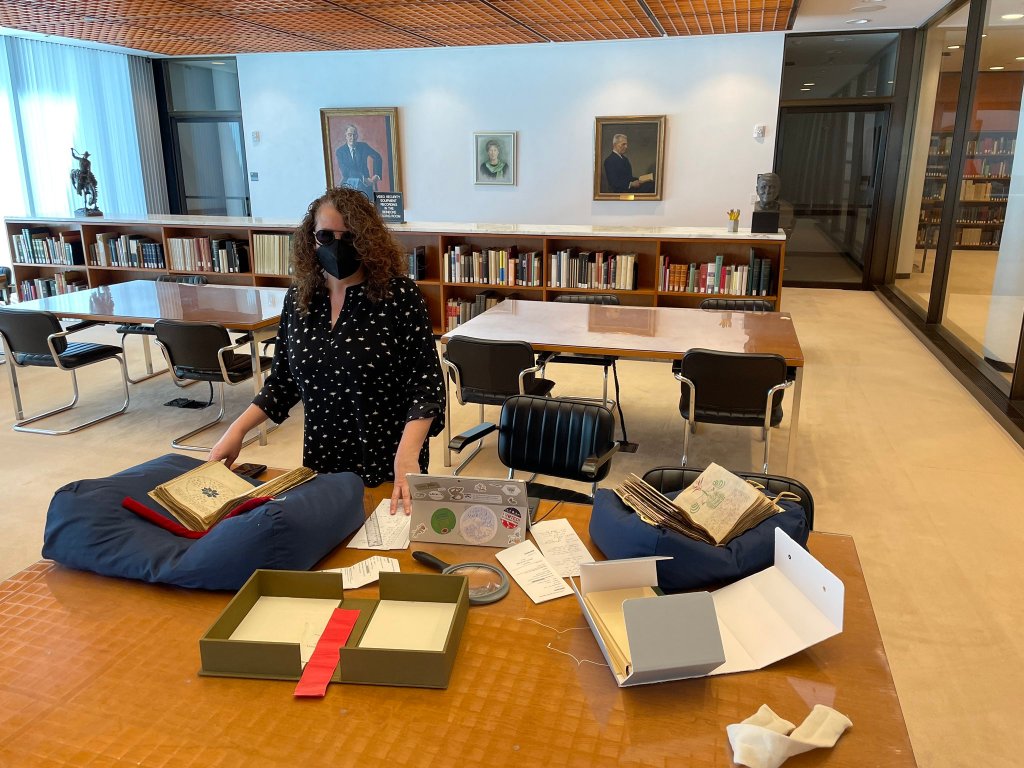

As we begin to make our way out of the COVID-19 pandemic, it isn’t only restaurants and theaters that are opening up. Libraries, too, are reopening to the public, and Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library is no exception. After several years of restricted access and closures, the Beinecke is now open for outside researchers, albeit with masks and proof of vaccination required. The Beinecke is one of my favorite places to visit, and when I heard that the Library would be welcoming outside researchers as of April 11, I made my plans right away, securing authorization to visit the campus and permission to spend April 22 with none other than MS 408, a.k.a. The Voynich Manuscript.

It’s a two-and-a-half hour train ride from my Boston home to New Haven, Connecticut. A 6 AM train would ensure that I reached the Library right when it opened, giving me as much time as possible with the manuscript. After arriving in New Haven and Ubering to the Library, it took just a few minutes to confirm my authorization with the Library guard, put my bag away, and check in with the service desk. And then I could get to work.

You might be wondering why I felt I needed to see the Voynich Manuscript in person, since the Beinecke’s website provides hundreds of high-resolution images in an open-access environment. For most purposes, the online images are more than sufficient. And as thrilling as it is to handle such an important and ancient object, there are lots of reasons NOT to, including the need to protect it from over-handling and environmental exposure. That’s why I’ve had to get special permission to see the manuscript each time I’ve studied it in person (and if you want to know why I’m not wearing white cotton gloves, check out this blogpost from the experts at the British Library).

This is my sixth time studying the Voynich Manuscript in person, and I feel very fortunate to have had those opportunities. For the work I’m doing – studying the relationship between the work of each of the five scribes and the codicological features of the manuscript – in-person examination is critical. I need to study the quire structure, the binding, and the sewing – the three-dimensional components of the manuscript. By exploring the collaborative nature of the crafting and writing of this manuscript, we come one step closer to understanding its origins. These codicological features can’t always be discerned in digital images; hence, my visit to the Library.

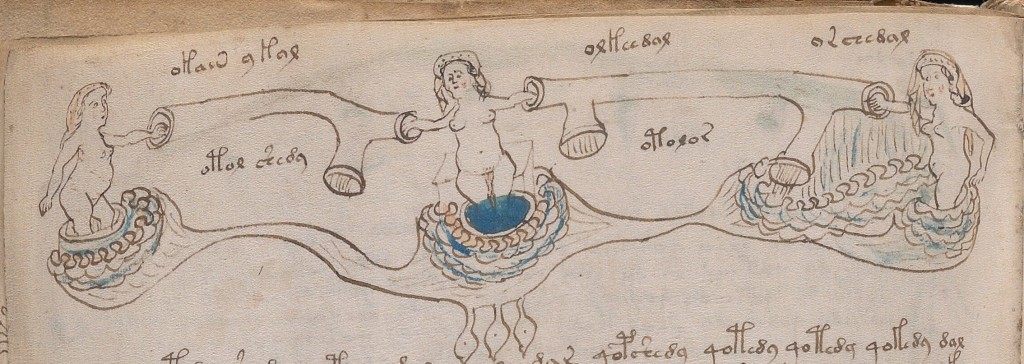

The high-resolution images on the Library’s website are also critically important for my work, as they facilitate a detailed examination of this unique writing system. But even images like these don’t always capture the paleographic features I’m looking for. For example, it’s hard to tell for sure the sequence of writing for the complex glyph found on the first line of folio 42 recto (shown at left). Looking at it in person, though, I can tell that the dark curved line was clearly written on top of the vertical line, rather than the other way around. This tells me something interesting about what’s happening here. After the original glyph was written, someone – probably one of the scribes – amended or corrected the glyph by adding the curving stroke. This, in turn, sheds light on the process of writing the manuscript. If someone was correcting or editing the text after it was written, that adds to the evidence that there is in fact meaningful text underlying these mysterious glyphs – text that several people (at least five by my count) knew how to read and write – and that one of those people had editorial authority.

Here’s another example. The gutter of the fold-out that comprises folios 71 and 72 (above) is fragile and has been re-enforced by a strip of modern vellum to protect it from tearing (red arrows above). Unfortunately, that strip obscures some of the text in the online image of f. 71v (detail below left, rotated 90° counter-clockwise). I was able to image a bit more of the hidden text yesterday (detail below right).

The same is true on f. 102r (left), where a crease in the parchment has obscured some of the glyphs in the online image. My image captures some of the hidden glyphs.

These images represent just a few of the outcomes of yesterday’s research trip. I took hundreds of high-magnification images that will help me further understand the writing system and the distinctive characteristics of the various scribes.

Why should those few extra glyphs matter? And why does it matter how many scribes there are and how they collaborate across the manuscript? Because in order to make any progress understanding what (if anything) this manuscript has to say, linguists, cryptologists, and computational analysts need data, and every bit of data helps. I’m not trying to “decode” the manuscript myself – I am not a linguist, or a cryptologist, or a data analyst. I am a paleographer and a codicologist, applying my thirty-years of experience studying hundreds of medieval manuscripts to the conundrum that is the Voynich Manuscript. I hope that my work will help facilitate the work of others and that interdisciplinary collaboration will eventually lead to understanding.

In that spirit of interdisciplinarity, I’ve been collaborating for more than a year with a group of linguists, cryptologists, and experts in computational analytics – most of whom are affiliated with the University of Malta – all of us bringing our particular skillsets to the problem of making sense out of the Voynich Manuscript. As the only humanist in the Zoom Room, my role in this working group is to represent the manuscript itself, to advocate for the object and its objective reality. As a paleographer, my expertise is in the graphic properties of Voynichese. As a codicologist, I’m there to remind my colleagues about the unusual structure of the manuscript and ensure that they take into account the implications of both structure and writing system in their linguistic and computational analyses (for an introduction to these properties and some basic linguistic analyses, see this video interview with myself and Yale University Professor of Linguistics Claire Bowern, or read my recent article in Manuscript Studies).

Several members of this working group (including myself) will be presenting new research at an upcoming Voynich conference, taking place online from 30 November to 1 December, 2022. For more information and to attend (or to submit an abstract for consideration), click here.

We hope to “see” you there!