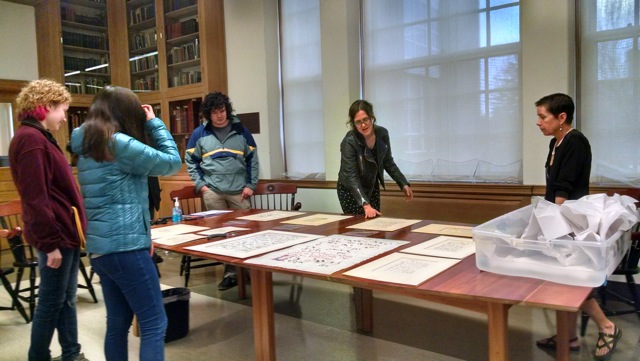

My last visit to the University of Wisconsin – Madison took place in 2014. At that time, I blogged about medieval material in two campus collections: Special Collections and the Chazen Museum of Art. It was a great pleasure to return to campus this weekend to deliver the keynote for the annual UW Graduate Association of Medieval Studies Colloquium, where I was treated to a dozen very impressive lectures by graduate students discussing their dissertation research. After lunch, I led a manuscript workshop before delivering my keynote at the end of day. The theme for the colloquium was “Blank Space,” loosely defined. For my keynote, I selected several UW early manuscripts to use as case studies in how medievalists – fragmentologists in particular – can fill the different varieties of blank space accrued by manuscripts as they journey through space and time: congenital, chronological, textual, codicological, and cultural. These methodologies are critical skillsets for medievalists.

A slightly-abbreviated version of my keynote follows. I am extremely grateful to GAMS President Helen Smith for inviting me to Madison, Research Services Librarian for Special Collections Carly Sentieri for sharing images and information, and to Maria Saffiotti Dale, Thomas Dale, Martin Foys, and all of the students and faculty who gave me such a warm welcome and shared their ongoing research.

Medieval manuscripts are much more than the texts they record and the illuminations they preserve. They are travelers through space and time, especially those that have made their way from medieval Europe, Africa, or Asia to 21st-century America. As they move through the centuries and across the miles, they collect information – signs of use, readership, and ownership – but they also accrue damage. That damage may lead to the loss of evidence along the way. Filling these blank spaces is reparative and, by extension, imperative.

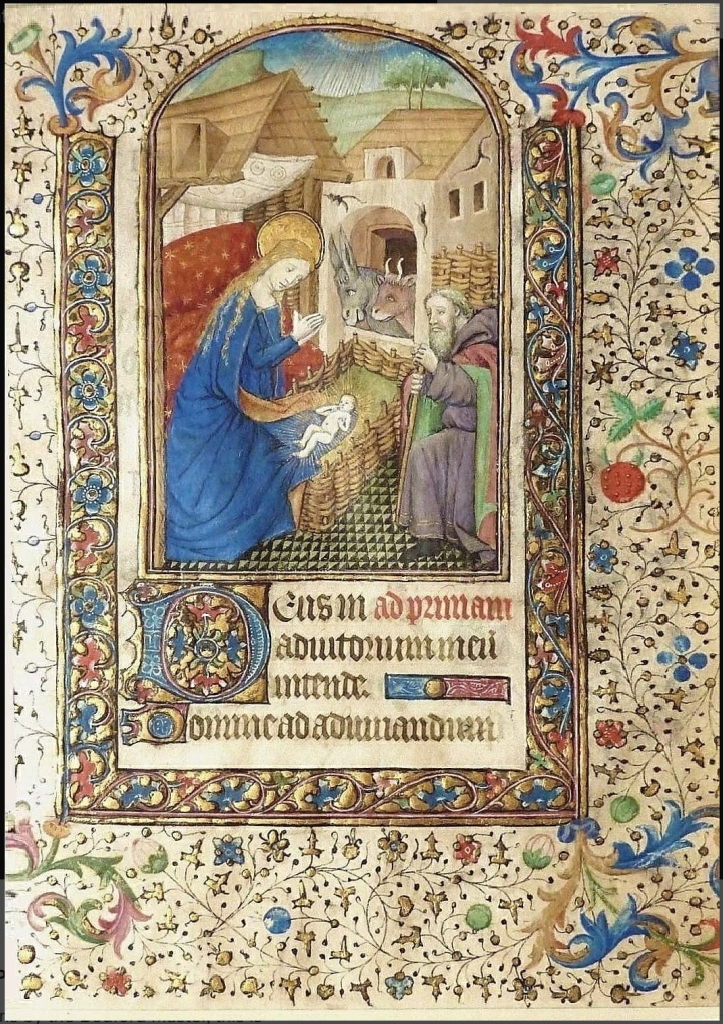

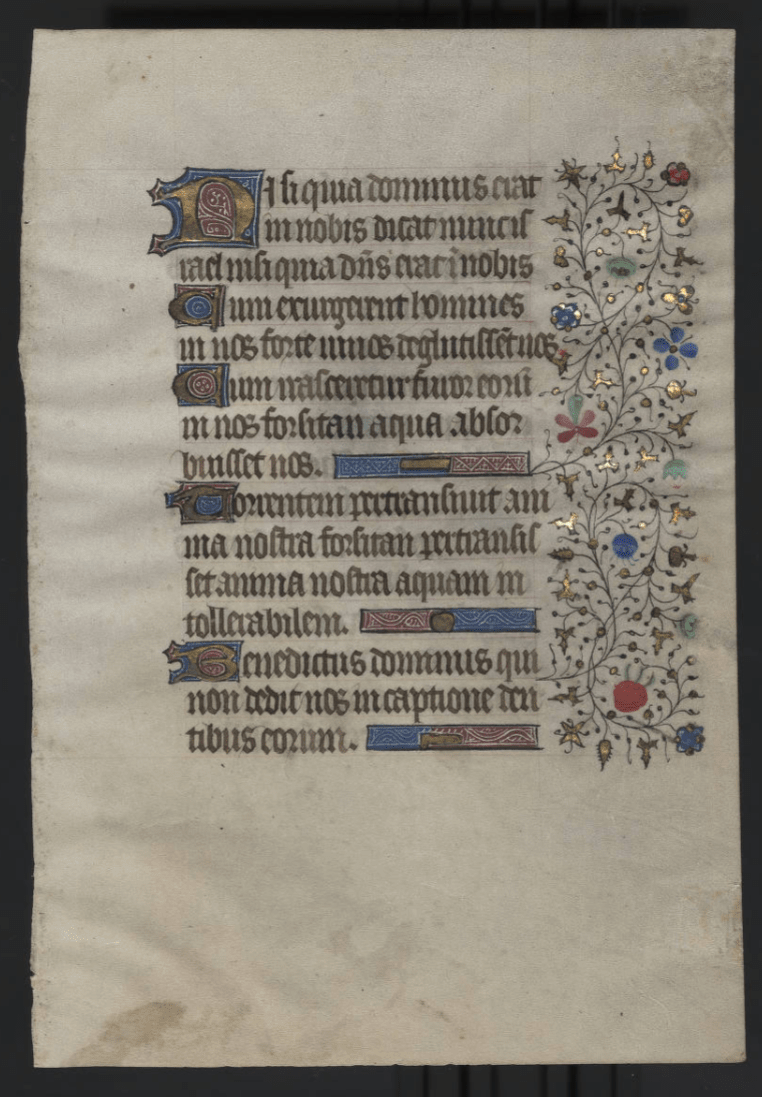

Our first case study is Special Collections Manuscript 161, a Book of Hours written in mid-15th-c. France. Unlike the damaged objects we’ll look at next, this manuscript was born with blank spaces, ten of them in fact. Only one miniature was filled in, the first in the Hours of the Virgin series, illustrating the Annunciation (left). By looking at the surrounding textual context, and knowing what we know about traditions of illustration in late medieval Books of Hours, we can fill these blanks and posit what should have been. The frame below, which opens the Hours of the Cross, should have held an illustration of the Crucifixion, for example.

These are physical, and congenital, blank spaces. But this manuscript also has a chronological lacuna. How can we fill in the blanks of its journey from 15th-century France to 21st-century Wisconsin? Let’s start with the evidence within the manuscript itself. The calendar includes a notice in red – indicating that it is particularly important – for the Feast of St. Lazarus on October 20, a date specifically celebrated in Autun in central France. In addition, two contemporary prayers at the front of the manuscript invoke St. Melanius (Bishop of nearby Troyes) and a very obscure virgin saint named Hoyldis, also venerated in the same region. That internal evidence places the manuscript’s origins in or near Autun. Moving forward in time, we find early inscriptions by members of the French Grailleult family at the back of the codex.

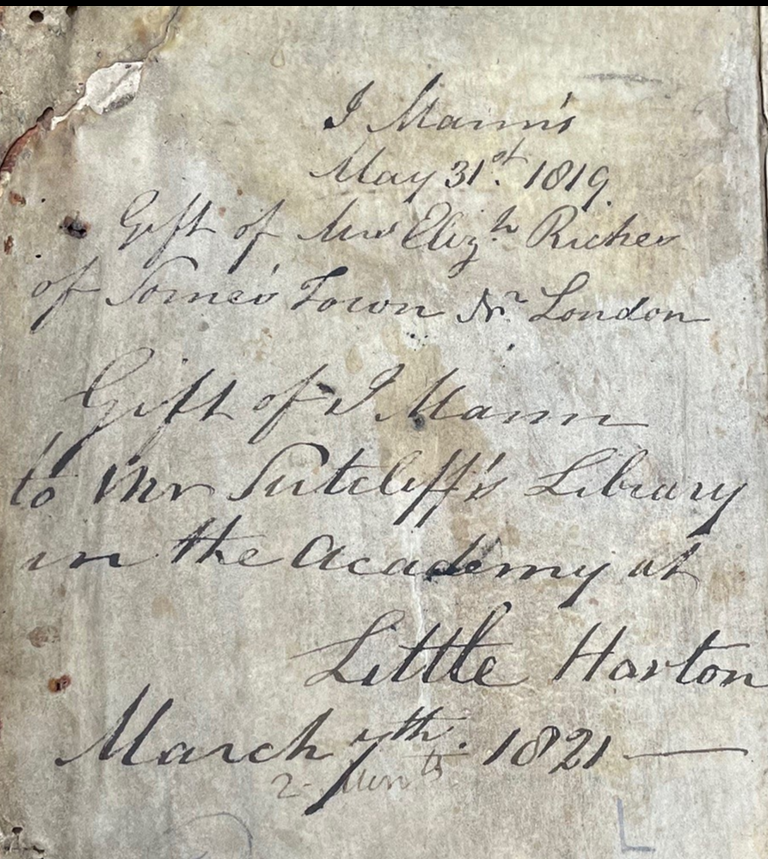

By the nineteenth century, the manuscript had crossed the Channel; inside the front cover (left) we are helpfully informed that the codex had been owned by one Elizabeth Riches of “Sorne’s Town near London” (likely today’s Shorne – identified by UW Professor Martin Foys, who knows a thing or two about the philology of English rural placenames). In 1819, Riches gave the manuscript to “J. Mann,” and Mann gave it in turn to “Mr. Sutcliff’s Library in the Academy at Little Horton” in 1821. A bit of internet research identifies Mr. Sutcliff as Baptist preacher John Sutcliff, whose library was donated to Horton Academy (now Rawdon College) when he died in 1814. At the Academy’s Jubilee in 1854, Mr. Sutcliff’s Library was described as “Consisting of nearly three thousand volumes, chiefly of the works of Continental, American, and our own [that is, Baptist] divines, embracing almost all subjects, it was peculiarly fitted for the Theological Institution. Many of the works are rare and difficult to procure.” Miss Riches’ donation would have been a welcome addition to this impressive collection.

That takes us up to 1821, which is as far as we can go given the evidence in the manuscript itself. We don’t know when, or under what circumstances, the manuscript was de-accessioned by the Academy library. But thanks to the extraordinary online resource the Schoenberg Database of Manuscripts, which I have mentioned in numerous posts, we can make our way from England to Wisconsin. If we search the Schoenberg Database for Books of Hours associated with Autun with 106 leaves (or 109, since some dealers count the added leaves at the end), we find multiple sales of this very manuscript, along with a lengthy trail of ownership. All of this information had been lost by the time the manuscript arrived in Madison. Thanks to the Schoenberg Database, we can fill in the chronological blanks and recover this manuscript’s history by tracking it through space and time

The manuscript was sold by Sotheby’s London five times: in 1911, 1937, 1943 (from the collection of Albert M. Patrick in Birmingham, UK), 1945, and 1981. In the 1911 Sotheby’s catalogue, the UW manuscript is clearly identifiable as lot 591: the dimensions, the number of lines, and the description of the number of blank frames all confirm the identification (with thanks to British scholar Laura Cleaver for the image). At that sale, the manuscript was sold to a London bookseller named Dobell for £7. Dobell offered it unsuccessfully for £12 in 1911, and, with more success, in 1912, which was when it was likely acquired by a British collector named William Moss of Sonning-on-Thames, a lovely country village not far from London (it’s where George and Amal Clooney live, so you know it’s fancy). Moss owned the manuscript until 1937, when (as Laura Cleaver informs me) his doctor advised him that he needed to go abroad for the good of his health and he sold most of his collection at Sotheby’s: the catalogue politely describes him as “changing his residence.” After sales in 1943 and 1945, Sotheby’s sold the manuscript for the last time in 1981, and San Francisco dealer Bernard Rosenthal sold it to the University of Wisconsin four years later.

This codex was born with blank space. By the time it reached Wisconsin, the provenance had been lost and the manuscript had acquired chronological lacunae that we can now fill, tracing its journey from Autun to Shorne to Little Horton to Sonning-on-Thames to Birmingham and, eventually, to Madison. But manuscripts may acquire other types of blank spaces as they move through space and time. It is the sad fate of uncounted manuscripts – tens of thousands, at least – that they have not survived the journey from there and then to here and now intact. Aside from the damage inflicted by fire, insects, water, and war, human hands have taken a toll as well, as manuscripts were taken apart by late-medieval binderies to use as binding scrap, or cropped by collectors, or dismembered by modern biblioclasts in the name of capitalism. That destruction leaves its own kind of blank space.

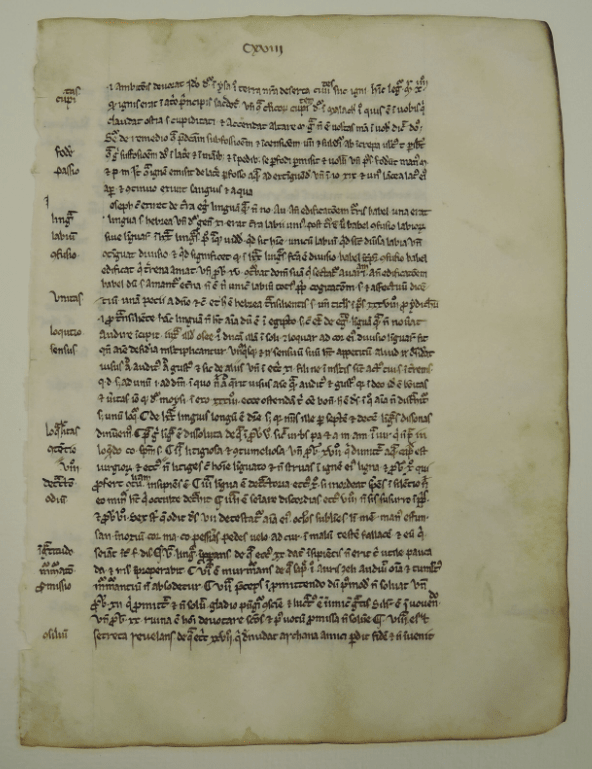

Let’s start with the two small fragments that together comprise UW MS 186 (below). The shape and staining on these two little bits identify them as having been used as structural components in an early-modern binding, and while a note in the folder says that they were removed from a 1546 edition of Paulo Giovio’s Elegies printed in Venice, I can confirm that they were NOT removed from UW’s copy of that book. They must have been removed from a different copy before UW acquired them. The script looks 13th-century Italian to me, so it makes sense that it would have made its way into the binding of a book printed in Italy.

But what was it before it was a pastedown inside of a sixteenth-century Venetian printed book? A Google search identifies the text as “De conflictu vitiorum et virtutum,” a very popular work on Virtues and Vices attributed to the 8th-century Abbot Ambrosius Autpertus, of the Beneventan house of San Vincenzo al Volturno. The text is edited in the Patrologia Latina, so it’s not difficult to identify the specific portion preserved on these fragments. The format of the fragments – tall and narrow – suggests that the original leaves had two columns. In a two-column manuscript, the recto and verso of the innermost column, at the gutter edge, are not consecutive with one another, while the recto and verso of the outer column are. We have both situations here. The recto and verso of the first fragment are consecutive, identifying this as the outer column of its original leaf. By comparing the layout of the fragment with the text of the edition, we can figure out approximately how much text is missing, filling in the blank space of the missing inner column on both recto and verso. Was the other fragment part of that same leaf? Unfortunately not. The second fragment was cut from a different leaf, as the text is not consecutive with the first fragment. And because the recto and verso of the second fragment are not consecutive with each other, we can identify this as the inner column of its leaf.

The next question is: how much is missing between the verso of the first fragment and the recto of the second? Exactly one column! This means that the second fragment immediately follows the missing column on f. 1v. These fragments were originally part of two consecutive leaves (below).

The outer (missing) column of the second fragment would have preserved the last few lines of the Virtues and Vices homily; the text on the verso remains unidentified but was likely a lapidary of some kind, a text describing the properties of gemstones.

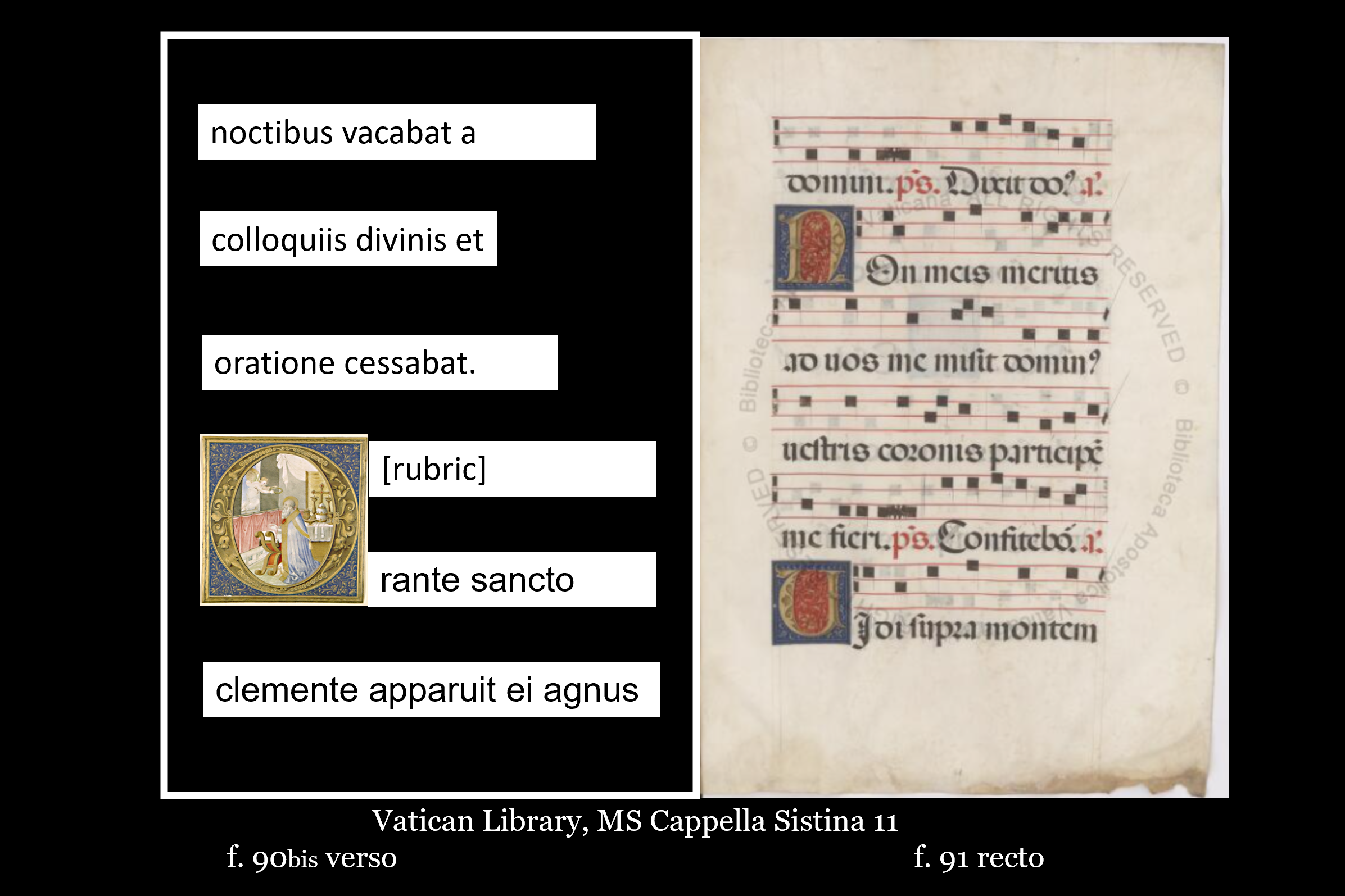

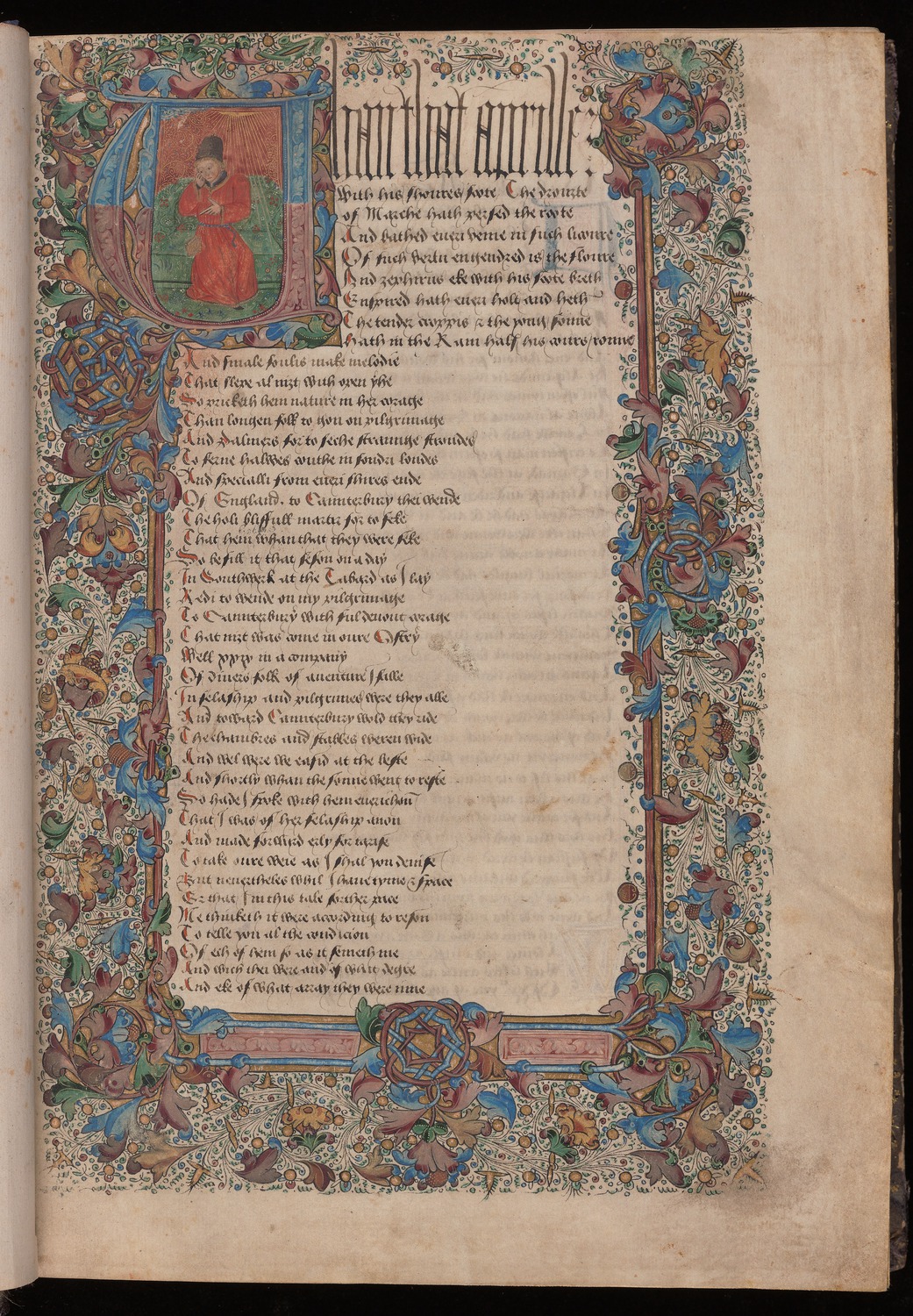

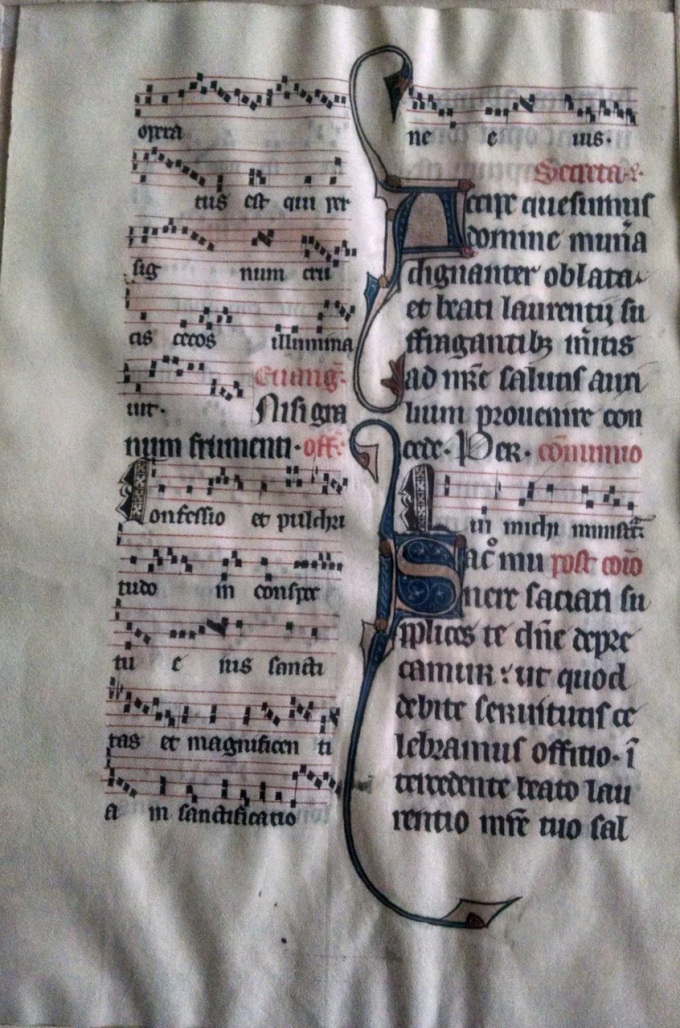

We can use a similar methodology to investigate the blank space surrounding this gorgeous historiated initial, Chazen Museum 2001.30, which I mentioned in the 2014 blogpost. The initial has been attributed to Vincent Raymond de Lodève, a French artist active in Italy in the middle of the sixteenth century. And thanks to a brilliant piece of art historical and codicological research by Maria Saffiotti Dale, formerly the Chazen Museum Curator of Paintings, Sculpture, and Decorative Arts, we now know that this initial was once part of an antiphonary made for use in the Sistine Chapel itself, a Vatican Library manuscript known as Cappella Sistina 11. Maria’s 1998 article demonstrated that the manuscript’s five missing leaves had initials on them, initials that were later cropped out and that she was able to identify (she later convinced the powers-that-be at the Museum to acquire the cutting for the Chazen collection). It’s not entirely clear when the damage occurred, although it’s certainly possible – likely even – that the leaves were removed during the famed looting of the Sistine Chapel by Napoleonic forces in the late 18th century. We also know from archival records that Vincent Raymond painted these initials in 1539. It was Maria who identified the source manuscript and determined the location of the missing initials in the original codex.

The Chazen initial was cut from a missing leaf originally found between folios 90v and 91r (above). You can easily tell that something has gone wrong in this opening because the page on the left is the dark (hair) side of the parchment, while the facing page is the creamier (flesh) side; elsewhere in the manuscript we find, as expected, flesh side facing flesh side, and hair side facing hair side. Maria determined that the kneeling Pope represents not just any old generic Pope but Clement I himself, whose feastday is November 23. When such initials are cut from their parent manuscript – a not uncommon practice – the miniatures present themselves by default as self-sufficient works of art, especially when framed and mounted (I’ve written about the semiotic implications of this practice here). But such miniatures are decontextualized. Without Maria’s work, we would not be able to identify this rather generic kneeling Pope as Clement I or be able to restore the initial to its rightful place, not only within the manuscript but on its original leaf. This process is facilitated by the survival and accessibility of the fragmentary text on the other side.

Often, such miniatures are adhered to a backing that obscures any textual evidence, a backing that might not be able to be removed without damaging the cutting. Not all Curators are as steeped in the work of identifying cuttings as is Maria Saffiotti Dale, and knowing how important the hidden evidence can be, she requested that the dealer from whom the Chazen acquired the cutting engage a parchment conservator to 1) determine if the backing could be safely removed, and 2) after making that determination, actually remove the backing, so that she could study the textual evidence.

The removal of the miniature left a lacuna in the leaf, and the missing leaf is itself a lacuna that surrounds the miniature. Can we re-contextualize the miniature by filling that blank space?

Because the leaves were foliated after the leaf with the miniature was removed, the missing leaf has no folio number. We’ll call it “90bis”, which means the second folio 90. We can’t tell from looking at the cutting whether it was taken from the front (recto) or back (verso) of the leaf, but we can figure it out. Here’s how: by searching the CANTUS database for a chant for Lauds of St. Clement that starts with [O] and ends with the word [domini] (on folio 91r), we find the Lauds antiphon “Orante sancto Clemente apparuit ei agnus domini,” an identification made by Maria several years ago. If the initial is placed near the bottom of the verso, the chant is a perfect fit:

If we turn back to the other side, we find the fragmentary text “evangelium…at in pectore,” and, knowing where the initial fits on the page, we also know where this fragmentary text fits on the recto. If we search CANTUS for the phrase “in pectore,” we find exactly what we’re looking for: “Virgo gloriosa semper evangelium Christi gerebat in pectore suo non diebus neque noctibus vacabat a colloquiis divinis et oratione cessebat,” a Vespers antiphon for St. Cecelia, whose feastday just happens to be on Nov. 22, the day before Clement! What about the rest of the missing text? We can use CANTUS to complete the chant that begins at the bottom of f. 90v, which also fits perfectly on f. 90bis recto. We’ve now reconstructed both sides of the original leaf and can digitally restore it to the codex.

These case studies demonstrated how we can fill in the blanks left when a leaf is damaged. The next case study will fill a codicological blank space.

This UW Special Collections bifolium (no shelfmark yet, as it was acquired recently) was removed from its quire early on, after which it was trimmed and folded to create a bookcover. The text can be easily identified as Cicero’s De officiis. The style of script places it in Italy in the 15th century, right in the middle of the humanistic revival of classical learning. It’s a very well-known work, so it was simple to find an edition online and identify the text preserved on each of these two conjoint leaves. On the left, chapters 47-52, and on the right, chapters 64-69. That’s a pretty big lacuna to fill, from chapters 53 to 63. But with an edition at hand, we can figure out not only how much text is missing but also calculate the number of intervening leaves and, by extension, bifolia. So this is not only a textual blank space but a codicological one as well.

Each leaf of the fragment, recto plus verso, is approximately 3,700 characters, including spaces. The number of characters between the end of the verso and the start of the conjoint recto is 7,883, including spaces. That is almost exactly two leaves. And when you have a conjoint bifolium with two leaves separating them? Those two leaves must be an intervening bifolium. And not only a bifolium, but the central bifolium of the quire, regardless of how many bifolia there were originally, because the leaves of that missing bifolium would have been both consecutive and conjoint. So now we know that the Wisconsin fragment was originally the second bifolium from the center of its quire.

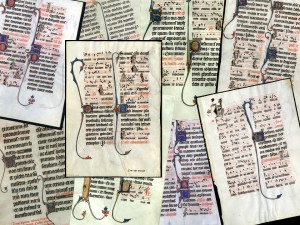

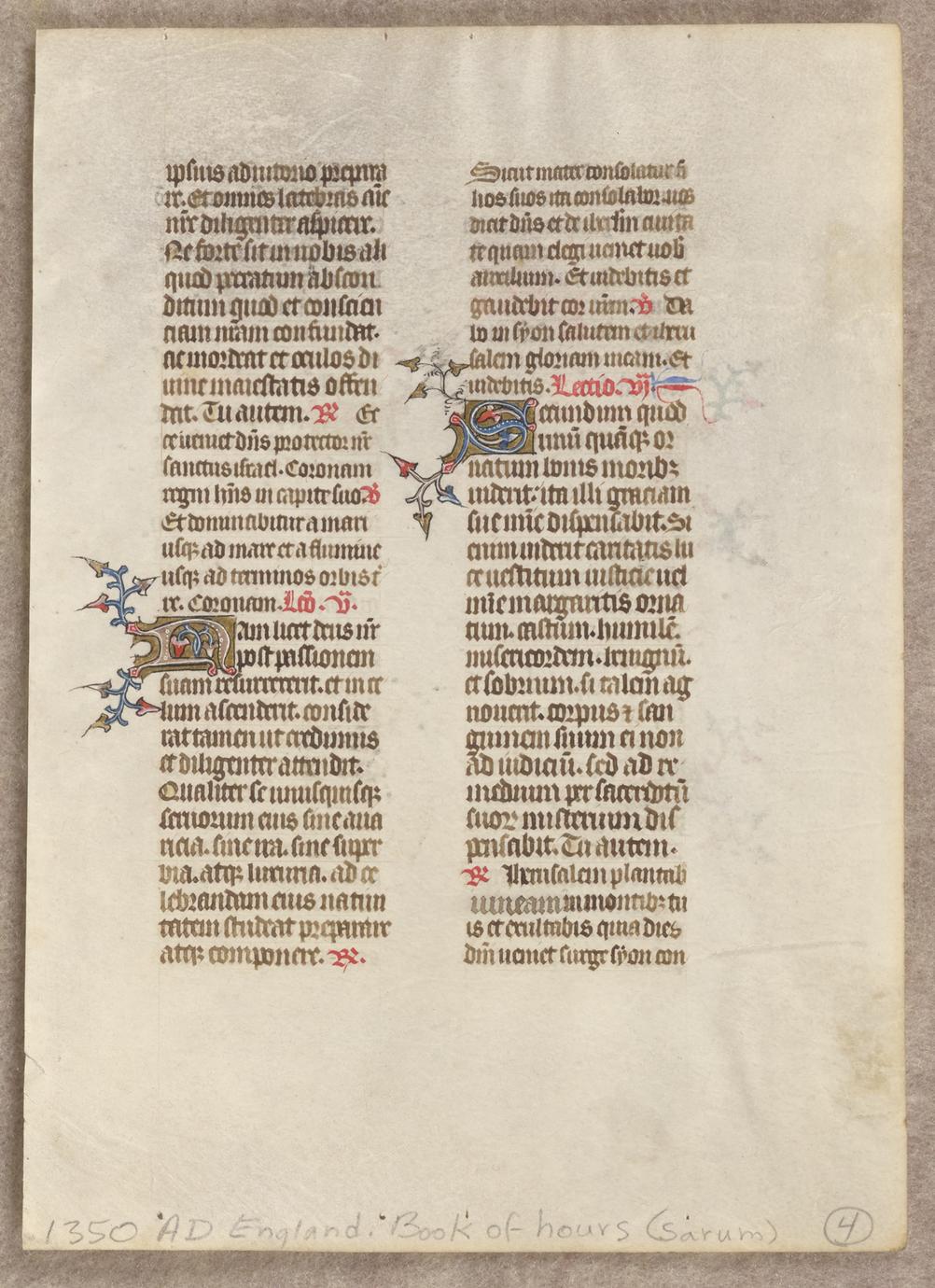

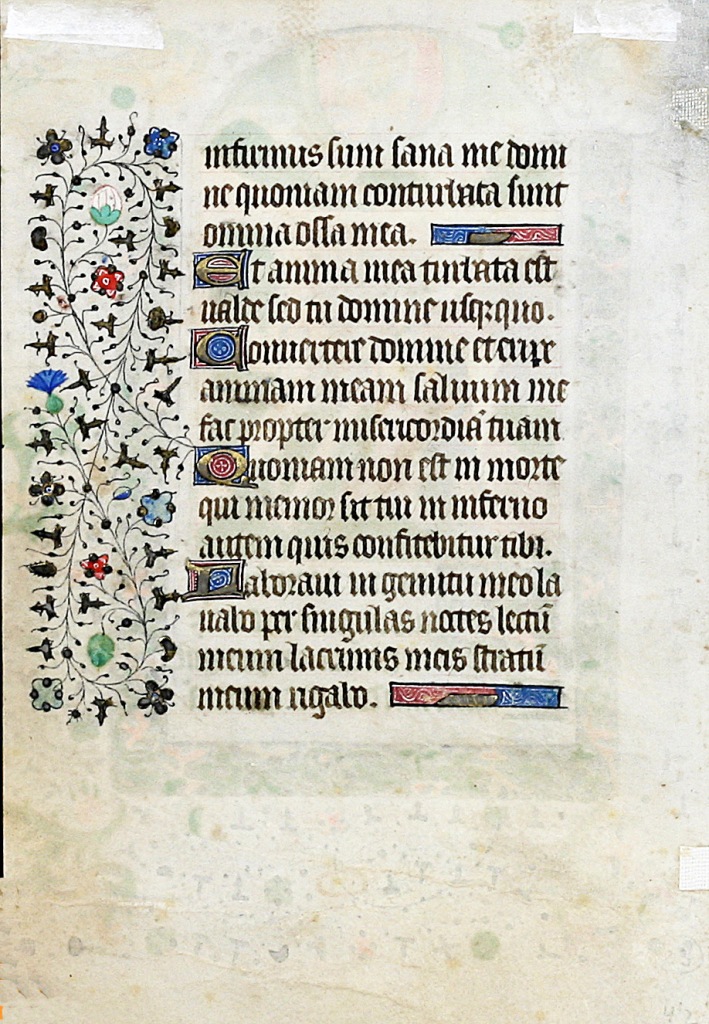

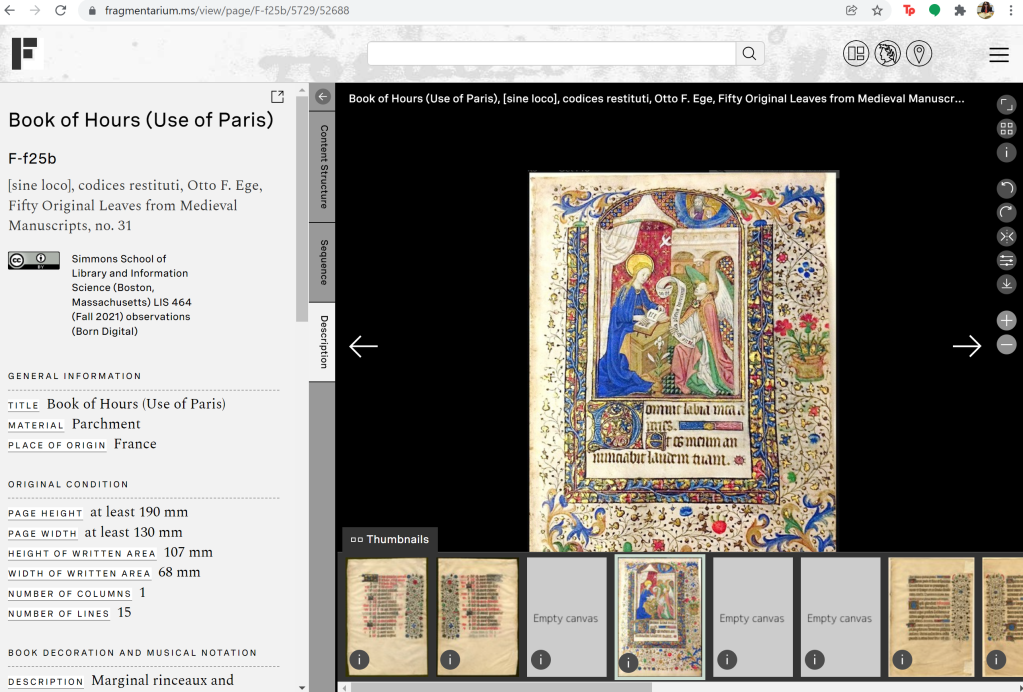

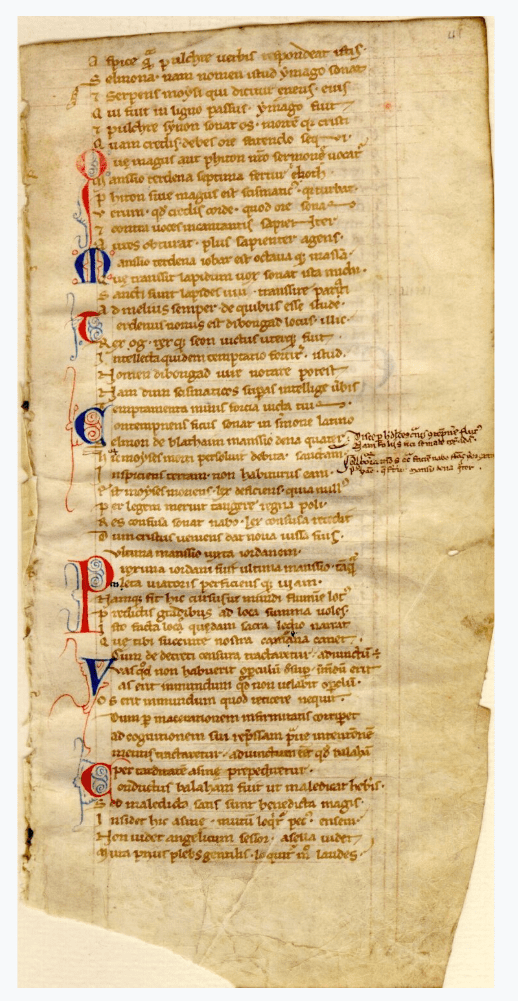

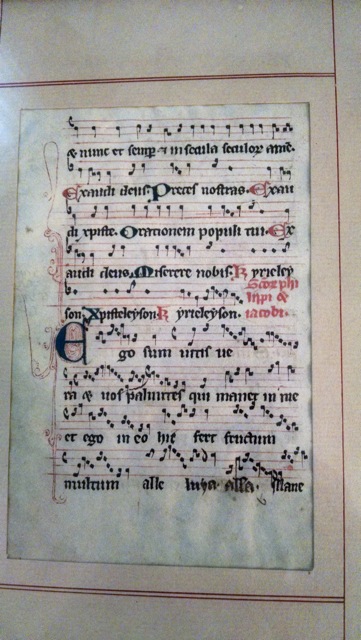

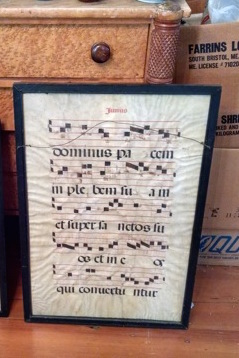

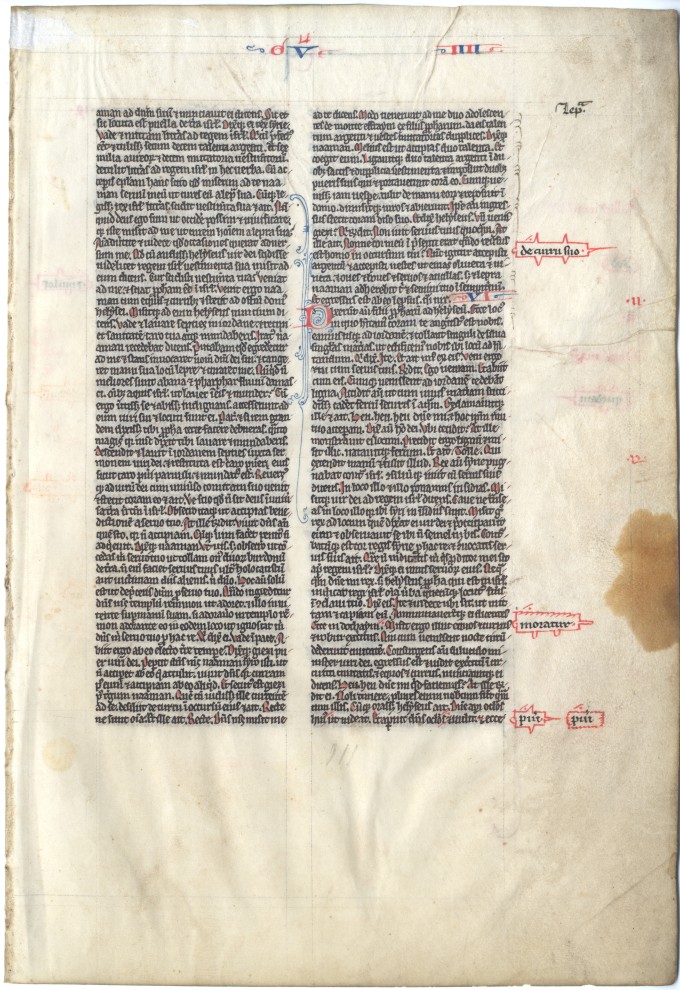

For our final case studies, we’ll be looking at the space surrounding whole single leaves like MS 170a, no. 4. As my readers will know, in the first decades of the twentieth century, it became common for bookdealers to dismember manuscripts and distribute leaves one by one. They knew they would make more money this way than by selling one leaf to one buyer. Each of these leaves presents itself as a distinct object, whole in and of itself, but in truth a leaf like this one is surrounded on all sides by lacunae, and the sum of these lacunae is the ghost of the lost book. The more leaves we can find, the more we can manifest the lost codex.

This lovely fourteenth-century fragment from France originally belonged to a Breviary. The leaf preserves Office liturgy for the second Sunday in Advent; we know this because the responsories can be identified in the CANTUS database. But guess what? There’s ANOTHER leaf of this manuscript on campus, at the Chazen Museum (accession no. 2013.37.61). This leaf, by a very nice co-incidence, preserves liturgy for the THIRD Sunday in Advent. These leaves were near one another in the original manuscript but came to Madison decades apart and by completely different routes, so it’s satisfying to be able to reunite them. By putting them side-by-side, we’ve already begun to fill the blank space left when the codex was dismembered.

The Chazen leaf was given to the Museum in 2013 by Barbara Mackey Kaerwer, who purchased it in 1954 from New York dealer Hans P. Kraus. The Special Collections Library, on the other hand, doesn’t have any information about exactly when or how their leaf was acquired – this is quite common with single leaves, which do tend to slip through the cracks. But I’ve figured out exactly how it got there.

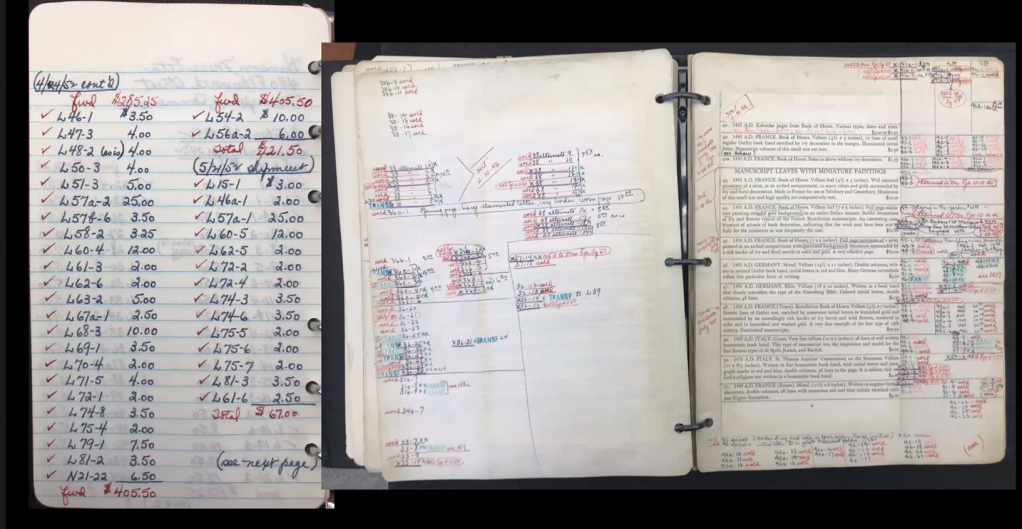

According to my research on New York dealer Philip Duschnes and his sales of manuscript leaves, Duschnes was selling leaves of this manuscript from 1939 through 1948, although I have not yet been able to identify when or under what circumstances the codex was dismembered. But Duschnes wasn’t the only one selling leaves of this manuscript. You will likely not be surprised at this point to learn that leaves from this breviary were also sold by our old friend Otto F. Ege, as I discussed in my Purdue blogpost from a few weeks ago. According to the Lima Public Library sales ledgers, the Library sold 133 leaves from this manuscript between 1935 and 1941, making this one of Ege’s most popular manuscripts. The buyers were scattered across the country from Los Angeles to Nova Scotia and from Oregon to South Carolina.

From Lima, the leaves were sold to buyers in 51 cities across 24 states, including three in Wisconsin: Margaret Kaestner of Fond du Lac bought one in 1940 for $3; Mrs. Leslie Rowley of Madison spent $6.50 for hers in 1946, and, in 1944, the third was purchased for $6.50 by a Madison gentleman named George C. Allez. Allez was the Director of the University of Wisconsin Library School from 1941-1950. According to the Lima ledgers, he purchased six different leaves in 1944: Gwara Handlist numbers 5, 18, 24, 122, 123, and 244. These are the exact same handlist numbers which can be found today in the Special Collections MS 170a box! That can’t be co-incidence…these must be the very leaves that Allez bought in 1944.

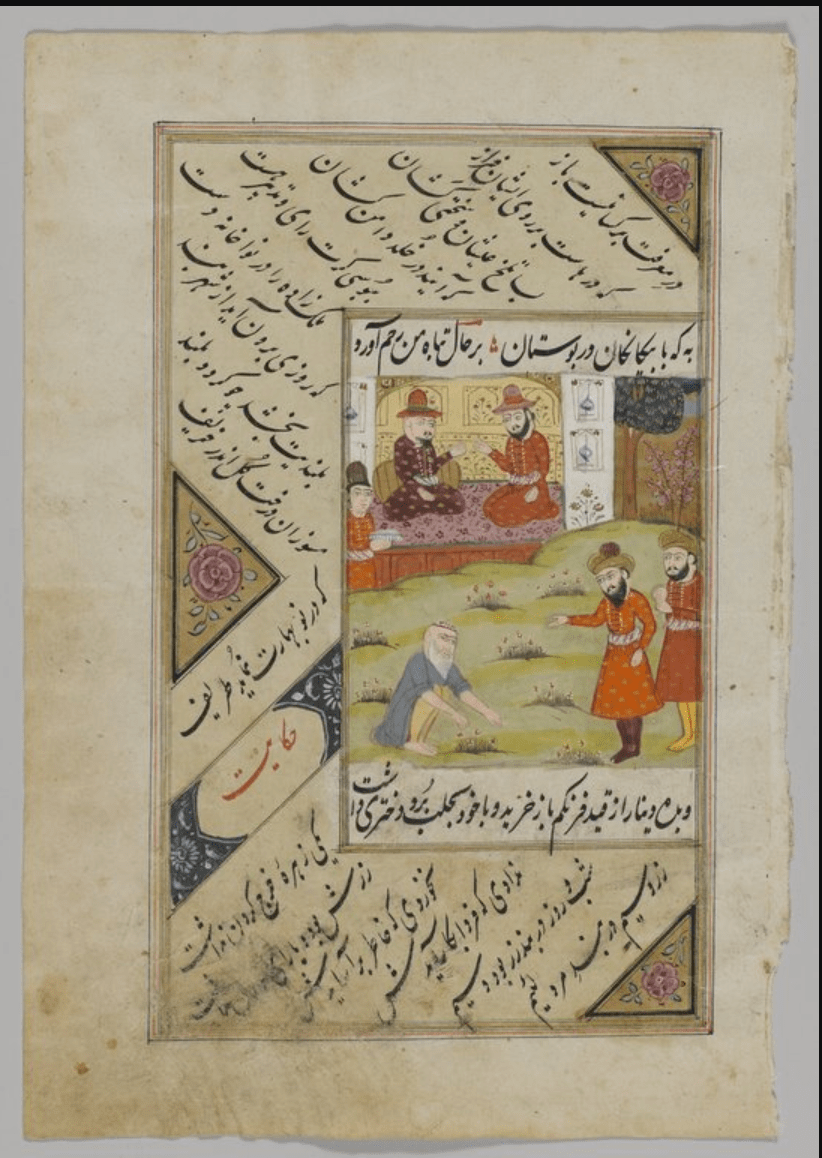

There’s one more type of blank space that fragments leave behind: a cultural lacuna. Dealers in the 20th century weren’t just dismembering Latinate manuscripts. Even more enticing to American buyers were the “exotic” manuscripts in non-Latinate alphabets such as Ethiopic, Syriac, Tibetan, Arabic, Greek, Hebrew, and Persian, to name just a few. Such manuscripts suffered a traumatic double-decontextualization that stems from colonialist praxis: the removal of a codex from its community of origin – a community to whom it may have been sacred – followed by its dismemberment and the loss of any evidence or knowledge about its point of origin or history, the acquisition of leaves by collectors who were exoticizing these “others,” and the deposit of these leaves in collections that through no fault of their own may not have staff with linguistic or content expertise to provide them with appropriate metadata to facilitate discoverability.

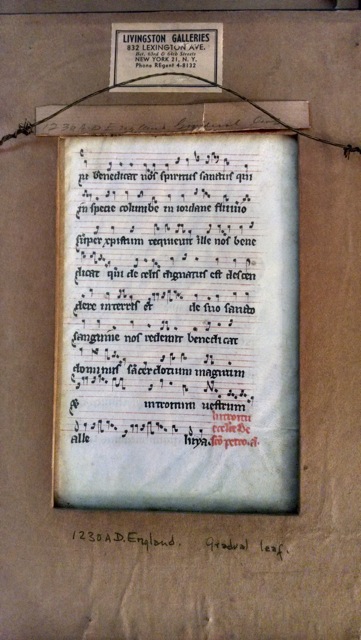

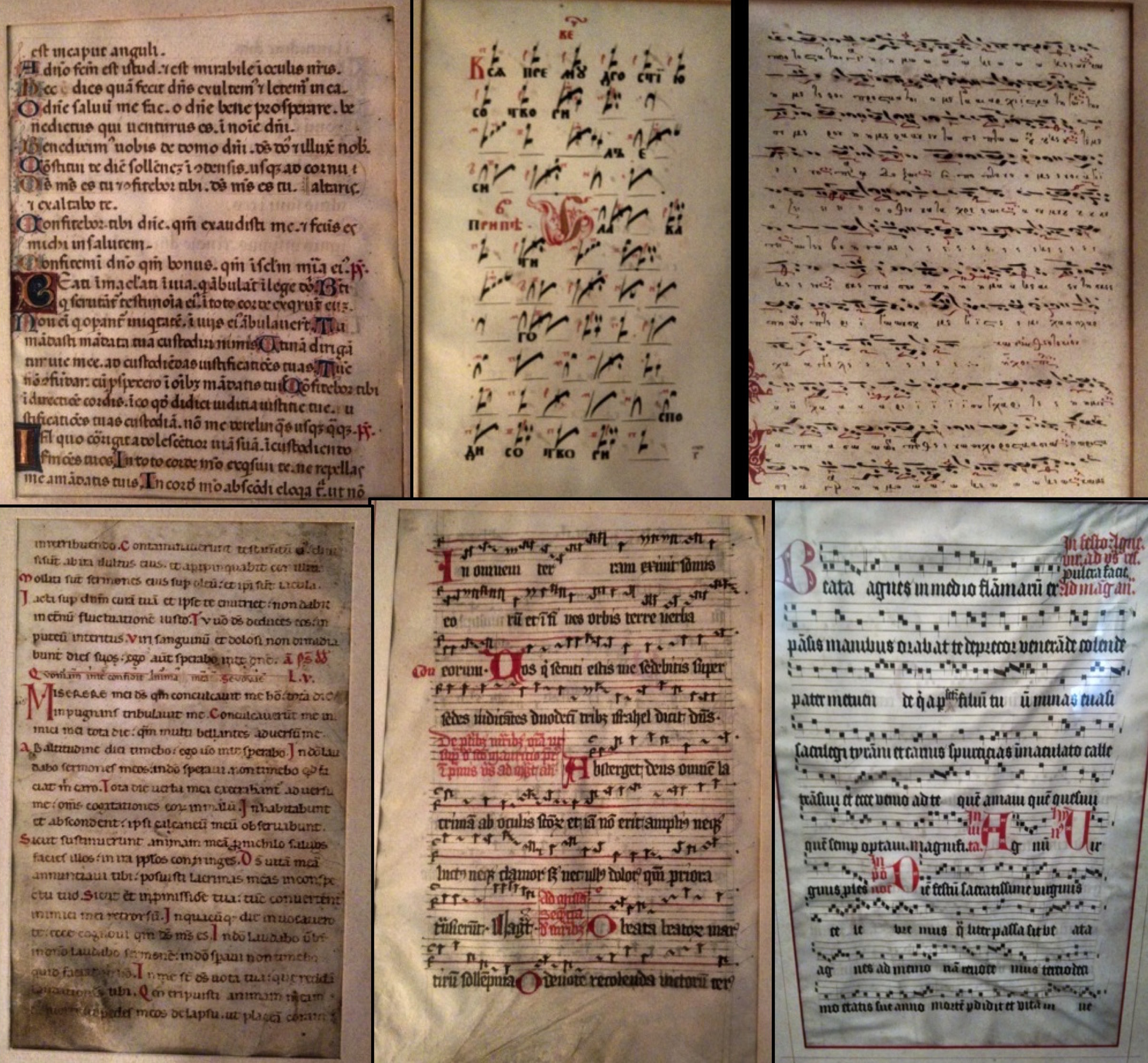

A prime example of this phenomenon is the Ege portfolio rather unfortunately titled “Fifteen Original Oriental Manuscript Leaves.” Ege created dozens of copies of this portfolio by dismembering fifteen manuscripts of non-European origin, seeing these as interesting examples of different writing systems. One of these portfolios belongs to the University of Wisconsin, donated to the University in 1986 by Ege’s daughter Elizabeth Freudenheim in honor of her own daughter Jo Louise earning a UW PhD in Nutritional Sciences. The set (shelfmark MS 195) includes leaves from several Arabic Korans, a Syriac prayerbook, an Armenian lectionary, an Ethiopic hymnal, a collection of Persian poetry, a Cyrillic hymnal, and part of a Tibetan prayer scroll, among others (below, l-r t-b).

Libraries often miscatalogue these leaves, because Ege’s descriptions are all that cataloguers have access to, especially in a Library where there may not be someone on staff, or even on campus, who can read Tibetan, or Syriac, or Ethiopic. For example, the Armenian lectionary (above, top row, third from the left) is generally said to have been written in the fifteenth century, although Ege skeptically also cites a now-missing colophon dating the manuscript to “1121 A.D.”

What Ege didn’t realize is that the Armenian calendar is quite different from the Gregorian. Something dated 1121 in Armenian was in fact written in Anno Domini 1671…you have to add 550 to convert the date. So the manuscript was actually written in the 17th century. There’s no reason a cataloguer would be expected to know that the colophon’s date was according to the Armenian calendar, because that information has been lost. The Armenian leaf is an important example of how critical it is to consider and respect the cultural context in which a leaf was written and to acknowledge the damage inflicted on a manuscript when it is removed from its community of origin, dismembered, and decontextualized. That’s a blank space we should all try to fill.

The conceptual framework underlying a MARC record is replication. If you’ve just purchased a paperback copy of the third edition of the

The conceptual framework underlying a MARC record is replication. If you’ve just purchased a paperback copy of the third edition of the

The

The

The Beauvais Missal

The Beauvais Missal

The final leaf (shown to the right), from a large choirbook, cannot be positively identified in Gwara’s handlist, but it may be lurking in there somewhere.

The final leaf (shown to the right), from a large choirbook, cannot be positively identified in Gwara’s handlist, but it may be lurking in there somewhere.

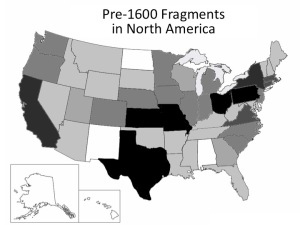

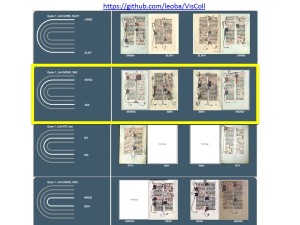

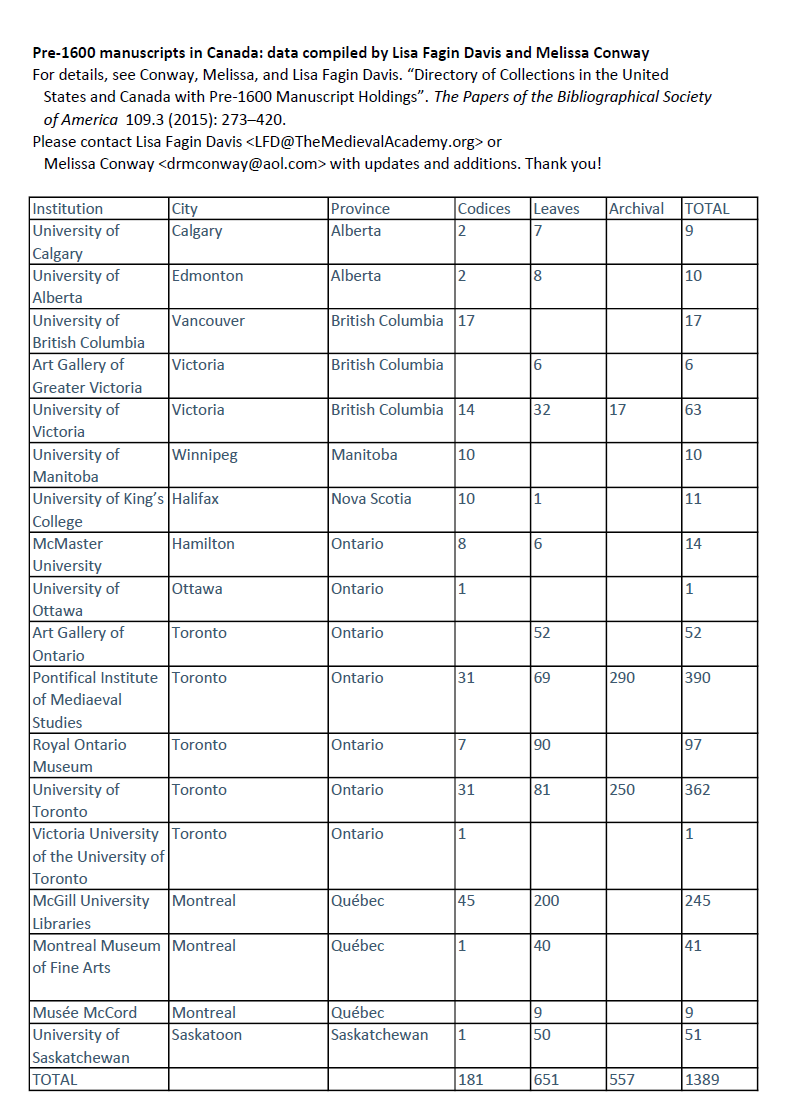

In our road trip around the U.S., we’ve encountered pre-modern European manuscripts in 47 of the lower 48 states, plus Hawaii and Puerto Rico. There are some nice visualizations of the data compiled by myself and Melissa Conway

In our road trip around the U.S., we’ve encountered pre-modern European manuscripts in 47 of the lower 48 states, plus Hawaii and Puerto Rico. There are some nice visualizations of the data compiled by myself and Melissa Conway

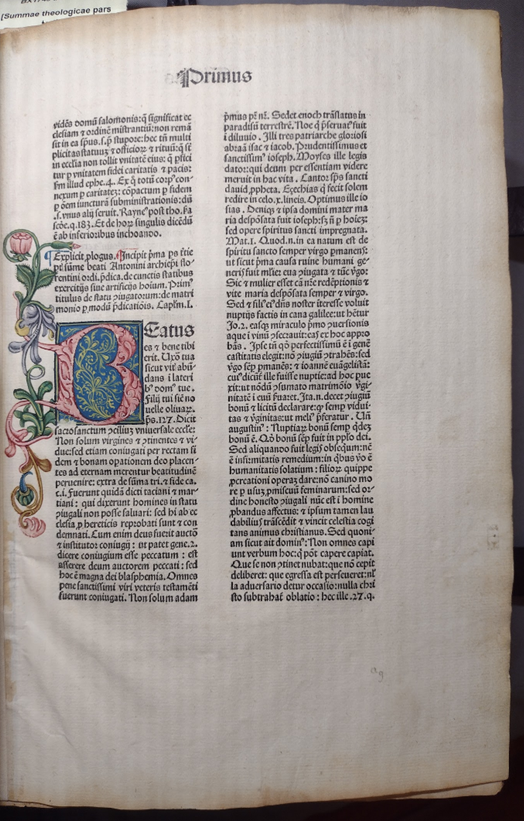

Missals and MSS Prior to the Invention of Printing.

Missals and MSS Prior to the Invention of Printing.

Next time, we’ll catch a ferry to Nova Scotia to start our tour.

Next time, we’ll catch a ferry to Nova Scotia to start our tour.