Like all of us, I’ve been working and teaching from home for nearly a year, waiting with bated breath for the vaccine distribution, wearing my mask to keep myself and my community safe, and working exclusively from digital images of medieval manuscripts. My recent appointment as a lecturer in Latin Paleography at Yale meant that when libraries on campus opened to faculty and students I was allowed to, at long last, visit an actual library to do some research with real, not digital, medieval manuscripts. And not just any library, but the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale, where I first catalogued and studied medieval manuscripts in earnest while in graduate school there in the early 1990s.

Because the pandemic is still raging in the U.S., my class meets remotely, like most university classes in the U.S. this semester. Since the Beinecke has digitized hundreds of manuscripts in recent years, I am able to teach a survey of Latin Paleography with reference to those images. And with the launch just last week of a new IIIF-compliant digital viewer at Yale, discovering, browsing, and sharing those images just got a whole lot easier. But digital images, while extremely useful for paleographers thanks to deep zoom and interoperability, aren’t sufficient if you also want to study codicology, that is, the structure of medieval manuscripts. You have to get your hands on the books. Paleography isn’t just about the letters written on the paper or parchment. It’s also about context, what Leonard Boyle called “integral paleography.” It’s about the substrate, the ink and pigments, the decoration, the format, the construction of bifolia, quires, and binding and, ultimately, the institutional context within which the manuscript was written and read, whether monastic, secular, or professional, and its journey from there-and-then to here-and-now. And so I wanted to find a way to give my students, some of whom are Zooming in from overseas, a way to engage with the three-dimensional multi-sensory experience of the medieval codex. Hence my day at the Beinecke, surveying manuscripts that will be made available to my students, on appointment, to study onsite (for my overseas students, I’ve found local collections for them to visit).

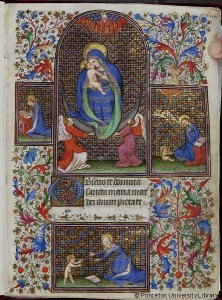

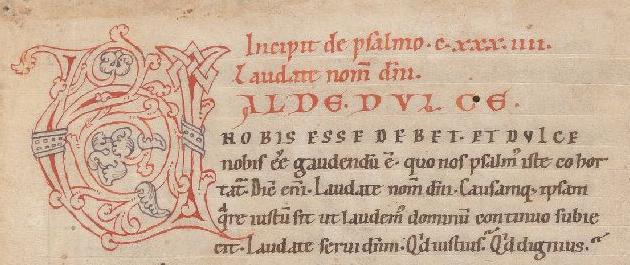

I spent time with an old friend that day, MS 699, the fifth of a five-volume set recording Augustine’s Enarrationes in Psalmos, written in Lambach, Austria, in the third-quarter of the twelfth century. Why is it an old friend? Because it played a significant role in my PhD thesis and first book, The Gottschalk Antiphonary: Music and Liturgy in Twelfth-Century Lambach. MS 699 was illustrated by the same Gottschalk who illustrated, wrote, and notated the eponymous antiphonal (a manuscript that was recycled for binding use at Lambach in the fifteenth century and that I recently reconstructed online here). Multiple scribes worked on these Augustine volumes, but the four extant volumes of the set were all illustrated by Gottschalk of Lambach:

Clockwise from top: initials by Gottschalk of Lambach in Vol. I, Vol. II, Vol. IV, and Vol. V (i.e. Beinecke MS 699) of Augustine’s Ennarationes in Psalmos (Vol. III is lost. Image from Vol. I taken from Holter 1993, p. 435, fig. 19)

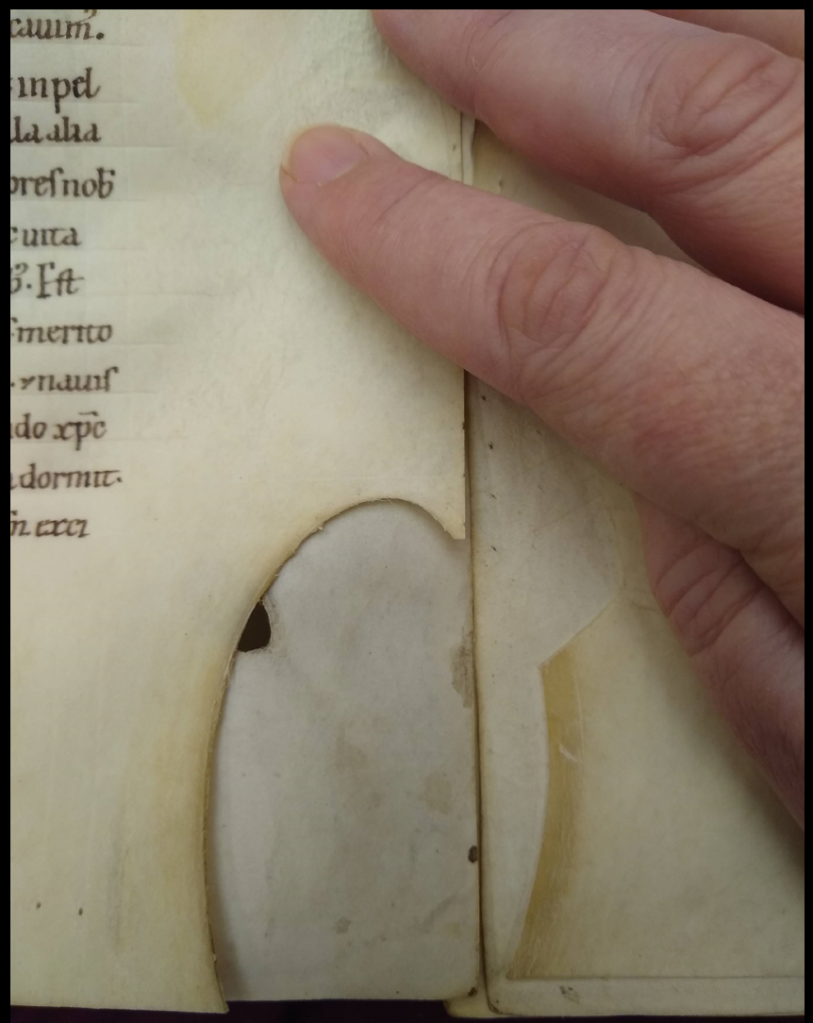

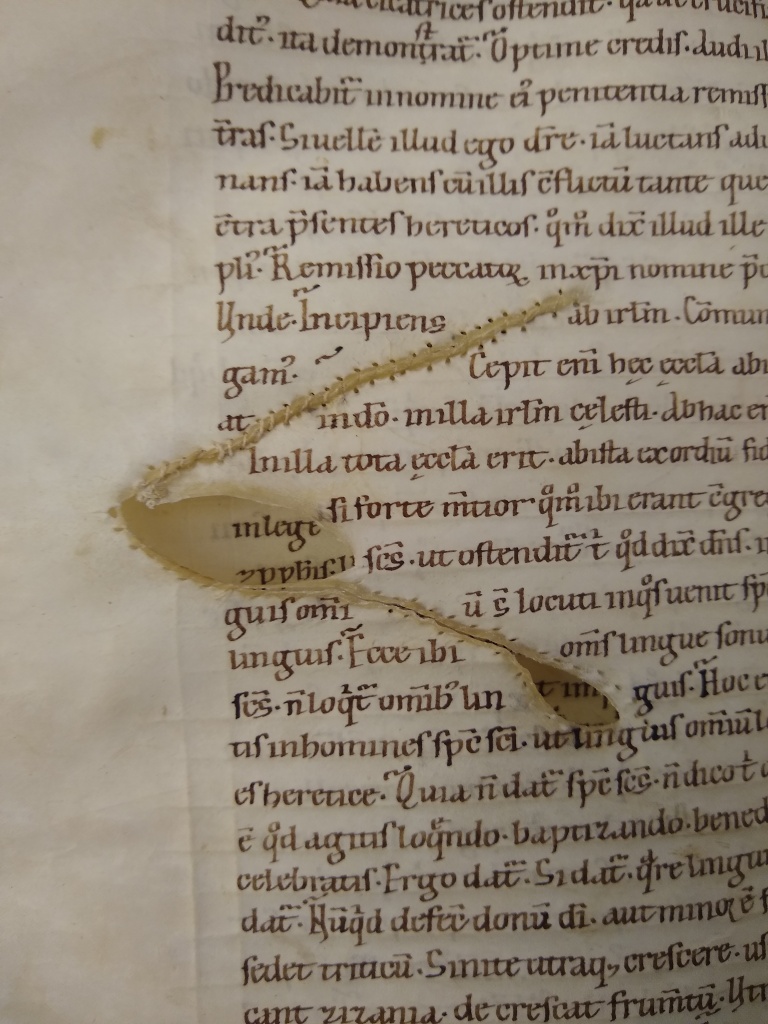

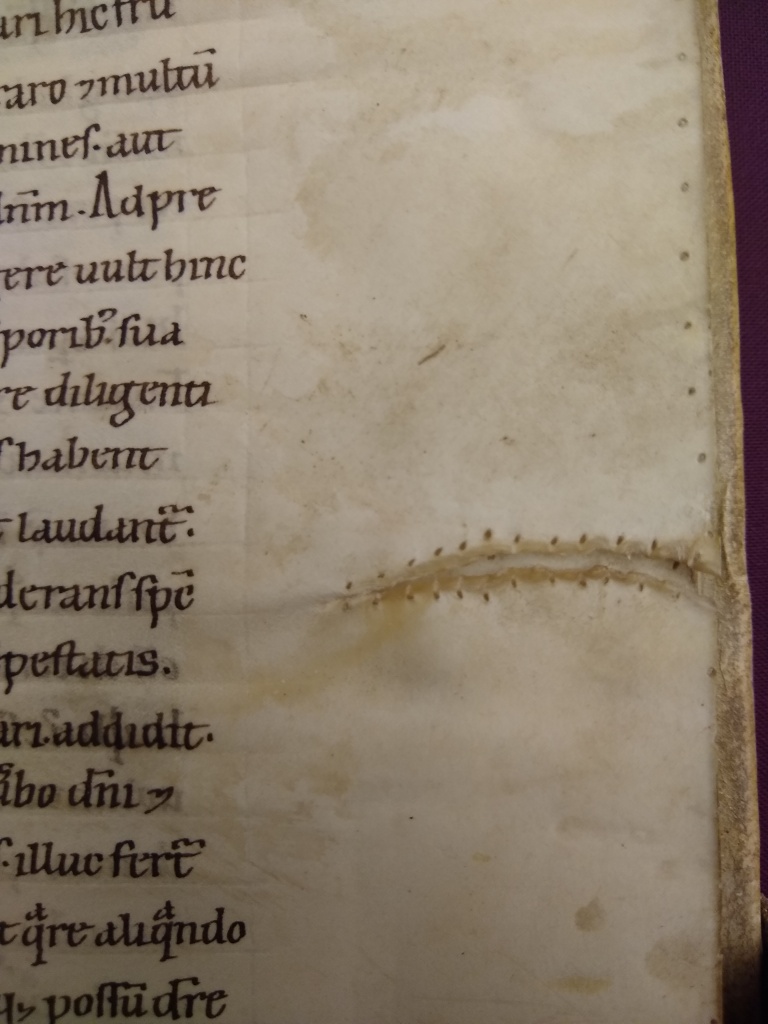

MS 699 is a perfect example of a typical 12th-c. monastic manuscript in its size, layout, script, decoration, use of signatures (at the end of each quire in Roman numerals), the original incised pigskin binding, and the quality of the parchment. Don’t get me wrong, the Lambach monks were very skilled when it came to making parchment. You can easily distinguish hair-side from flesh-side, both by color and by texture. The quires are arranged according to “Gregory’s Rule,” with hair-side facing hair-side and flesh-side facing flesh-side, giving a consistent color and texture across each opening. The parchment is supple and smooth, perfectly prepared to receive the iron gall ink. But the monks were frugal. Instead of cutting around flaws in the skin to create blemish-free bifolia, they used all of the skin available to them, flaws and all. The leaves are full of holes, tears, and slits, whether from natural processes like bug bites or scarring from when the animal (presumably a sheep) was still alive, or tears inflicted by the parchmenter during scudding or stretching. These flaws are why I wanted my students to see this manuscript in person.

Parchment flaws in MS 699

One of the things I find most engaging about working with medieval manuscripts is the palpable connection they provide to the past. When I’m turning the pages of a manuscript like MS 699, I’m imagining the butcher, the parchmenter, the scribe, the artist, the binder, and hundreds of years of readers and owners who’ve handled and read the codex. I’m walking its path from 12th-century Lambach to 21st-century New Haven. While studying the manuscript in person this time, though, I was able to take it back another step, to literally start piecing together the manuscript’s first journey, from sheep to parchment to bifolia, by reverse-engineering the codex.

It’s sometimes easy to forget that parchment is an animal’s skin. It has an outside (the hair side, yellowed and rough) and an inside (the flesh side, light and smooth). The size of the codex depends on the size of the bifolia cut from the skin, which in turn depends on the size of the skin itself, which in turn depends on the size of the animal. I’ve seen giant choirbooks in which each folio is an entire skin, with the spinal column running vertically down the middle. That skin-sized single sheet might be folded in half to create one bifolium. During the 12th century, when monastic textual manuscripts tend to be around 350 x 250 mm, it was typical for a skin to be cut into four bifolia. This diagram shows how that might happen, using the bibliographic terms folio, quarto, and octavo (two sheets, four sheets, and eight sheets):

Handmade Paper Method Cinquecento:

Renaissance Paper Textures

(Oakland, CA: Magnolia Editions, 2018),

p. 20, fig. 2

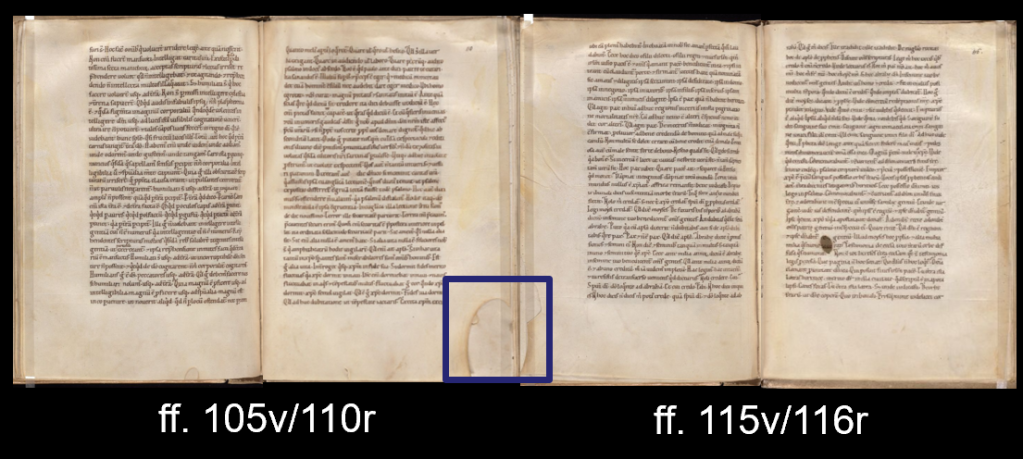

Because there are so many flaws in these leaves, I had hoped that I might be able to find evidence of how the bifolia were cut from the skin. After carefully scanning the outer edges of each leaf, I found two whose edges fit together perfectly, showing exactly how the knife cut them from the skin. The edges of f. 110 and f. 115 fit together like puzzle pieces, which is exactly what they are.

The two bifolia (ff. 105/110 and ff. 115/116) were originally connected at their short edges, as shown below.

When together, they must have spanned the length of the skin. This means that the monks who cut the skin into bifolia were cutting four bifolia from each skin. Each leaf is 195 x 227 mm. Each bifolium is 390 x 227. The usable portion of the skin, then, measured around 780 x 454 mm, or 30 3/4 x 18 3/4 inches, a fairly typical size for a sheepskin. And now we can even partially reconstruct the very sheepskin from which these two bifolia were cut:

I haven’t yet been able to find evidence of the other two bifolia cut from this skin. Because I haven’t found the missing lower part of the hole in any other bifolium of the manuscript, I’ve oriented the two bifolia so that the flaw was close to the outer edge of the skin rather than the spine.

So now we’ve made our way backwards from 21st-century New Haven to 12th-century Lambach, all the way back to the parchmenter’s workspace at the Lambach Abbey. Now let’s see what else we can learn about book production in Lambach by moving forward in time just a bit.

The five-volume set of Augustine’s Enarrationes in Psalmos was an enormous project, requiring hundreds of bifolia in all:

Volume I (Psalms 1-50): Codex membranaceus lambacensis XVII (now Leutkirch, Fürstlich Waldburgschen Gesamtarchivs MS 5). 216 leaves = 108 bifolia = 27 skins

Volume II (Psalms 51-100): CML XVIII (sold at Christie’s in 2000, then by Les Enluminures to a private European collection). 279 leaves = 140 bifolia = 35 skins

Volume III (Psalms 101-117): CML IX (lost, number of leaves unknown)

Volume IV (Psalms 118-133): CML LXV (now Frankfurt, Stadt- und Universitätsbibliothek Lat. qu. 64). 192 leaves = 96 bifolia = 24 skins

Volume V (Psalms 134-150): CML LXIV (now Beinecke MS 699). 141 leaves = 71 bifolia = 18 skins

In all, well over 100 sheepskins. That’s a lot of sheep and a lot of labor.

These volumes are constructed like most 12th-century Germanic monastic manuscripts, in quires of four nested bifolia. The bifolia were assembled and slip-stitched together to make a quire for writing. After the manuscript was written and illustrated, the quires were stacked in order, sewn together on cords perpendicular to the spine, and secured between wooden boards covered with leather. The first step in the writing process is for a scribe to walk over to the pile of prepared parchment and pick out four bifolia to work with. You might assume that two bifolia cut from the same skin would end up together in the pile. They might, then, be grabbed by our monk as he assembled his quire and end up close together, if not consecutive, in the final codex. In this case, however, the bifolia are separated by several sheets:

Bifolium 105/110 is the second bifolium (i.e. the 2nd and 7th leaves) of the fourteenth quire of MS 699. Bifolium 115/116 is the central bifolium (i.e. the 4th and 5th leaves) of the next quire, the fifteenth. These two bifolia, cut from the same skin, ended up near one another in the codex, but in different quires. This suggests either that somewhere in the process the bifolia were separated in the pile, or that the monk who chose the parchment for his work put some judgement into selecting bifolia for each quire, rather than just grabbing the four at the top.

Reverse-engineering the codex has brought us from my hand turning the leaves in New Haven in the year 2021 past 850 years of readers to the Lambach bindery, scribe, artist, parchmenter, and butcher, all the way back to a lone sheep grazing along the River Traun near the Lambach Abbey around the year 1175.

Thanks, sheep.

Bibliography:

Holter, K. “Initialen aus einer Lambacher Handschrift des 12. Jahrhundert (Ms. 5 des Fürstlich Waldburgschen Gesamtarchivs in Schloß Zeil in Leutkirch)” Wiener Jahrbuch für Kunstgeschichte 46-47 (1993-4): 255-265, 443-436.

When I first studied the Gottschalk Antiphonal in the early 1990s, I did it with scissors and paste and black-and-white photocopies on the floor of my living room. It is truly thrilling to see it in glorious IIIF-compliant interoperable color in Fragmentarium. I hope that the reconstruction will complement the liturgical, art historical, and musicological study in my book, bringing this beautiful example of twelfth-century music, liturgy, and decoration to a new generation of students and scholars.

When I first studied the Gottschalk Antiphonal in the early 1990s, I did it with scissors and paste and black-and-white photocopies on the floor of my living room. It is truly thrilling to see it in glorious IIIF-compliant interoperable color in Fragmentarium. I hope that the reconstruction will complement the liturgical, art historical, and musicological study in my book, bringing this beautiful example of twelfth-century music, liturgy, and decoration to a new generation of students and scholars.