to create a book cover.

Some leaves require a slightly deeper dive into material evidence to sort out their re-use, like this mid-twelfth-century Austrian antiphonal (below). Those of you who have known me for a while may know that twelfth-century Austrian liturgical manuscripts are a particular interest of mine, so this fragment caught my attention.

First let’s look at the leaf itself. Although it is catalogued as a breviary (a priest’s book for the daily Offices), it is actually an antiphonal (also an Office book, but for the use of the choir, not the priest). It preserves only musical chants, using the interlinear neumatic notation typical of Romanesque Austria. The notations in the left margin are “tonary letters,” a system also used in Romanesque Austria that essentially tells the choir in what key each piece was to be sung (there’s a much more complicated musicological explanation, but this will do for our purposes). The text is of some interest as it preserves the liturgy for Trinity Sunday, i.e. the Sunday after Pentecost, a feast that was not officially sanctioned by the Catholic Church until the papacy of John XXII (1316-34). Finally, the initial [G] (for “Gloria tibi trinitas”) is a typical Romanesque Austrian “white-vine” style, with the characteristic closed buds at the end of the vines and decorative bands squeezing the body of the letter.

The leaf was cut to the size of a smaller book (probably in the fourteenth or fifteenth century) to be used as a free flyleaf at the front or back. If there had been paste damage on the other side, I would have concluded that the leaf had been a paste-down inside the cover, but the other side is just as clean as this, indicating that it was a free flyleaf. The tab partially preserved along the bottom edge is where the flyleaf was sewn into the book, with the tab protruding after the first gathering. The triangular notch was a sewing hole. Finally, small brown dots in each corner are rust marks left by decorative bosses nailed to the cover of the book. At some point, the leaf was removed from the binding as a recognized collectible in its own right; Stanford bought it from dealer Bernard Quaritch in 2010.

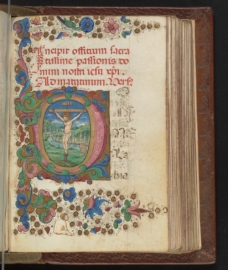

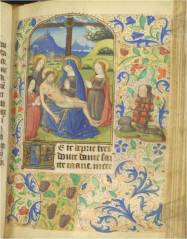

Lest you think that Stanford’s collection is all cut-up binding fragments, I will leave you with this beauty, a late-fifteenth-century Florentine Book of Hours.

Next week, we’ll virtually visit one of my favorite places to watch the sun set over the Pacific, visit old friends in the Impressionist Gallery and admire one of the greatest manuscript collections in the country: the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles.

p.s. there was an article in the Boston Globe yesterday about my blog, with a photo gallery here. My thanks to reporter Kathy Burge and photographer Lane Turner, as well as to the curators who kindly gave us permission to reproduce images from their manuscripts.

![Detail: King David inhabiting an initial [B] for "Beatus vir" (Psalm 1)](https://manuscriptroadtrip.files.wordpress.com/2014/01/random-page.jpg?w=225&h=300)