Last week, the Annual Meeting of the Medieval Academy of America (the learned society of which I am Executive Director) took place at the University of Notre Dame in South Bend, Indiana. It was a delightful, congenial, and edifying gathering of more than three hundred medievalists who spent three days learning from one another, viewing exhibits and performances on campus, and generally enjoying each other’s company. After the conference, I had the great pleasure of taking an actual manuscript road trip to Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana, about two hours south of Notre Dame. I had been invited to lead a workshop and deliver a lecture about some recent discoveries concerning manuscripts and fragments in their collection. Seems like a great time for a blogpost!

Like most midwestern U.S. collections, Purdue has only a handful of pre-1600 manuscripts of European origin, most of them fragments. But if I’ve learned anything in the decade since I started this blog, it’s that every manuscript has a story to tell, if we know how to listen.

Mr. Bragge Buys a Manuscript

We’ll start with MSP 164, a fifteenth-century codex from Germany that preserves Gregory the Great’s Homilies on the Book of Ezechiel, followed by a subject index. The manuscript includes two skillful miniatures: on folio 1r, Pope Gregory sits at a medieval writing desk copying an exemplar, wearing his papal regalia; on f. 51 recto, a second miniature depicts the unidentified Man in white linen of Ezekiel’s visions measuring the Temple, as in chap. 42, verse 15. The color scheme, the style of the initials, and the heavy outlines – almost like a woodcut – are typical for German manuscripts of this period.

The style of the script and decoration certainly place the codex in the mid-15th century, but there is more evidence in the manuscript that narrows it down even further. In red colophons on ff. 98r and 106r, the scribe has actually told us precisely when he completed the manuscript and where! On f. 98r, he notes that he was writing at Huysburg Abbey (in Germany, near Halberstadt) under the abbacy of Theoderic, who was abbot from 1448-1483. But on f. 106r, we get an even more specific date: “Anno incarnationis dominicae Millesimoquadringentesimosexagesimosexto” (seriously, that’s how he wrote it): i.e. the year 1466. That was easy!

We’ve learned several things from this initial examination: the manuscript was made for a community of Benedictines in Huysburg, Germany, in 1466, and was provided with a handy subject index to use when composing sermons. Slightly later marginal notes indicate that it was used in this way for decades. But what happened next? Incredibly, Huysburg was one of the few German monasteries that survived the Reformation. The abbey was suppressed in 1804 during the secularization in Prussia, when its buildings and estates passed to the State and its library was dispersed.

To find out what happened after the dispersal of the library, we need to head to the internet, in particular to the Schoenberg Database of Manuscripts, a resource administered by the Schoenberg Institute for Manuscript Studies at the University of Pennsylvania. The Schoenberg Database is a provenance database in which each record represents a transaction involving a single manuscript. There are currently nearly 264,000 records in the database, representing sales, gifts, and recorded observations of tens of thousands of individual manuscripts over hundreds of years. Sales of the same manuscript can be linked together in the database, providing a trail of ownership. If we search for sales of manuscripts of Gregory’s Homilies on Ezechiel associated with the Abbey in Huysburg, we find three linked records that seem to represent sales of this very manuscript: Covent Garden bookseller Joseph Lilly in 1863, Sotheby’s London in 1876, and Sotheby’s London again, in 2014.

The 1876 sale (at left) is identified only as the collection of a “Gentleman of Consummate Taste and Judgment” (as the catalogue eloquently put it); this elegant gentleman was collector William Bragge, a civil engineer who traveled the world for his work on railways and other projects. As an antiquarian, he was particularly interested in the history of tobacco, but he also took advantage of his travels to build an important collection of rare books and manuscripts, much of which was deaccessioned at this 1876 Sotheby’s sale.

There are several more pieces of evidence to consider, two modern pencil inscriptions on the first flyleaf that help fill in the period between the Bragge sale in 1876 and Sotheby’s in 2014. The inscriptions are faded and difficult to read, but thanks to some post-processing by University of Oklahoma professor William Endres (thanks, Bill!), the lower inscription – at least – can be read: it was written in Philadelphia, on Christmas Day 1905, signed “A.S.R.”

A.S.R. in Philadelphia in 1905 is almost certainly antiquarian book dealer Abraham Simon Wolf Rosenbach, who died in 1952, although the inscription is not in his hand. The inscription on the right is more challenging, and may require imaging under ultraviolet light to discern completely. I’ve got “Reverendae Matris”…something…”Maria Louis”…something…and maybe signed “Edmond Philips,” although I’m not totally certain about that bit. At the very least, we know that the manuscript was in Philadelphia by 1905.

Finally, here’s why it’s always valuable to see the actual object rather than relying solely on digital imagery. On that same leaf, in the lower right corner, is an embossed ownership stamp that is not legible under direct white light (left). Using raked light (coming in at a 90 degree angle, that is), I was able to read it (right). I’m fairly certain that it says “Ursuline Academy.” The Ursulines are communities of Catholic nuns, and there are multiple Ursuline Academies around North America. I don’t know – yet – which Ursuline Academy once owned this manuscript, but I hope to figure it out eventually.

As I hope I’ve demonstrated, a whole codex like this one accretes significant amounts of evidence over its lengthy life span that we can use to reconstruct its journey from there and then to here and now. Unfortunately, most medieval manuscripts don’t survive intact.

A Stowaway!

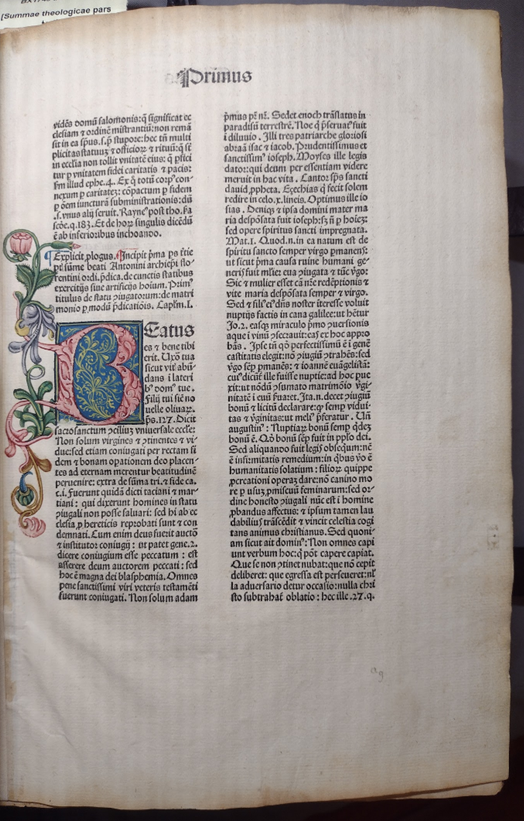

For an example of this, we’ll take a look at an early printed book, the Summae theologicae of St. Antoninus, Archibishop of Florence, who died in 1459. This theological work was published by Venetian printer Nicolas Jenson in 1477. It’s lovely, clean and bright, with delightful handcolored woodcut initials throughout, in a contemporary chained binding. But we’re not here to talk about early printed books. Why, then, are we looking at this? Because it contains a stowaway: inside the front and back covers are fragments from an earlier manuscript.

In the fifteenth-century, this binder needed pieces of parchment to secure the leather turnins, and a pile of old manuscripts was just the thing. In all likelihood, this manuscript was falling apart in the 1470s or had been superceded by a printed book or more up-to-date manuscript, so the codex was dismantelled to be recycled as part of the binding. This early-modern recycling was extremely common, and it’s why I always recommend that librarians survey their early bindings to see if they happen to have bonus fragments that they might not have known about. These leaves come from an early 11th-century copy of Haimo of Halberstadt’s homilies. The leaf in front is Haimo’s Homily 18, for the 2nd Sunday after Epiphany, and the one in back is from his Homily 15, for Epiphany itself.

Like this manuscript, which may very well be the oldest European manuscript at Purdue, untold thousands of codices have been lost due to fire, flood, war, and other dangers, early-modern recycling, or the knife of the biblioclast. In early 20th century America in particular, as readers of this blog will know well, dealers were in the habit of cutting up manuscripts to sell leaf by leaf, at a significant profit. By asking a different set of questions, we may be able to determine how and when a leaf was separated from its sister leaves, search for more leaves from the same manuscript, and even work to digitally remediate the destruction of biblioclasm in a virtual space.

A Tiny Little World Traveler

Let’s start with f. 9 in the fragment collection MSP 136, a tiny little manuscript page. When I say tiny, I mean TINY. It’s only 3.5 x 4.3 inches, about the size of a standard index card. That is extremely small for a medieval manuscript, and tells us something important right away: by contrast to the codex of Ezechiel homilies, which was designed to be read from a lectern or writing desk, this manuscript was meant to be portable. Next, we need to determine what kind of manuscript this is. From the rubrication, we can see that it contains lessons 4 through 9 of one feast and lessons 1 through 3 (and the rubric for the fourth) of the next. It also has other prayers and chant texts (but no music). That makes it a breviary, a liturgical manuscript with readings for the Divine Office for the use of the priest or other officiant. One rubric tells us even more specifically which feastday we’re looking at: Dominica quinta post epiphaniam (“Fifth Sunday after Epiphany,” in mid-February).

Next question: can we approximate where and when was it produced? The style of the script looks like 15th-century Italy to me, but it’s hard to be more specific than that with so little evidence. But the metadata in the Purdue online catalogue identifies the date of origin with surprising specificity: 1464. How could the Purdue cataloguer have known that? It certainly isn’t recorded on the leaf itself. The record continues: “We know the name of the scribe (Bartholomew) and precise day on which the manuscript was completed (December 22) from an inscription on the last folio of the once-intact book.” Interesting! But again, where did that information come from? Time to start Googling. A search for “breviary, 1464” brings us to the indispensable provenance blog by British scholar Peter Kidd, who has in fact conducted significant research on this very manuscript and explains the whole story in this 2022 blogpost.

The Purdue leaf was purchased from Dawson’s Bookshop in Los Angeles several decades ago. According to Kidd, Dawson’s acquired the whole manuscript sometime after it was sold at Sotheby’s on 29 June 1938, lot 512 (above). And here we see the source of the specific date of 1464: when whole, the manuscript had a colophon identifying the scribe not as Bartholemew but as one Karolus de Blanchis de Bardano, rector of the tiny 12th-century Church of St. Bartholomew in Cune, in the Italian diocese of Lucca. The tiny church still stands today in the village of Cune, not far from Pisa. Karolus goes so far as to record that he completed the manuscript at the 18th hour of the 22nd of December, 1464.

Next we turn to famed manuscript scholar Christopher de Hamel, who, in his work on manuscripts in New Zealand (see Bibliography below), traced the provenance of this manuscript back even further: he identifies it has having been part of the collection of William Ardene Shoults (1839–1887) of London, who bequeathed it to his widow Elizabeth. In 1888, the first Anglican Bishop of Dunedin convinced her to donate the manuscript – along with many other books and manuscripts from her husband’s collection – to help establish the library of Selwyn College in Dunedin, New Zealand, which deaccessioned and sold it at Sotheby’s in 1938. He goes on to record that the manuscript was then acquired by bookseller Marks & Co., of 84 Charing Cross Road in London, who presumably sold it to Dawson’s Bookshop in Los Angeles soon thereafter.

Here’s the final chapter of the story. Dawson’s offered the codex for sale in February of 1940 for $75, but apparently no one was interested. By April of that same year, they tried a different tactic. They dismembered the manuscript and began selling single leaves for around $1 each. With more than 300 leaves to offer, they could make a lot more money this way. Purdue purchased the leaf directly from Dawson’s, and it was Dawson’s who provided the Purdue cataloguer with the information about the date and place of origin, which of course Dawson’s knew because they had once owned the complete manuscript with the colophon. And guess what happened when they dismembered it? They separated the colophon leaf from its sisters. If the Purdue cataloguer hadn’t preserved that information, even though there was no supporting evidence on the leaf itself, the job of identifying this little wanderer would have been much more difficult. And the colophon leaf? It has disappeared, so do keep an eye out for it.

This tiny manuscript has led an extraordinary life. From Italy to London to New Zealand, back to London, to Los Angeles, then, broken and in pieces, this single leaf blowing on the winds of commerce and settling down at last in West Lafayette, Indiana. Taking into account the extra 4,000 miles you have to travel to get from London to New Zealand by boat instead of flying, that’s a total journey of nearly 42,000 miles. This leaf is a resilient little survivor.

But we’re not done yet. The last question is – can we find more leaves? Now that we have so much information, it is actually quite simple to find more. Google “breviary, Lucca, 1464” and you will find, among others, four leaves for sale right now on EBay for around $250 each.

Miss Popularity

Next up is leaf 6 of MSP 136, a lovely fourteenth-century fragment from France. Like the Lucca leaf, this leaf comes from a Breviary, in this case preserving Office liturgy for the feast of Mary Magdalene on July 22; we know this because the antiphons and the Responsory “Pectore sincero dominum Maria” can be easily identified with her liturgy using online resources like the CANTUS liturgical database. In addition, the readings include biblical quotations about her life.

When working with fragments, the measurements of the leaf and the layout of the text work together to create almost a fingerprint: if you find leaves with the same dimensions and the same number of columns and lines, you may have a match. The writing space, in particular, is a often a clear indicator that two leaves do indeed come from the same parent manuscript. The Purdue breviary leaf has 30 lines of text in two columns and measures around 7 x 4.75 inches. Using these criteria, I’ve identified leaves of this manuscript offered by New York dealer and biblioclast Philip Duschnes as early as 1939.

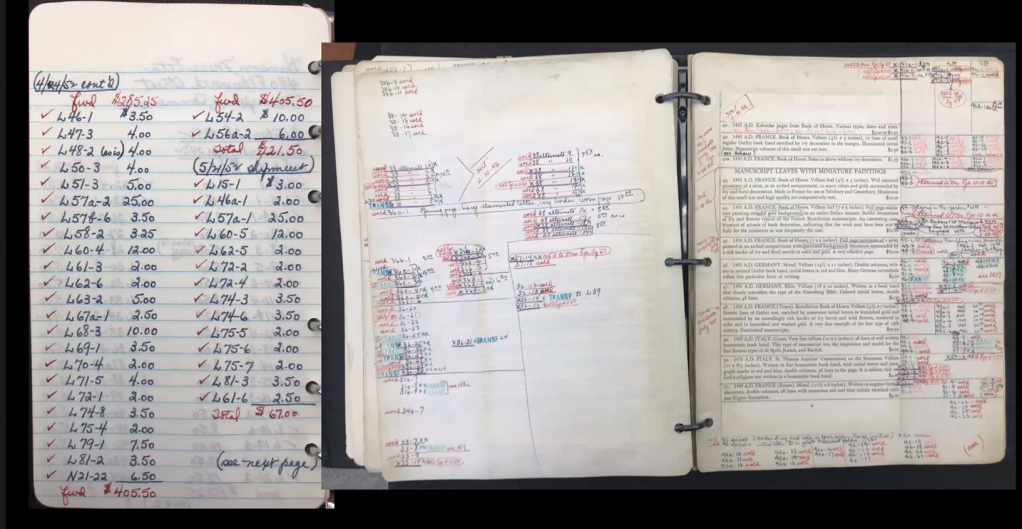

According to my research on Duschnes and his sales of manuscript leaves, he was selling leaves of this manuscript from 1939 through at least 1948, although I have not yet been able to identify when or under what circumstances the codex was dismembered. But Duschnes wasn’t the only one selling leaves of this manuscript. Duschnes counted among his friends and business associates our old friend, Cleveland bookdealer Otto F. Ege, who – again as readers of this blog will know – was among the most prolific of the twentieth-century American biblioclasts.

Because leaves of this manuscript are always no. 24 in the Ege portfolio titled Fifty Original Leaves from Medieval Manuscripts, they can be cited as Handlist 24 (referring to Scott Gwara’s handlist in the book Otto Ege’s Manuscripts). Here are some examples of Handlist 24 from the portfolios at the University of Colorado, University of Minnesota, Stony Brook University, and the University of Massachusetts, Amherst (note that these leaves are almost always misidentified as a Book of Hours rather than a Breviary, legacy data that comes from Ege himself). But Ege also sold leaves of this manuscript outside of the portfolio collections. We know this because of extensive sales ledgers recently discovered in the basement of the Lima, Ohio, Public Library by Ohio State University curator Eric Johnson (below).

Ege had a long-standing business relationship with the Lima Public Library whereby they would sell leaves on his behalf and keep 30% of the proceeds to support their Staff Loan Fund. According to the ledgers, the Library sold 133 leaves from Handlist 24 between 1935 and 1967, making this one of Ege’s most popular manuscripts. The buyers were scattered across the country from Los Angeles to Nova Scotia and from Oregon to South Carolina, in fifty-one cities across twenty-four states, including three Indianans: a Mrs. Harry George from Bedford bought one for $5 in 1937, Mrs. Ruth S. Ryan of Evansville bought two leaves in 1942, for $3.50 and $6.50 respectively – the pricier one likely had more decorated initials – and Gary’s own Sara Fenwick paid $2.50 in 1946. Do their descendants still own these leaves? Are they hanging on Ruth Ryan’s granddaughter’s living room wall or stored in a trunk in Sara Fenwick’s great-nephew’s attic? We may never know, but it’s always possible that leaves like this may appear in a roadside antique barn or online auction, so keep an eye out.

Separated at Birth

For our final case study, we’re going to combine fragmentology with codicology, the study of the materiality and structure of a manuscript, using this gorgeous oversize Bible leaf from mid-fourteenth-century England. The first thing to notice is that it is HUGE: nearly 18″ x 12”. Originally, this was likely the third of a four-volume set, with hundreds of leaves in each codex, nearly a thousand in all. That’s a lot of sheep, a lot of labor, a lot of time, and a lot of resources. This was a valuable object. It’s also very well known among those who study dismembered manuscripts (there are more of us out there than you might think!). It is known as the Bohun Bible (pronounced “Boon”) because of an early but uncertain association with the English Bohun family, who were themselves closely associated with the English royal family in the mid-fourteenth century, when this manuscript was produced.

Thanks to research by Peter Kidd and Christopher de Hamel, among others (see Bibliography below), we know quite a lot about this manuscript. Several seventeenth-century English owners signed the last page, which is currently at Oxford’s Bodleian Library. The last of these was Sir Peter Leycester (d.1678). Peter Kidd recently found a description of this manuscript in Sir Peter’s library catalogue, where the Bible is described as “Part of a greate Latine Bible in Manuscript: a fayre character with greate Gold-Letters (about the tyme of Henry VI, as I coniecture, it was writ) contayninge the Proverbs & all the Prophets.” These early collectors removed several of the pages, some with miniatures, and by 1927 the main portion of the codex had been dismembered by the London dealer Myers & Co. De Hamel and Kidd have identified several hundred leaves, including the leaf at Purdue.

This volume originally preserved a portion of the Old Testament from Proverbs to the prophet Malachi, on 413 oversize folios. Each biblical book would have begun with an elaborately decorated page like the one at the right, the beginning of the prophetic book of Nahum, which sold at Christie’s in 2015 for…wait for it…a whopping £62,500 (or around $79,000). There were twenty-two Biblical books in the manuscript, which means there were twenty-two pages like this, of which about half have been located. Many were removed by those 17th-century owners, one of whom noted the fact by leaving marginal notes lamenting the destruction such as the note on f. 410 recto (below), which reads “from the 17th verse of this 14th Chapter of Zechariah, is torne out & wantinge.”

Purdue’s leaf preserves Ecclesiasticus Chapters 39 and 40, with the beginning of Chapter 40 set off by a lovely initial. Given that each leaf has headings that identify the Book and marginal numbers identifying the chapters, putting the leaves in order would be a simple task. It is made simpler by the fact that most leaves are foliated by an early-modern hand. Some leaves are unnumbered – these are the ones that were removed early on, before the foliation was added. Purdue’s leaf is folio 107, a fact that will be important for this next exercise.

First, I need to take a moment to explain how medieval manuscripts are physically constructed. We start with an animal, generally a sheep, goat, or calf. The animal is slaughtered and skinned, the skin scraped and cleaned and soaked and stretched in a lengthy process that creates parchment, the writing surface for the manuscript. The skin is cut into rectangular pieces called “bifolia.” The number and size cut from each skin is dependent on the size of the animal and the desired dimensions of the finished book.

In the case of the Bohun Bible, each skin provided two bifolia, or four leaves, which would mean a useable surface area of 36 x 24 inches, a fairly large animal. Once trimmed, the parchment sheets are folded in half to create two attached leaves (or “bifolia”), nested in groups of four, five, or six to create small notebooks called “quires” on which the text is written. In the Bohun Bible, quires were comprised of four nested bifolia. Once the quires were ready, they were stacked in order and sewn between boards to create the finished book.

The biblioclast reverses the process…removing the quires from the binding, removing the sewing from the gutters, separating the bifolia from one another. But he doesn’t stop there – the biblioclast must parse the manuscript even further, splitting the atom and dividing the bifolium into two leaves. What I want to do today is bring two of those separated leaves back together, digitally if not haptically. If we can figure out which leaf was originally attached to, that is, conjoint with, the Purdue leaf, we can reconstruct the original bifolium, which in turn can help us to understand more about the structure of the original codex and further remediate the damage of biblioclasm.

Purdue’s leaf is folio 107. We know that f. 105 had a catchword, because that leaf is currently at the Bodleian Library. This means that f. 106 (still untraced) was the first leaf of the next quire, and f. 107, our leaf, was the second. We can now start diagramming how the quire would have been structured (below). Folio 108 is at Vassar College, and f. 109 belongs to the Free Library of Philadelphia. Folio 110 was sold in Boston in 1979 and is now untraced. We now have our first conjoint pair: the leaf in Philadelphia (the fourth leaf of the quire) must originally have been both consecutive and conjoint with the leaf sold in 1979 (the fifth leaf)! The laws of manuscript physics demand it.

Here’s where things get interesting. Remember when I mentioned that some leaves were removed before the foliation was added? When they appear, they can be situated in the correct sequence thanks to the Biblical text, although they do interfere with the niceties of sequential foliation. This leaf, recently acquired by the University of Notre Dame, has no folio number but preserves the text of Ecclesiasticus 44 and 45. It clearly belongs in our quire. It also has no catchword, so it can’t be the final leaf of the quire (that last leaf is currently untraced). That leaves us with two possible placements: leaf 6 or 7 in the quire. It can’t be the 6th, because it isn’t consecutive with the fifth leaf (the one sold in 1979). So it must be the 7th leaf. And guess what that means? The Purdue leaf and the one at the University of Notre Dame were originally a conjoint pair! That’s an amazing coincidence…these leaves haven’t seen each other in at least 100 years, and here they are today only 100 miles apart!

And now we can put Purdue and Notre Dame back together, digitally if not haptically (the leaves appear to be different colors because they were each imaged in different lighting). If we align them, we can see that the Purdue leaf has been slightly trimmed at the bottom and the Notre Dame leaf was trimmed at the right, likely for framing by previous owners.

We can even tell which part of the skin was used for this bifolium, because of the contours of the outer edge of the Purdue leaf (lower left, above). This indentation is the armpit of the animal, as it were. A leaf of the manuscript currently belonging to the Free Library of Philadelphia may even have been cut from the same skin, as the armpit contours fit together quite nicely (middle left below):

The conjoint of FLP 66.3D is untraced, so we can’t say for sure, but it seems quite likely that these three leaves were cut from the same animal skin. Centuries after the parchment was sourced, its animal origins are still discernable.

Think about what we’ve done here: using principles of codicology and the methodologies of fragmentology, we have made our way backwards from the dismembered leaves to the conjoint bifolia to the original quire all the way back to the animal itself, grazing unsuspecting on a green hill in the English countryside in the middle of the fourteenth century.

The proof, indeed, is in the parchment.

Additional Bibliography:

C. de Hamel, “The Bohun Bible Leaves,” Script & Print 32 (2008), 49-63.

P. Kidd, The McCarthy Collection, Volume II: Spanish, English, Flemish and Central European Miniatures (Ad Ilissum, 2019), no. 17 (pp. 86-90).

M. Manion, V. Vines, & C. de Hamel, Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts in New Zealand Collections (Thames & Hudson, 1989), p. 80, note 2.

very much enjoyed reading this, thank you!

Glad to hear from you!

I must admit that I am a bit jealous that you can actually get to see these manuscript! (did I already say that?)

Pingback: “The experts say.. “. Thoughts arising after reading a blogpost by Dr. Lisa Fagin Davis. – Voynich Revisionist

Pingback: Filling Blank Spaces in Medieval Manuscripts (a.k.a. On (to) Wisconsin) | Manuscript Road Trip