Last week, I traveled to the University of Leeds with 2,000 other medievalists from around the world to participate in the International Medieval Congress. This post is a somewhat-abbreviated version of the paper I gave on the last day of the Congress, titled “Fragments and Fragmentology in North America.”

The corpus of manuscript leaves in North America presents problems and opportunities distinct from those facing and offered to other national collections, due to both the content of the corpus and the historical circumstances of its development. And I’m primarily going to be referring to whole, single leaves; cuttings and binding fragments such as those at right tell a very different story than the one you are about to hear.  Binding fragments result from medieval and early modern recycling of worn or outdated manuscripts, not from a collector’s destructive whim. Manuscripts were being cut up “for pleasure and profit” (in the words of Christopher de Hamel) as early as the eighteenth century. Throughout the nineteenth century, collectible illuminated initials and miniatures were cut out close to the borders, the remnant text thrown out. This practice resulted in sales and collections of free-standing tightly-cropped initials, arranged cuttings adhered to highly-acidic paper, and elaborate collages such as the one shown at the left.

Binding fragments result from medieval and early modern recycling of worn or outdated manuscripts, not from a collector’s destructive whim. Manuscripts were being cut up “for pleasure and profit” (in the words of Christopher de Hamel) as early as the eighteenth century. Throughout the nineteenth century, collectible illuminated initials and miniatures were cut out close to the borders, the remnant text thrown out. This practice resulted in sales and collections of free-standing tightly-cropped initials, arranged cuttings adhered to highly-acidic paper, and elaborate collages such as the one shown at the left.  Most collectors on both sides of the Atlantic were not particularly interested in text or context, only in the pictures.

Most collectors on both sides of the Atlantic were not particularly interested in text or context, only in the pictures.

Beginning in the early twentieth century, dealers began breaking books and selling them off page by page. Was this in response to demand from collectors or was it a profit-driven impulse? It’s unclear. What is clear is that during this period, dealers began to sell, and collectors began to buy, entire pages. The United States, with its new industry-fueled wealth, was a primary beneficiary of this flooded market. From Masters of Industry to small-town collectors, major museums to small colleges, bibliophiles in the United States were clamoring for matted and framed leaves, in particular leaves from Gothic Books of Hours and Italian choirbooks. Dealers saw no harm in destroying these manuscripts. It was an example of a market economy on one side, as demand drove prices up, and economies of scale on the other. Dealers knew they would make more money selling 250 leaves to 250 buyers than if they offered a whole codex to one buyer. As a result, today there are tens of thousands of single leaves in several hundred U.S. collections.

The publication of Seymour de Ricci’s 1935 Census of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts in the United States and Canada, its 1962 Supplement, and the Directory of Institutions in the United States and Canada with Pre-1600 Manuscript Holdings (co-authored by Melissa Conway and myself) give us three data points with which to analyze the development of the corpus of single leaves in the United States. For additional information about the Directory, see Melissa Conway and Lisa Fagin Davis, “The Directory of Institutions in the United States and Canada with Pre-1600 Manuscript Holdings: From its Origins to the Present, and its Role in Tracking the Migration of Manuscripts in North American Repositories,” Manuscripta 2013, Vol. 57, No. 2, pp. 165-181. The statistics and figures in the next few paragraphs are taken from that article.

In compiling our Directory, Melissa and I did not set out to produce a union catalogue of manuscripts, but rather a true census, a counting, with the goal of answering a question that many scholars have asked but no one had previously been able to answer, that is, just how many pre-1600 manuscripts ARE there in North America? And how has the landscape of medieval and Renaissance manuscripts in North America changed since the publication of the Census and the Supplement?

While a detailed history of the migration of early manuscripts to North America over the past two centuries has yet to be written, it is certain that by 1935, after the publication of the de Ricci Census, about 7,900 codices and 5,000 individual manuscript leaves had made their way to the North American continent. In order to formulate a meaningful comparison with today’s holdings, however, it is necessary to remove from this total the number of manuscripts in private collections, because contemporary collectors are more hesitant than were collectors in the 1930s to publicize their collections. The number of manuscripts in public collections in 1935, then, was around 6,000 codices and 2,500 leaves. By 1962, the number of manuscripts in public collections totaled 8,000 codices and 3,000 leaves.

As for today’s holdings, the current count is approximately 20,000 codices and 25,000 individual leaves—a total increase of 400% in fifty years. The total number of codices in public collections has gone up two and a half times; by contrast, the number of leaves has mushroomed nearly nine times. In addition, the number of public collections has grown from 195 to 207 to 499. Medieval and Renaissance manuscripts can now be found in every state in the Union except for Alaska and North Dakota. The collections holding manuscripts today that were not included in either the Census or the Supplement represent 60% of the total, 300 out of 499. Between them, these “new” collections hold about 1,800 codices and 9,000 leaves, a lopsided statistic when compared to the rest of the collections that demonstrates the dependence of “new” collections on the cheaper, more plentiful market in single leaves. These mostly small institutions with small acquisitions budgets were able to take advantage of the burgeoning market in single leaves to grow their teaching collections.

As for today’s holdings, the current count is approximately 20,000 codices and 25,000 individual leaves—a total increase of 400% in fifty years. The total number of codices in public collections has gone up two and a half times; by contrast, the number of leaves has mushroomed nearly nine times. In addition, the number of public collections has grown from 195 to 207 to 499. Medieval and Renaissance manuscripts can now be found in every state in the Union except for Alaska and North Dakota. The collections holding manuscripts today that were not included in either the Census or the Supplement represent 60% of the total, 300 out of 499. Between them, these “new” collections hold about 1,800 codices and 9,000 leaves, a lopsided statistic when compared to the rest of the collections that demonstrates the dependence of “new” collections on the cheaper, more plentiful market in single leaves. These mostly small institutions with small acquisitions budgets were able to take advantage of the burgeoning market in single leaves to grow their teaching collections.

This map above shows the relative number of manuscripts in 2015 – that is, codices and leaves – in each state. Not surprisingly, the greatest holdings (the darkest shading) correspond with well-known repositories and academic institutions in the Northeast, the Great Lakes region, and California. The picture changes a bit when we look just at singles leaves (below). Here we find in addition to the usual suspects leaf collections of distinction in the Midwestern states of Kansas, Missouri, and Texas, but especially Ohio, and if you go back and read this blogpost, you’ll understand why.

No story of manuscript leaves in the United States would be complete without a discussion of Otto Frederick Ege, bibliophile and self-proclaimed biblioclast. Ege spent most of his career as a professor of art history at the Cleveland Museum of Art in Ohio. He was a collector of manuscripts, recorded in the Census, but he was also a bookdealer. He is best known for breaking apart manuscripts and early printed books in the 1930s and 1940s, selling them leaf by leaf at a massive profit. He wasn’t the first to do this of course; other dealers had figured out that economies of scale worked in their favor if they sold 250 leaves to 250 buyers instead of one manuscript to one buyer. Ege defended his “biblioclasm” with what he considered the noble goal of putting a little bit of the Middle Ages within the economic grasp of even the humblest collector or smallest institution.

In a 1938 article in a “hobbyist” journal called Avocations, Ege explained:

“Book-tearers have been cursed and condemned, but have they ever been praised or justified?…Surely to allow a thousand people ‘to have and to hold’ an original manuscript leaf, and to get the thrill and understanding that comes only from actual and frequent contact with these art heritages, is justification enough for the scattering of fragments. Few, indeed, can hope to own a complete manuscript book; hundreds, however, may own a leaf.” His actions may have been misguided, but he was correct in one important respect; small collections throughout the United States that could never have purchased entire codices are the proud possessors of significant teaching collections of medieval manuscript leaves.

Thanks to the work of scholars such as A. S. G. Edwards, Barbara Shailor, Virginia Brown, Peter Kidd, William Stoneman and others, as well as a recent monograph by Scott Gwara, several thousand leaves from several hundred manuscripts that passed through Ege’s hands can now be identified in at least 115 North American collections in 25 states. In other words, more than 10% of the entire corpus of single leaves in the United States can be traced back to Otto Ege.

Ege leaf in its distinctive matte (from the collection at Rutgers University; the leaf has since been removed from the matte)

Ege used the leaves of several dozen manuscripts to create thematic “portfolios,” for sale. In other words, he would take one leaf of this manuscript, one leaf of that one, one leaf from a third, and so on, and pile them up into a deck of manuscript leaves, each of which was from a different codex. The leaves in these portfolios are always sequenced the same way. Number 5 in one portfolio comes from the same manuscript as Number 5 in every other portfolio of the same name. The most common of these portfolios are titled Fifty Original Leaves from Medieval Manuscripts; Original Leaves from Famous Bibles; and Original Leaves from Famous Books. The leaves were taped into custom mattes with a distinctive red-fillet border and Ege’s handwritten notes across the bottom, identified with Ege’s letterpress label, and stored in custom buckram boxes.

The leaves of some dismembered manuscripts were never used in portfolios but were distributed individually or in small groups, as gifts to friends or in small sales. Many portfolios are lost or have been broken up, their leaves sold individually. It is, however, usually possible to identify Ege leaves that aren’t in their original portfolios anymore, because of the distinctive mattes, inscriptions, or tape residue. Some of the manuscripts are themselves quite distinctive and easily recognizable, such as the late thirteenth-century Beauvais Missal.

This manuscript serves as a perfect example of just how great a loss is incurred when a codex is dismembered and its leaves scattered, but it also serves as a hopeful case study of the possibilities offered by recent developments in imaging and metadata standards, platforms, and interoperability. The Beauvais missal is a beauty, its numerous gilt initials with graceful, colorful tendrils extending into the margins easily recognizable. The manuscript was written in or near Beauvais, France around 1285 and was used early on at the cathedral there. We know this because of an inscription on a lost leaf, transcribed in a 1926 Sotheby’s auction catalogue. Peter Kidd recently discovered that the manuscript was purchased from Sotheby’s by none other than American industrialist William Randolph Hearst, who owned it until 1942 when he sold it through Gimbel Brothers to New York dealer Philip Duschnes, who cut it up and began selling leaves less than one month later. He passed the remnants on to Otto Ege, who scattered it through his usual means. The Beauvais Missal is number 15 in Ege’s “Fifty Original Leaves” set, but many leaves are known outside of his portfolios. I know of 92 leaves in permanent collections or that have come on the market recently, scattered across twenty-one states and five nations.

Unlike well-known leaves such as those from the Beauvais Missal, most of the 25,000 single leaves in North American collections are neither catalogued nor digitized. If metadata standards for the electronic cataloguing of manuscript codices are in flux, the standards for cataloguing leaves and fragments are truly in their infancy. It is not easy to catalogue manuscript leaves, as it requires expertise in multiple fields including paleography, codicology, liturgy, musicology, and art history, among others. But leaves are easy to digitize, much easier than complete codices. They’re flat, with no bindings to damage, no need to use weights to keep the book open during imaging. A digitized leaf can be put online with minimal metadata and made instantly available for crowd-sourced cataloguing and scholarly use. Many U.S. collections are beginning to do just that.

With this growing corpus of digitized leaves comes the potential to digitally reconstruct dismembered manuscripts such as the Beauvais Missal. I have heard skeptics ask why such reconstructions are worthwhile. Does the world really NEED another mediocre mid-fifteenth-century Book of Hours from Rouen? What do we gain from piecing Humpty Dumpty together again? It’s a reasonable question. Many of the books broken by Ege and his peers were not exactly of great art historical or textual import. Because they are manuscripts, however, every one is unique and worthy of study. I would argue that in many cases, such as the Beauvais Missal, the whole is much more than the sum of its parts. A lone leaf of the Beauvais Missal that preserves the liturgy for the feasts of a few Roman Martyrs in late July isn’t going to tell us much that we don’t already know. But identify the immediately preceding leaf that preserves a rare liturgy for St. Ebrulf of Beauvais on July 26, and we’re starting to get somewhere. The liturgy of Beauvais begins to come into focus alongside the music and the art historical record. Even reconstructing those shabby fifteenth-century Books of Hours serves a valuable pedagogical purpose, on top of any textual and art historical gain there may be; there is no better way to teach your students about the structure and contents of a Book of Hours than by having them piece one back together.

I know of at least three incipient projects that hope to reverse the scourge of biblioclasm:

Manuscript-Link at the University of South Carolina is a repository of siloed images submitted by multiple collections that will be catalogued by the project’s Principal Investigators. Registered users will be able to form their own collections online and compare multiple leaves side-by-side in parallel windows. [update: as of 2020, this project is defunct]

The international and recently fully-funded Fragmentarium project (organized by the team that brought you the splendid e-Codices site) will focus on the massive collections of binding fragments found in European national libraries, the market in whole, single leaves having been in many ways a predominantly American phenomenon.

Most promising for the North American corpus, I think, is the Broken Books project at St. Louis University. Broken Books will use a highly sustainable model in which holding institutions will be responsible for data and image curation. The Broken Books platform, according to the project’s website, will “allow the canvases that hold the digital images of the relevant leaves or pages to be annotated and arranged, so that users can attach annotations, including cataloguing metadata, to individual images or to a whole leaf, with the goal of virtually reconstructing the original manuscript.” The Broken Books platform will use Shared Canvas technology compliant with the International Image Interoperability Framework (IIIF), in which structural and descriptive metadata about a digitized object can be standardized and made interoperable.

In other words, instead of storing images and data on a dedicated server (by definition of limited capacity), the Broken Books tool will use persistent URLs to retrieve images when called for into a IIIF-compliant viewer such as Mirador, where they can be annotated and arranged by the user. This model is particularly sustainable, as it puts the onus of image and data duration on the holding institution, where it should be. Such interoperability also carries with it an expectation of Creative Commons licensing, which is, after all, the wave of the future.

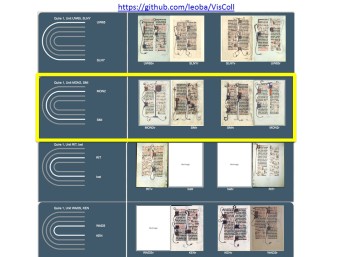

Imaging and data platforms are in development for all three projects and metadata standards are being established by teams of digital humanists, librarians, and manuscript scholars. For the purposes of such projects, the Ege leaves present a perfect test case. Working with the portfolios alone, it will be possible to easily reconstruct at least a portion several dozen Ege manuscripts. Using the Mirador viewer, Ben Albritton at Stanford University has just unveiled a case study that models how such digital reconstructions might work:

Albritton has reconstructed a portion of Ege’s “Fifty Original Leaves” MS 1 (a twelfth-century glossed Bible from Switzerland), comprised of leaves at Stanford, the University of South Carolina, the University of Mississippi, and others. The viewer uses PURLs to retrieve the images in the correct order when called for, pulling them into a IIIF-compliant viewer, in this case, Mirador. As an added bonus, the primary text has been transcribed using the T-Pen annotator (let’s hear it for interoperability!). Click on the speech bubble in the lower left corner of the viewer to see the annotations.

The Broken Books platform will function along similar lines and will also include metadata for each leaf. I’ve recently begun working with the Broken Books project, using the Beauvais Missal as a case study to help establish a metadata and authority structure. I hope to be able to debut the reconstruction using the Broken Books platform later this year.

In the meantime, there are several tools already in existence that can be used for this kind of work. I’m using an Omeka exhibit site as a workspace while the Broken Books platform is in development. The Omeka environment allows me to associate Dublin Core metadata with images of recto and verso in a single record and then easily put the leaves in their correct order. While this is a workable temporary solution, the Dublin Core metadata structure is somewhat inflexible and doesn’t really have room for all of the fields one would want in a full-scale Fragmentology project.

This is not a public site, by the way, because I do not yet have the rights to use some of these images for anything other than personal research.

I’m using a different tool to recreate the original bifoliate quire structure of the manuscript. Even though the Beauvais Missal has no foliation, reconstructing the signatures is possible because there are catchwords at the end of each quire. The gathering shown below was reconstructed using the Collation Visualization generator developed by Dot Porter at the University of Pennsylvania.

This brilliant tool combines a manuscript’s collation statement with PURLs of digital images to generate conjoint bifolia, as if the manuscript had been virtually disbound. I’m using the tool to reverse the process; once I know the order of leaves in a particular quire, I can use the Generator to digitally reunite formerly-conjoint leaves from disparate collections. For example, let’s look more closely at the second bifolium, outlined in yellow above. These leaves were originally conjoint, but are not consecutive.

The leaf on the left belongs to a private collector in Monaco, while its formerly conjoint leaf belongs to Smith College in Massachusetts. These two leaves haven’t seen each other since they were sliced apart in 1942.

So this is the situation in North America. We have more than 25,000 single leaves in several hundred collections. Some are beautifully digitized and skillfully catalogued. Others are catalogued incorrectly; some turn out to be printed facsimiles; others sit in a drawer, unknown and waiting. Digitization and metadata standards are still being established. We have our work cut out for us. But the promise of these projects is great. Historical circumstance has deposited a well-defined and cohesive corpus of leaves in the United States and Canada. Multiple leaves from dozens – perhaps hundreds – of manuscripts can easily be identified for reconstruction. We just need images and data, and a place to put them.

Thank you – what a fascinating story

Dear Linda,

thank you very much for your wonderful paper. I would like to add the importance of netbased dealing structures since the early 21th century. Platforms like Ebay and individual seller platforms have renewed the Ege phenomena. The new selling structuren enable sellers to find more clients for their sliced manuscripts. So a great market of individual buyers has emerged which is fed by destroying manuscripts. A lot of small collectors in the US bought such leaves.

Best greetings

Mark Mersiowsky

Thank you very much for this paper, and congratulations for the wonderful trip around American collections of manuscripts! As you perhaps know, the database Pinakes (http://pinakes.irht.cnrs.fr) and the network project Diktyon (http://www.diktyon.org/en) propose a list of Greek manuscripts around the world, as complete as we can, and persistent identifying numbers. Unfortunately, we are probably not up to date as far as USA are concerned, and especially for fragments and detached leaves. Maybe, a cooperation is possible?

Best,

Matthieu Cassin

Superb article; I learned a great deal and gained some links for the medieval manuscripts section of my Directory of Web Resources for the Rare Materials Cataloger (http://lib.nmsu.edu/rarecat/#MM). Thank you very much.

A wonderful article. Exciting to see this work progressing so well.

Pingback: Has the Age of Fragmentology arrived? | bonæ litteræ: occasional writing from David Rundle, Renaissance scholar

Pingback: The Age of the Fragment – Layers of Parchment, Layers of Time: Reconstructing Manuscripts 800 – 1600

Pingback: 11 Job Secrets of Paleographers - Top Normal