This week, my friend, colleague and co-author Melissa Conway has kindly agreed to serve as a guest-blogger, introducing us to the manuscripts in her care at the University of California, Riverside, which happens to be on our way from Los Angeles to Arizona. My thanks to Melissa for giving me the week off!

************************************************

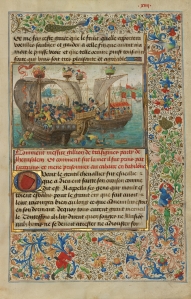

The Flight into Egypt, Walters Art Museum, MS W.188, f.112r

Since September 2013, I’ve been delighting in Lisa’s weekly blog entries, and eagerly awaiting her virtual visit to the University of California, Riverside (UCR), where I am Head of Special Collections.

Lisa and I met in 1988 as doctoral students in Yale’s Medieval Studies Department. Lisa and I hit it off from the start, bonding over our shared passion for medieval manuscripts. We took many of the same classes and paired up on research projects almost immediately. After more than twenty-five years we are still working together on manuscript-themed presentations, articles, courses and—most enduringly–on the Directory of Institutions in the United States and Canada with Pre-1600 Manuscript Holdings. Lisa has generously invited me to give a guest virtual tour of the pre-1600 manuscripts at UCR and I am honored to contribute to her outstanding blog.

Leaving the Pacific Ocean and the Getty Museum’s deluxe illuminated manuscripts behind, we travel 60 miles (97 km) eastward to reach Riverside.

Riverside is part of the “Inland Empire” or I.E., an omnibus term describing a metropolitan area that covers more than 27,000 square miles (70,000 km) and encompasses, besides Riverside, the cities of San Bernardino and Ontario and their environs. With over 300,000 inhabitants, Riverside is the most populous of the cities in the I.E. Named for its location on the (now mostly dammed up) Santa Ana River, Riverside was founded in the 1870s, fueled by the success of the navel orange, which flourished in Riverside’s citrus orchards until the post World War II housing boom transformed those orchards into housing tracts. World War II also played a role in the founding of UCR. Because returning soldiers were flooding the universities in the UC system, the UC Regents decided to establish a new campus and in 1954 UCR opened with 65 faculty and 127 students.

Rivera Library, UC Riverside

As the campus grew, the library grew with it, and rare materials were eventually given their own department. While the UCR’s flagship collection is the Eaton Collection of Science Fiction and Fantasy—the largest “SF” * collection in the world—it also has a very serviceable teaching collection of almost 80 mss– five codices, one fragment, 28 single leaves/parts of leaves, three bifolia, and 43 Elizabethan and Jacobean documents, including a land grant from 1584 with a well-preserved wax seal (shown at right).

UCR MS 6

I use the collection each quarter in a guest lecture for the History of the Book and Printing course taught by Sara Stilley, and—with sufficient advance notice– I am always happy to provide a private session to any interested group or individual.

UCR MS 10 verso

Given the popularity and survival rate of Books of Hours, it is not surprising that we have some really lovely-looking detached leaves and they are the likeliest candidates to end up on holiday cards or as illustrations on our departmental website. (UCR MS 10, at left) Since, however, Lisa has already featured so many beautiful and complete Books of Hours, I prefer to showcase instead some of our more historically interesting—if less photogenic—examples.

UCR MS 14 recto

I’d like to begin with the oldest example in the collection, UCR MS 14 (shown at right), a piece of binder’s scrap measuring only 89 by 66 mm. The spacing between the two folds is evidence of its having been re-purposed as the binding of another, later manuscript or printed volume. However deeply creased and fragmentary this scrap may be, it is a precious example of eleventh-century Caroline minuscule script—and its age alone never fails to impress. The eight lines of text on recto and verso have been identified as parts of the commentaries on Psalms XIX and XX in St. Augustine’s Enarrationes in Psalmos, which the Catholic Encyclopedia describes as masterpieces “of popular eloquence, with a swing and warmth to them which are inimitable.” (“Swing” and “warmth” are not words I usually associate with the austere Augustine.)

The next oldest example—also a piece of binder’s scrap– is a portion of Peter Lombard’s Sentences (UCR MS 15, at right).

UCR MS 15 recto

It is a decent example of the Romanesque script, most likely written in France in the last quarter of the 12th century. Both of these ancient scraps are also useful examples of the ways in which manuscripts were recycled by their thrifty medieval owners.

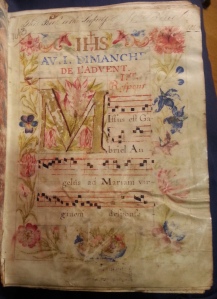

Turning our attention now to some of the intact—or nearly intact–codices—we start with an antiphonal from Germany, ca. 1500 (UCR MS 1, below). Not only is it the largest (310 x 220 cm) and heaviest of the manuscripts, but it is in a contemporary—and possibly its original–binding. It is written in a gothic script with pen-drawn versal and ribbonwork capitals, with music written in Hufnagelscrift on 5-line staves. It has one historiated initial of the three Maries at the empty tomb, and a lovely naturalistic line drawing depicting Jacob’s dream of a “ladder standing upon the earth and the top thereof touching heaven; the angels also of God ascending and descending by it.” (Gen. 28: 12, Douay-Rheims version).

UCR MS 1, illustration of Jacob’s Ladder

With its fair-faced angels and tiny dog sleeping peacefully by Jacob’s side, this illustration never fails to charm students and visitors. The startlingly green grass is a later addition, perhaps an attempt at “improving” the scene by a previous owner (or the child of that owner). One could wish this amateur artist had gone out for a long walk that day instead, but the gaudy ground covering does provide an opportunity to teach students about the various ways in which beautiful manuscripts were routinely disfigured by later owners. This manuscript was purchased for UCR in 1969 from Theodore Front Musical Literature, Inc. in Los Angeles. Based on the undated and unidentified catalogue descriptions in the curatorial file, Theodore From must have purchased it from a German dealer who has not yet been identified.

Another codex which is a particular favorite of mine is the tiny (110 x 90 mm) psalter and prayerbook, probably written in Italy in the first quarter of the 15th century (UCR MS 2, below). It is an attractive volume with an illuminated opening leaf, but it was the calendar that caught my eye because of the inclusion on 19 May of Saint Petrus de Murrone aka Pietro da Morrone aka Pope Celestine V (1215-1296). Although the Roman Catholic Church canonized Pietro in 1313, Dante Alighieri—in his Divine Comedy written at roughly the same time—placed him in the Ante-Inferno, where the shades of those who lived “without praise and without blame” are punished for all eternity. His sin was to make, “through cowardice, the great refusal” (Inferno III: 58-60) by resigning from the papacy after only five months. In doing so, he made way for the election to the papacy of Dante’s great enemy, Boniface VIII.

UCR MS 2

This manuscript is also interesting for its provenance. It bears the bookplate of the library of His Royal Highness the Duke of Sussex, Augustus Frederick (1773-1843), the sixth son of King George III. This manuscript eventually made it into the collection of another famous English bibliophile, the politician and solicitor Isaac Foot (1880-1960). A large portion of Foot’s 70,000+ collection was purchased by the UC system in 1964 and the volumes were divided among the UC campuses.

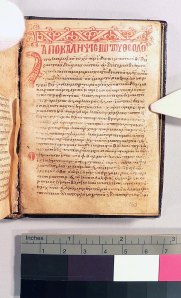

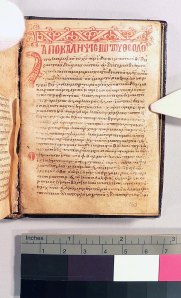

An even tinier ex-Isaac Foot codex of note is the 90 x 70 mm Greek New Testament and Apocalypse (UCR MS 4 aka Gregory-Aland 2643, below). Foot, a devout Methodist, taught himself Greek so that he could read the NT in the original language and the UCR volume is one of his 450 (!) editions of the Greek NT. The UCR volume has the distinction of being one of the 313 extant Greek manuscripts with the text of the Apocalypse, and one of only two Greek NTs that contains only the Gospels and Apocalypse; the other being in the National Library of Greece in Athens.

UCR MS 4

Not surprisingly, this manuscript is frequently consulted by biblical scholars. Dating and localizing it has been a bit tricky; although it has a colophon with the date 1289, a scholar who consulted it recently questioned this date, positing that a later scribe simply copied the colophon of an earlier manuscript.

I would love to introduce all 80 manuscripts but I have already gone over my quota, and Lisa needs to move on to the next collection on her itinerary. But before Lisa virtually leaves Riverside, I want to mention the other collection of pre-1600 leaves in Riverside–the P. Boyd Smith Hymnology Collection in the Annie Gabriel Library of the California Baptist Library. Most of these leaves are 15th century, but there is one worth stopping for—a Beneventan leaf that is in Virginia Brown’s census as a 12th century leaf from the S. N. Missale, cum neumis. It was formerly used as a cover on a manuscript, with various notarial entries on the recto.

California Baptist College, Annie Gabriel Library, P. Boyd Smith Hymnology Collectin: S. N. Missale, cum neumis (Cyriaci, Largi, Smaragdi-vig. Laurentii). Saec. XII in

According to Brown’s description, other fragments from this twelfth-century missal have been identified in Charlottesville, Leiden, London/Oslo, New York, Oberlin, Waco, and Rome (Beneventan Discoveries: Collected Manuscript Catalogues, 1978-2008 (Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 2012), p. 370, MS RVC-1) [note from Lisa: you may remember meeting another Beneventan fragment at the Lilly Library back in Indiana].

It was wonderful to have Lisa as a virtual guest at UCR; I wish she could stay longer— I look forward to our next actual visit, April 10 to April 12, 2014, at the annual meeting of the Medieval Academy of America at UCLA.

***********************************

Waving goodbye to Melissa, we’ll get back on the 10 and head eastward through the mountains and across the desert to Arizona. See you in Tempe!

* Important Geek Tip: Only “mundanes” or uncool outsiders to Science Fiction Fandom say ‘Sci Fi.’

All I found was fog and rain, but my visit to the Linda Lear Center for Special Collections and Archives was well worth the effort.

All I found was fog and rain, but my visit to the Linda Lear Center for Special Collections and Archives was well worth the effort.