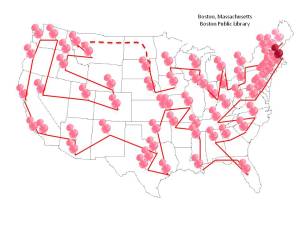

This week, after eighteen months, forty-nine posts, and forty-eight states, the Manuscript Road Trip goes home. Welcome to Boston!

I’ve lived just west of Boston for fifteen years, much of that time spent working as a consultant cataloguing collections of medieval manuscripts in the area. Ironically, some of the collections I know so well are not particularly well-known outside New England. This will change in the fall of 2016 with the opening of “Pages from the Past,” a major exhibition of several hundred manuscripts from more than a dozen Boston-area collections, an exhibit I have the great privilege of co-curating with Jeffrey Hamburger, William Stoneman, Nancy Netzer, and Anne-Marie Eze. As the exhibit is still eighteen months away, I’m going to spend the next few weeks writing about collections in the Boston area. Let’s start with one of the great treasures of the City of Boston: The Boston Public Library.

Let’s start with one of the great treasures of the City of Boston: The Boston Public Library.

The Boston Public Library, founded in 1854, was the first municipal “Free Library” in the United States. In the 1880s, architect Charles McKim was commissioned to design a worthy home for the Library, and the result is an architectural gem.

The Boston Public Library, founded in 1854, was the first municipal “Free Library” in the United States. In the 1880s, architect Charles McKim was commissioned to design a worthy home for the Library, and the result is an architectural gem. With its palazzo-style courtyard and famed murals by John Singer Sargent, the Central Branch at Copley Square is one of the premier examples of Renaissance-revival Beaux Arts design. Lest the grand and imposing edifice intimidate the public it was designed to serve, the simple phrase “FREE TO ALL” in granite relief above the arched doorways serves as a constant reminder of the Library’s mission and mandate.

With its palazzo-style courtyard and famed murals by John Singer Sargent, the Central Branch at Copley Square is one of the premier examples of Renaissance-revival Beaux Arts design. Lest the grand and imposing edifice intimidate the public it was designed to serve, the simple phrase “FREE TO ALL” in granite relief above the arched doorways serves as a constant reminder of the Library’s mission and mandate.

That mission includes the stewardship of several extremely important special collections, primarily Americana (John Adams’ personal library, for example, as well as early American and Civil War collections and the Sacco and Vanzetti Defense archive). Unbeknownst to most library patrons, the Boston Public Library is also home to several hundred medieval and Renaissance manuscripts.

One of the BPL’s first medieval acquisitions, MS f. Med. 5 (f. 103, Easter Sunday, with an historiated initial lacking)

In 1878, the Boston Public Library bought its first medieval manuscripts, two volumes of a multi-volume set of Nicholas of Lyra’s Postilla super totam bibliam written in “Paradisus” abbey, Germany (poss. Düren) in 1471. The two manuscripts preserve Proverbs, Ecclesiastes and the Song of Songs (MS f. Med. 3), and the Twelve Minor Prophets (MS f. Med. 4); two other volumes of the set are Harvard University, Houghton Library MS Lat. 231 (which contains the Book of Wisom and is consecutive with f. Med. 3) and Philadelphia, Free Library, Lewis E 43 (Pauline Epistles). Another early acquisition was MS f. Med. 5, a mid-fourteenth-century Missal from Italy given to the BPL by Dr. W. N. Bullard in 1896.

It was not until 1900, however, when Librarian James Lyman Whitney entered into a long-standing relationship with British bibliophile Sydney Cockerell, that the collection began to truly take shape. William Stoneman, Curator of Manuscripts at Harvard University’s Houghton Library, traces the early roots of the BPL’s manuscript collection to the 1849 sale of 702 manuscripts from the library of French collector Joseph Barrois (1785? – 1855) to the Fourth Earl of Ashburnham (1797 – 1878), described by Seymour de Ricci as “one of the great collectors of the nineteenth century” (Stoneman, p. 350).

Notes made by Sydney Cockerell inside the front cover of BPL MS q. Med. 6, a late thirteenth-century Psalter

It may seem a distant connection, but when the Barrois-Ashburnham collection was sold at Sotheby’s on 10 June 1901, Sydney Cockerell bought twenty-one manuscripts on behalf of the Boston Public Library. He had been authorized to do so the previous year by the Librarian and Trustees, who granted him free reign to spend the significant sum of $1000 “for the purchase of illuminated manuscripts.” (see W. P. Stoneman, “‘Variously Employed’: The Pre-Fitzwilliam Career of Sydney Carlyle Cockerell” in S. Panayotova, ed., Art, Academia and the Trade: Sir Sydney Cockerell (1867 – 1962) (Cambridge Bibliographical Society, 2010), pp. 345-361, at pp. 350-351).

Cockerell’s knowledge of the art market made him the perfect agent for the Library, and his choices were savvy. Broadly interpreting the Trustees’ instruction to purchase “illuminated manuscripts,” Cockerell acquired a variety of codices at the Ashburnham sale, for the most part decorated but unillustrated, focusing on multiple genres, scripts, and time periods rather than bidding on pricier (and therefore fewer) books that might have been more sumptuous. There were notable exceptions, of course. Over the course of their relationship, Cockerell acquired twenty-six manuscripts for the Boston Public Library, some of which were indeed quite beautifully illuminated. He facilitated the acquisition of one of BPL’s finest books, a copy of St. Augustine’s De civitate dei written in Utrecht in 1466 and illuminated by the eponymous “Master of the Boston City of God,” since identified as Antonis Rogiersz uten Broec (BPL MS f. Med. 10). Over the last century, the collection has been augmented by gifts, bequests, and purchases and is now one of the largest municipal manuscript collections in the country.

Individual manuscripts in the collection have been studied over the years, and some are well-known to scholarship. Until recently, however, there was no catalogue of BPL manuscripts other than the incomplete listing in the de Ricci Census and its Supplement. I recently spent two years writing a comprehensive catalogue of the collection, and MARC records based on my work are currently in development that will include links to my formal descriptions. A large-scale digitization project is also underway, although some of the manuscripts had been previously digitized and are available online through the Internet Archive:

BPL q. Med. 20 (Marcus Manilius, Astronomica, Italy (Ferrara), 1461)

BPL pf. Med. 97, f 1 (oversize Ferial Psalter, Piacenza, ca. 1495). This massive choirbook was originally part of a set of fourteen giant manuscripts produced for the Abbey of St. Sixtus in Piacenza.

BPL f. Med. 73 (Johannes Andreae, Hieronymianus, Netherlands (Utrecht), ca. 1470)

BPL f. Med. 91 (Guillaume de Tignonville, Dits des philosophes, France, ca. 1420)

BPL f. Med. 101 (Christine de Pizan, Le livre des trois vertus, France, ca. 1450)

BPL f. Med. 125 (Gregorio Dati, La Sfera, Italy (Pesaro), 1484)

BPL q. Med. 129 ([Hours of the Passion, in verse], Flanders, ca. 1465-1475)

BPL f. Med. 133 (Das Leiden unserz Herren Jhesu Christi, Germany, ca. 1460)

Here are a few other highlights of the collection.

MS f. Med. 95 is a homiliary thought to have been written in the early part of the tenth century at the Benedictine abbey of St. Allyre in Clermont, France. It may be the earliest complete codex in New England (for those who care about such things, this was Phillipps Manuscript 13842).

MS f. Med. 84 is a sumptuous mid-thirteenth-century Psalter from Flanders that begins with a calendar, seven full-page miniatures (a standard cycle illustrating the life of Christ), and a full-page historiated initial. Each page of the calendar includes a charming framed illustration of the Labor of the Month, for example Janus feasting in January and a peasant slaughtering a pig in December.

The full-page miniatures are beautifully executed and heavily gilt:

King David playing the harp (above) and defeating Goliath (below), inhabiting the letter B (for “Beatus vir,” the beginning of Psalm 1) (BPL MS f. Med. 84, f. 14v)

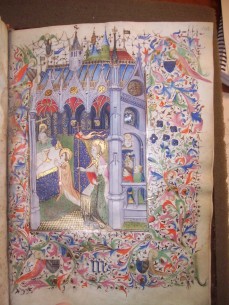

Another stunner is MS q. Med. 81, known as “The Québriac Hours” for the family that owned it for some time. The manuscript was written and illustrated in Brittany around the year 1420 and includes two dozen miniatures. The patron of the manuscript, a woman in a green gown and fashionable howve headpiece, makes an appearance in two of them:

One the later treasures of the collection is a set of fourteen full-page miniatures by the great Simon Bening (1483-1561), taken from a Spanish Rosary Psalter in all likelihood commissioned for Joan I (“the Mad”) of Castile around the year 1525. The miniatures, collectively BPL MS pb. Med. 35, have been published in facsimile.

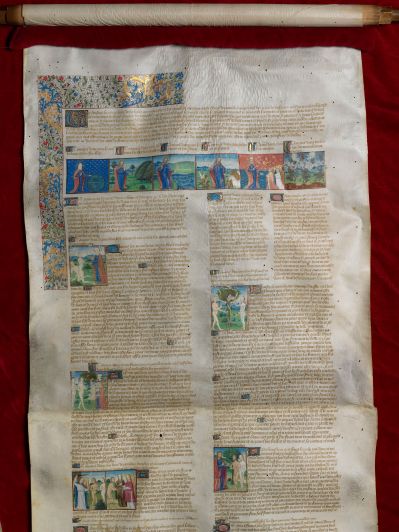

I leave you with BPL MS pb. Med. 32, a beautifully illuminated manuscript of the French scroll chronicle I have christened La Chronique Anonyme Universelle, the subject of my forthcoming book. The 34-foot-long scroll was written in eastern France in the 1470s. Nothing is known of its early history until it was offered as lot 626 in the Barrois-Ashburnham sale of 1901, when it was acquired for the Library by Sydney Cockerell (Ashburnham actually owned two copies of the Chronique; the second, lot 627, is currently in private hands). The Chronique tells the story of mankind from Creation to the Middle Ages, illustrated by fifty-eight miniatures. Originally, the BPL copy would have concluded during the reign of the French King Louis XI, but it is lacking several sheets and ends imperfectly at Pope Urban VI (d. 1378), Holy Roman Emperor Henry II (r. 1014 – 1024 C.E.), the French King Philip IV (Philip the Fair) (r. 1285 – 1314 C.E.), the English King Henry III (r. 1216-1272) and Godfrey of Bouillon.

The text is formatted in parallel columns, beginning with Biblical and ancient history before eventually settling into a four-column format recording a Papal chronicle, the history of the Roman and Holy Roman empires, and the development of the kingdoms of France and England, with a brief detour into the Crusades. The intercolumnar spaces are filled with detailed and complex genealogical diagrams that trace the direct descent of the royal houses of Europe from Adam by way of Aeneas of Troy. En route from Genesis to medieval Europe, the narrative stops to tell the tales of such luminaries as Queen Esther, King Lear, King Arthur, and Joan of Arc (although the section that would have included The Maid of Orléans is lacking in this copy). The BPL scroll is among the finest of the 28 known copies and was likely produced for French nobility. The earliest manuscript of the Chronique was compiled around 1415, in the context of the Hundred Years War. This French world chronicle is therefore inherently Francophilic at the expense of the English, serving to re-enforce its intended audience’s sense of entitlement and inherent nobility while at the same time making the English out to be war-mongering charlatans.

A few details:

The scroll is one of the highlights of the collection, and for good reason. It appears that when the Trustees of the Boston Public Library charged Sydney Cockerell with buying “illuminated manuscripts,” he occasionally took them at their word.

Next time, we will visit one of my favorite Boston sites, the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum.