The Flight into Egypt, Walters Art Museum, MS W.188, f.112r

Most of the time, this road trip is virtual, an exploration of digitized manuscripts and their associated metadata and platforms in collections throughout North America. But sometimes I take an actual road trip, visiting medievalists at institutions and heritage sites far from my home in Boston to study their manuscripts in the flesh, as it were. Last week was one of those times. I spent two delightful days in Canada, visiting the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon and collection in a small private school three hours from there. These are among the northernmost pre-1600 European manuscripts in North America and, in the case of the school, some of the most remote.

Saskatchewan is the prairie of Canada, much like my home state of Oklahoma. Flat, big sky, beautiful serene scenery, windy, with glorious sunsets. Everyone I met was friendly and curious and eager to talk about and learn about the province’s medieval manuscripts. I was invited to Saskatchewan by Prof. Yin Liu and the University’s Classical, Medieval, and Renaissance Studies program, and I am very grateful to Yin and CMRS for the invitation and for the warm welcome.

Prof. Liu discussing Ege leaves with University of Saskatchewan students

My first stop was, of course, Special Collections at the University, where curator David Bindle had laid out a selection of manuscripts, early printed books, and facsimiles for a visiting class in Bibliography taught by English professor Lisa Vargo. The room was full of old friends (by which I mean VERY old), including the University of Saskatchewan’s Otto Ege portfolio, one of the rare and extraordinary “Fifty Original Leaves of Medieval Manuscripts” sets of which forty were produced and only twenty-eight have been located. No. 15 in the set is a leaf from my old and dear friend, the Beauvais Missal. It was a great joy for me to have the opportunity to speak to the students about Otto Ege and his impact on the American market in single leaves in the first half of the twentieth century (if Ege is new to you, you can read about him in several of my blogposts).

U. Saskatchewan students getting to know the Voynich Manuscript

And guess what I saw nestled among the shiny golden facsimiles of glorious late fifteenth-century French manuscripts made for nobility: the shy and smudgy and outwardly humble but extremely detailed and accurate Siloé facsimile of the Voynich Manuscript! Naturally, I had to invite the students to come over and take a look as I walked them through the mysterious manuscript’s history and contents. An added and unexpected treat!

After the class, I had lunch with a group of faculty and students, mostly from the English department, many of whom were working with Profs. Barbara Bordalejo and Peter Robinson on the massive and long-term Canterbury Tales project. Robinson has been working on the project for decades with the goal of transcribing all of the known manuscripts of the Canterbury Tales and using computer algorithms to analyze the variants among the manuscripts to refine the received wisdom about the transmission of Chaucer’s work. Hundreds of students have worked on the transcriptions over the years as the project has migrated through various formats. Currently, the transcriptions are encoded using the Text-Encoding Initiative, with customized tags and a custom backend that uses IIIF-compliance to display images alongside the TEI transcription. Check out the project website for more details!

The original plan had been for me to head back to Special Collections after lunch to spend some time with the Library’s codices, but after Prof. Robinson and Prof. Bordalejo invited me to visit the Canterbury Tales Project workroom, I couldn’t resist the chance to be in the room where it happens. They even went so far as to set up an account for me so that I can participate in the transcription and encoding.

Univ. of Saskatchewan MSS 14.1 (the “Brendan Missal”), f. 98v. The red circle circumscribing a Greek cross is an “osculatory target.”

My time was limited, so after an hour or so Yin walked me over to Special Collections where I spent some time with this early fifteenth-century Missal recently purchased by the University. Although the codex is lacking several dozen leaves, it includes enough evidence to provide a rough localization to the Low Countries. One piece of this evidence is a fascinating later addition on the opening leaf, an inventory of the treasures of an “Altar of St. Brendan” written in Dutch and Latin that is most definitely worthy of further study. Line 5 of the inventory records a “Misboeck op perghemynte ghescreven” (“a Massbook written on parchment”) that may refer to this very codex. The inventory is witnessed by the notary Bernardus tor Schuren and is dated 1532. In the original portion of the manuscript, the Canon and the mass for Easter each include a fascinating detail, roundels in the bottom margin in red and orange encircling a Greek cross. These are almost certainly “osculatory targets,” meant to be kissed by the Priest as a sign of veneration.

But I wasn’t in Saskatchewan just to look at the books. That evening, I delivered the opening lecture of the CMRS annual colloquium series. The title of my presentation was “Scattered Leaves and Virtual Manuscripts: The Promise of Digital Fragmentology,” essentially a history of the study of fragments and the development of efforts to digitally reconstruct dismembered manuscripts. The lecture was well-attended with a lively discussion afterwards and a show-and-tell of Otto Ege leaves on display. My thanks to curator David Bindle for facilitating the display of Ege leaves.

Off on a road trip with Yin at the wheel!

The highlight of my trip took place the following day when I embarked on the ultimate manuscript road trip, driving deep into the plains of Saskatchewan to visit a small private collection of rare books and manuscripts at Athol Murray College of Notre Dame in Wilcox. This was, without doubt, the most remote collection I have visited in North America. We were two carloads of eager explorers: Yin and myself, Prof. Courtnay Konshuh, and three students (Tristan, Amanda, and Chloe). We drove through the rural towns of Craink, Moose Jaw, and Rouleau (familiar to Canadians, I’m told, as the fictional town of Dog River in the popular Canadian television show “Corner Gas”) before reaching our destination, the small railside town of Wilcox three hours from Saskatoon. The collection belongs to a small Catholic boys’ school founded in 1920 and now best known for its hockey team, although its extraordinary rare book collection should certainly put it on the map.

When we arrived, we were greeted by the archivist, who gave us a brief tour and introduction. The rare book collection is part of a museum dedicated to the history of the school and its founder, Father Athol Murray. Several relics of Father Murray’s life are part of the collection, including his old suitcase and scarlet vestments. The books came to Father Murray from several different sources; some were bequeathed by his father or other family members, others were gifted by friends or devoted students. For example, his copy of the Nuremberg Chronicle

The Nuremberg Chronicle

was a gift from a group of former students. According to the story, Father Murray – a Catholic Priest – had been saving his money to buy the volume but when he learned that a student was in need, he used that money to help the student instead, in what was clearly a typical act of generosity for the man commonly and lovingly known as Père. When the word spread of his decision to reallocate the money he had saved, a group of former students banded together to buy the Chronicle for him.

The collection was catalogued in 2003 by University of Saskatchewan student Michael Santer, as his Master’s thesis. The catalogue’s introduction serves as a biography of Father Murray, while the catalogue is focused on the printed books and their provenance. It was the appendix that caught my eye: the manuscripts. Santer worked with several University of Saskatchewan professors to create a handlist of the handful of manuscripts in the collection. In addition to several documents, the collection includes three incomplete but interesting codices: a thirteenth-century manuscript of the Legenda Aurea (Jacobus de Voragine’s Golden Legend, a lengthy collection of saints’ lives that was extremely popular throughout the Middle Ages); a late thirteenth-century collection of the Decretals of Pope Gregory X; and what appeared at first glance to be a late-twelfth or early-thirteenth-century fragmentary manuscript of several saints’ lives.

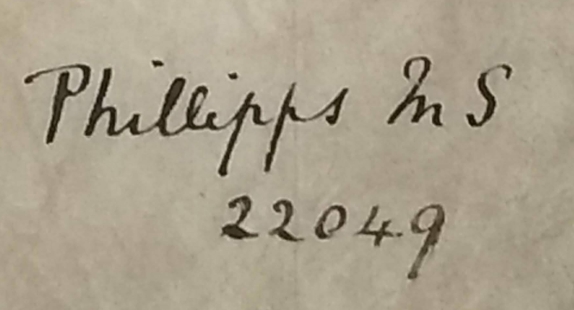

In its current state, the latter codex includes extracts from the Life and Miracles of St. Martin of Tours (attributed to the fourth-century French chronicler Sulpicius Severus) and the Lives of the Seven Sleepers (a Rip van Winkle-esque saga spuriously attributed to Gregory, Bishop of Tours) (Bibliotheca Hagiographica Latina no. 2320; for the full text, see Patrologia Latina 71:1107B-1110C). The manuscript has an esteemed provenance: at the bottom of the first flyleaf is the signature and shelfmark of none other than Sir Thomas Phillipps (1792 –1872), arguably the most prolific collector of all time, a man who has made his way into this blog several times.

In its current state, the latter codex includes extracts from the Life and Miracles of St. Martin of Tours (attributed to the fourth-century French chronicler Sulpicius Severus) and the Lives of the Seven Sleepers (a Rip van Winkle-esque saga spuriously attributed to Gregory, Bishop of Tours) (Bibliotheca Hagiographica Latina no. 2320; for the full text, see Patrologia Latina 71:1107B-1110C). The manuscript has an esteemed provenance: at the bottom of the first flyleaf is the signature and shelfmark of none other than Sir Thomas Phillipps (1792 –1872), arguably the most prolific collector of all time, a man who has made his way into this blog several times.  This is Phillipps MS 22049, acquired by Phillipps in the late 1860s (see Munby, A. N. L., The Formation of the Phillipps Library Between 1841 and 1872 (Phillipps Studies No. IV), p. 208) and sold from the collection at Sotheby’s on 6 June 1898, lot 841. It’s not clear when Father Murray acquired the manuscript, but it was likely in the early decades of the twentieth century.

This is Phillipps MS 22049, acquired by Phillipps in the late 1860s (see Munby, A. N. L., The Formation of the Phillipps Library Between 1841 and 1872 (Phillipps Studies No. IV), p. 208) and sold from the collection at Sotheby’s on 6 June 1898, lot 841. It’s not clear when Father Murray acquired the manuscript, but it was likely in the early decades of the twentieth century.

At first sight, I ascribed the manuscript to early thirteenth-century France based on the style of the script and the gorgeous, elaborate red and purple penwork.

Initial [T], The Lives of the Seven Sleepers (f. 21)

The manuscript is fragmentary, currently consisting of only twenty-two leaves. A French manuscript from the thirteenth-century should be constructed of quaternions, signatures made up of four nested bifolia, i.e. eight leaves. These twenty-two-leaves, however, are comprised of a quire of twelve (with at least one bifolium missing, so originally at least fourteen) and a quire of ten. This format is EXREMELY unusual in northern Europe, especially in the thirteenth century. So I did what I always do when I have a difficult manuscript problem. I turn to Twitter, #MedievalTwitter in particular. I posted an image of the manuscript and within minutes was engaged in a conversation with paleographers from both sides of the Atlantic. In the end, expert paleographer Erik Kwakkel suggested that the manuscript was likely written in the fourteenth-century by a scribe attempting to imitate an earlier script, something that, while not exactly common, is not unheard of. We cannot know if the archaizing script was intended to deceive or to pay homage. Modern forgers, such as the Spanish Forger, are usually in it for the money. Our late-medieval scribe, on the other hand, may have been copying an older manuscript or simply practicing a different kind of script than the one he was used to. There is much more to learn about this lovely manuscript, including piecing together its journey from France to Phillipps to Sotheby’s to Saskatchewan.

As we drove back to Saskatoon, dazzled by a blazing prairie sunset, we found ourselves wondering what Sir Thomas Phillipps would have thought about the fate of his MS 22049. I suspect he would have been puzzled at first (after all, the province of Saskatchewan didn’t exist until just a few years before his death). But as a collector himself, Phillipps would certainly have appreciated that the manuscript had found a happy home, first in the hands of the students’ beloved Père and now in the collection of the school he loved.

As we drove back to Saskatoon, dazzled by a blazing prairie sunset, we found ourselves wondering what Sir Thomas Phillipps would have thought about the fate of his MS 22049. I suspect he would have been puzzled at first (after all, the province of Saskatchewan didn’t exist until just a few years before his death). But as a collector himself, Phillipps would certainly have appreciated that the manuscript had found a happy home, first in the hands of the students’ beloved Père and now in the collection of the school he loved.