The Flight into Egypt, Walters Art Museum, MS W.188, f.112r

An appropriate subtitle for this blog would be “Medieval Manuscripts in Unexpected Places.” Today’s installment is no exception.

The whaling town of New Bedford is nestled on the New England shore of the North Atlantic, in southeastern Massachusetts. It is an important center for the history of the whaling industry in New England, and its beautiful Public Library includes more than a century’s worth of whaling logs and records. But it also includes something much older, a sumptuous Book of Hours from France written around the year 1465.

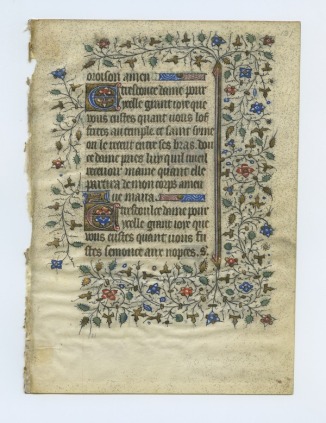

This 98-leaf manuscript is a real beauty, with nine miniatures and five full borders:

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

This manuscript has never been studied or widely noted before now. It was recently brought to my attention by Phil Weimerskirch, the retired librarian of the Providence Public Library. Phil is 87 years old, and for nearly twenty years has been an important source of local knowledge for myself and my colleague and co-author Melissa Conway as we compiled our Directory of Collections in the United States and Canada with Pre-1600 Manuscript Holdings. During his career in Providence, Rhode Island, Phil – who is an expert bibliographer and book historian – regularly explored small collections throughout southern New England looking for unrecorded medieval manuscripts. At last count, he had brought more than a dozen such repositories to our attention. He remains, by far, our greatest sleuth and for his knowledge and experience we are extremely grateful!

When Phil emailed me a few weeks ago to confirm the presence of this manuscript in New Bedford, he included a few images. I could tell immediately that this manuscript was something special (not that they aren’t ALL special in their own way), not your every-day run-of-the-mill manuscript. Janice Hodson, the Library’s Art Curator, welcomed me to the collection last week to study and photograph the manuscript and has graciously given me permission to share my photographs and findings here.

I’m going to use this post as an opportunity to walk you through the steps of researching Books of Hours, and I will include links to several important online resources of particular use when working with such manuscripts. Roger Wieck’s Time Sanctified remains the best printed introduction to the genre, and I highly recommend you purchase it if you are going to work with Books of Hours in any capacity. If you’d rather explore an online primer, Les Enluminures presents a profusely illustrated introduction to Books of Hours here.

The first thing to know is that Books of Hours were personal prayerbooks, as opposed to books for use in a church or cathedral (the Beauvais Missal is one such churchbook). As such, they were not in general produced by monks or nuns in abbey scriptoria but were written and illuminated by professionals often working on commission. The genre developed in the mid-thirteenth century but really took off with the establishment of professional centers of book production in the fifteenth century. Wealthy patrons commissioned these prayerbooks for their own home use and could request personal touches such as added devotions to their name-saint or to saints of local importance, even self-portraits or coats-of-arms. In addition, particular sections of the liturgy can vary by locale. Books of Hours, therefore, are full of clues as to their origin and patronage. You can even tell if a book was made for the use of a woman, as many Books of Hours were.

As far as contents are concerned, Books of Hours are modular, consisting of discreet sections usually presented in the same sequence, although not all Books of Hours include all of these sections or present them in this order:

Liturgical calendar (listing which saints are to be commemorated on which day)

Passion narratives from the Gospels (often illustrated with portraits of the evangelists at work)

The Hours of the Virgin (divided into the eight canonical offices of the day, each of which is often illustrated with a scene from the life of the Virgin Mary): Matins (the Annunciation), Lauds (the Visitation), Prime (the Nativity), Terce (the Annunciation to the Shepherds), Sext (the Adoration of the Magi), None (the Presentation in the Temple), Vespers (the Slaughter of the Innocents or the Flight into Egypt), and Compline (the Slaughter of the Innocents, the Flight into Egypt, or the Coronation of the Virgin).

The Hours of the Cross and the Hours of the Holy Spirit (illustrated by the Crucifixion and Pentecost respectively and often abbreviated, in which case called “Little” Hours)

Prayers to the Virgin Mary (“Obsecro te” and “O intemerata”)

The Penitential Psalms (a group of seven Psalms – 6, 31, 37, 50, 101, 129, and 142 – that focus of the theme of repentance, usually accompanied by a portrait of King David or a scene from his life) and Litany (a series of Saints grouped by type and gender – Apostles, Popes, Martyrs, Virgins, etc. – from whom the penitent requests intercession)

The Office of the Dead (illustrated by a funeral, burial, or a scene from the Book of Job)

Suffrages and additional prayers (optional prayers for particular saints or events, sometimes illustrated by portraits of the particular saints)

When faced with a Book of Hours, the first step is to identify the contents and determine if anything obvious is missing or is out of order. Then you can go through more carefully looking for clues.

While conducting my initial survey, I could see that something was wrong. There were only five miniatures in the Hours of the Virgin instead of the expected eight. A comparison of the text with the online Hypertext Book of Hours confirmed that several sections of the Hours of the Virgin were missing: the end of Terce, the beginning and end of Sext, all of None, and most of Vespers. In addition, the Office of the Dead was interrupted twice, by the Hours of the Cross and by the Hours of the Holy Spirit. Sometimes the Hours of the Cross and the Hours of the Holy Spirit are inserted into the middle of the Hours of the Virgin (the term is “intercalated”), but never into the Office of the Dead. Clearly something was out of sequence here as well.

I set the codicological issues aside and began working on identifying the liturgical use of the manuscript, that is, identifying the place for which it was made. This is often different than the place in which it was made.

Stylistically, the manuscript can be localized to northern France, possibly Rouen, and dates to around 1460-70. In private correspondence, art historian James Marrow observed that the illumination style is similar to the workshop of the Masters of the Échevinage de Rouen, a workshop active in Rouen and the Loire Valley in the third quarter of the fifteenth century. If you compare the New Bedford Hours Annunciation miniature (below left) with the Annunciation in British Library Sloane 2732 B (below right, also attributed to the Masters), you can see the resemblance in the composition, the setting, and the treatment of hands and faces, even the structure of the Angel Gabriel’s wings and the gold cross-hatching that gives texture to the drapery.

New Bedford Hours, f. 29 v

British Library, Sloane 2732 B, f. 14 detail

Even if you’re not an art historian, you can at least get a sense of the date of the manuscript simply by looking at the border illumination. In the early fifteenth century, borders are comprised of delicate spindly vines (“rinceaux”) and small gold trefoil leaves. As the century progresses, colorful thick foliage begins to appear in the corners (“acanthus leaves”).

f. 13

By the third quarter of the century, the acanthus leaves have overtaken the rinceaux, as in this manuscript. By the end of the century, they’ve forced the rinceaux completely into the background and have come to dominate the border decoration.

So the manuscript was made in northern France, possibly Rouen, around the year 1465. But for WHOM was it made? To answer that question, we have to conduct a detailed textual investigation of several sections of the manuscript: the calendar, the Hours of the Virgin, the Litany, the Office of the Dead, and the suffrages.

Liturgical calendars such as the one in this Book of Hours are universal, as opposed to year-specific, and indicate which saint is to be commemorated on which day (they also help you determine the date of Easter and which days are Sundays in any particular year, but that’s another story). Saints are presented in a hierarchy indicated by color: saints in black ink are of “normal” importance, while those in red are more so (hence the expression “red-letter day”).

The first half of September in the New Bedford Hours, with the Nativity of the Virgin Mary in blue and the Exaltation of the Cross in red (f. 9)

Some calendars give a third level of importance, indicated by blue or gold ink. In the present manuscript, saints are written in black, red, and blue, with the latter reserved for the most important saints. It is those more colorful saints that are likely to provide significant evidence of the liturgical use of the manuscript. You want to look for atypical saints, that is, saints who aren’t apostles, or early Roman martyrs, or Biblical characters such as Jesus, Mary Magdalene, John the Baptist, or the Virgin Mary. Saints in red or blue who are unusual are the clues you’re looking for. If those saints also appear in the litany or the suffrages, you know you’ve hit upon critical evidence for determining the Use of the manuscript.

Most of the red and blue saints in the New Bedford Hours are either of the Biblical variety or are typically French (such as St. Katherine or St. Egidius) and so are not of much use in localization; we already knew from stylistic evidence that the manuscript was from France. But one blue saint stands out: St. Ursinus, Bishop of Bourges, on June 11. In fact, St. Ursinus appears in this calendar four times: January 5 (the Octave, written in black), June 11 (his Translation, i.e. the commemoration of the movement of his relics from one place to another, in blue), November 9 (in black, the “Revelatio,” or revealing of his relics), and December 29 (in red). In addition, Ursinus appears in the litany, in the list of Confessors. Clearly, St. Ursinus was of particular importance to the patron of this manuscript. The next stop is the online “Zeitrechnung des Deutschen Mittelalters und der Neuzeit,” an online version of Hermann Grotefend’s dictionary of Saints. Each alphabetical entry gives the date(s) on which a particular saint was commemorated and where they were of particular importance. For Ursinus, however, Grotefend does not mention June 11. Time to break out the big guns.

The most detailed and lengthy dictionary of Saints is the Acta Sanctorum, begun by the Jesuit scholar Jean Bolland (1596 – 1665) in 1643 and carried on by the Société des Bollandists, who continue the work to this day. The Acta Sanctorum is organized calendrically and, like a great cathedral, is continually under construction; the 60+ published volumes cover only January through November. If you’re looking for a December date, you’re out of luck, since only an introduction to that month has been written so far. The volumes are enormous in size and copious in content, with each month filling three or four books. Many university libraries own the whole set, but if you can’t find it, you may be able to access it online through a library that subscribes to the Brepols Acta Sanctorum database. The digitized volumes are browseable through the Internet Archive and the URLs have been conveniently compiled here.

The most detailed and lengthy dictionary of Saints is the Acta Sanctorum, begun by the Jesuit scholar Jean Bolland (1596 – 1665) in 1643 and carried on by the Société des Bollandists, who continue the work to this day. The Acta Sanctorum is organized calendrically and, like a great cathedral, is continually under construction; the 60+ published volumes cover only January through November. If you’re looking for a December date, you’re out of luck, since only an introduction to that month has been written so far. The volumes are enormous in size and copious in content, with each month filling three or four books. Many university libraries own the whole set, but if you can’t find it, you may be able to access it online through a library that subscribes to the Brepols Acta Sanctorum database. The digitized volumes are browseable through the Internet Archive and the URLs have been conveniently compiled here.

The Acta Sanctorum is written entirely in Latin and provides transcriptions of Saints’ lives, tales of their relics and miracles, and important information about where they are venerated and on which days. According to the Acta Sanctorum, St. Ursinus – the patron of Évreux in the diocese of Lisieux in Normandy – was venerated in Évreux specifically on January 5, June 11, November 9, and December 29. Other saints of regional importance in the calendar include: Launomarus, Abbot of Chartres (January 19); Gatianus, Bishop of Tours (May 2); Translation of St. Audoenus, Archbishop of Rouen (May 5); Leufredus, Abbot of Merey (June 21, a date of particular import in Évreux); Ravennus and Rasiphus (July 23); Taurinus, Bishop of Évreux (July 23), Maurilius, Bishop of Angers (September 13); Mellonis, Bishop of Rouen (October 22, in red); Romanus, Archbishop of Rouen (October 23, in red); Briccius, Bishop of Tours (November 13); Anianus, Bishop of Orléans (November 17); and Gatianus, Archbishop of Tours (December 18).

This is all pretty clear evidence that the manuscript was made for a patron in or near Évreux. But there is more to do before drawing this conclusion with confidence. Does the rest of the liturgical evidence support this initial hypothesis?

This next piece is some hardcore liturgiology, so bear with me. It so happens that two deeply-buried portions of the liturgy in the Hours of the Virgin also point towards the Use of the manuscript: the antiphon and chapter reading for Prime and None. These can be difficult to find if you don’t have a lot of experience working with Books of Hours, but the miniatures can serve to orient you, just as they did for medieval readers. Prime is always illustrated by the Nativity, an easily recognizable scene (the Virgin Mary and Joseph gazing at Baby Jesus, surrounded by animals in a humble setting), and None by the Presentation in the Temple. Towards the end of each of these offices, you will find the antiphon (indicated by the rubric “Ant.”) and the chapter reading (indicated by the rubric “Cap.” for “capitula”). In the New Bedford Hours, the Prime Antiphon begins “Quando natus” and the Chapter reading begins “Ab initio et ante secula.” The next step is to make note of the antiphon and chapter reading in None, which is why it’s such a bummer that None is missing from this manuscript. It means that we only have half of the evidence.

Once you’ve made note of your antiphons and chapter readings, your next stop is another online resource, the extraordinary Book of Hours reference site authored by Erik Drigsdahl, who founded the Institute for the Study of Illuminated Manuscripts in Denmark and was its Director until his untimely death in 2015. Since that time, the website has remained viable thanks to the generosity and efforts of Peter Kidd. On this page in particular, you will find a very detailed list of these sets of antiphons and chapter readings, indicating where they’re used. There are many different Uses recorded for “Quando Natus” and “Ab initio” at Prime, and without the data for None we just can’t be sure. But even though None is missing, we can delve a bit further thanks to Drigsdahl’s recording complete outlines for several different local uses, including the Use of Lisieux. Even though so much of the Hours of the Virgin is missing from the New Bedford Hours, the extant texts are a near-perfect match to Drigsdahl’s outline. So Use of Lisieux seems likely, especially given the Lisieux emphasis in the Calendar.

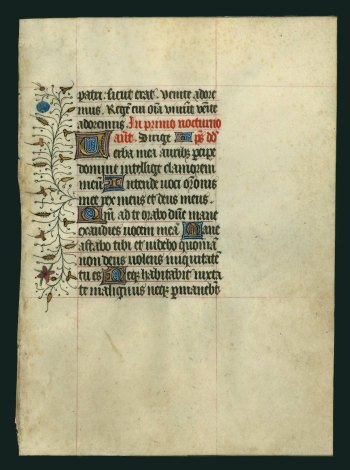

The final piece of the liturgical puzzle is found in the Office of the Dead. Here, you want to make note of the (usually) nine responsories of Matins. Matins is divided into three sections called nocturnes, each of which consists of a series of psalms and antiphons followed by a series of three readings, each of which is followed by a responsory. Those are the texts you’re looking for.

In the New Bedford Hours, the Responsories of the Office of the Dead are as follows:

1) Credo quod redemptor…

2) Qui lazarum…

3) Domine quando veneris…

4) Heu michi…

5) Ne recorderis…

6) Domine secundum actum meum noli…

7) Peccantem me cotidie…

8) Requiem eternam dona eis domine…

9) Libera me domine de morte…

Once you’ve found your nine responsories, the next stop is Knud Ottosen’s Responsories and Versicles of the Latin Office of the Dead. Fortunately, this, too, is available as an online resource. Ottosen’s methodology was to assign a number to each of the dozens of possible responsories used in Matins of the Office of the Dead. In this case, the numeric series is: 14 72 24 32 57 28 68 82 38. By looking up the numeric series here, you can determine where this particular series was used. The series in the New Bedford Hours turns out to be rather common, having been incorporated in the Sarum (a.k.a. Salisbury) liturgy among others. But it WAS used in Lisieux. When this evidence is combined with the evidence in the calendar, litany, and Hours of the Virgin, I think we’ve got enough to conclude that this manuscript was made for the use of someone in Évreux or elsewhere in the Lisieux diocese.

“The City of Evreux, Normandy, France,” published in Harper’s Weekly, January 1871

After all this, the hymns and suffrages are a bit anticlimactic: Sebastian, Katherine, Barbara, Blasian, the male and female “Privileged Saints” (Denis, Gregory, Christopher, Blasian, and Egidius and, for the women, Katherine, Margaret, Martha, and Barbara), Ivo, and Eustache. None of these are particularly localizable. I would’ve been very happy to see a hymn to St. Ursinus here, but so it goes.

Here’s the last bit. To determine if a Book of Hours was made for a female patron, turn to the Marian prayer “Obsecro te.” About two-thirds of the way through, you’ll find this phrase: “…atque momentis vitae meae et mihi famulo tuo impetres…” Or, if you’re lucky, you might find this: “…atque momentis vitae meae et mihi famulae tuae impetres…” Latinists will have spotted the difference between the two: the former is masculine, the latter feminine. If you’ve got the latter, you can confidently conclude that your book was written for a woman. If you’ve got the former, you can’t be sure either way, since the text could have been copied without “translating” the gender. On folio 68v of the New Bedford Hours, we find the masculine version, and so the gender of our Lisieux patron is not determinable.

Finally we have to ask the question I direct at all medieval manuscripts in North America: how did you get here? Unfortunately, we don’t know much.

The manuscript was acquired by the New Bedford Public Library in 1912, from New York bookdealer Lathrop C. Harper. I haven’t been able to find it in any of his catalogues (yet), and I have found no trace of it in the Schoenberg Database of Manuscripts. But we don’t need to find the Harper catalogue because the New Bedford Librarian very kindly transcribed it in his report to the Board of Directors in 1913:

“MS. Horae on Vellum—Horae Beatae Mariae Virginis cum Calendario, a Fifteenth Century French manuscript written in a large Gothic hand on 97 leaves of vellum, with nine large miniatures, nearly every leaf of the text decorated with a delicate floriated side border, the miniatures and some other pages being surrounded by similar, but rather more elaborate borders, 27 large illuminated initial letters, the smaller initials and the text also decorated (size 9 1-12 in. x 7 1-6 in.) in modern red velvet binding. g[ilt] e[dges]. Saec xv.”

In a report published several years later, the Librarian explained that he purchased the manuscript “a number of years ago, since it was deemed advisable that we should have in the library one sample of the beautiful work executed by the monks of the Middle Ages. The leaves of the book are vellum, and every letter and illustration is the handiwork of these mediaeval monks. Although a stiff price was paid for the book it would have been worth fully twice as much if the margins had not been cut in binding many years ago.”

Putting aside the librarian’s misconception about the origins of the volume (not written by monks but by professional guildsmen), these two descriptions provide important information: the book only had nine miniatures when the Library acquired it (in other words, it was already missing the lost leaves) and was bound in red velvet. It was bound in its current brown morocco leather after 1912.

Finally, by using the Hypertext Book of Hours, I was able to reconstruct the correct sequence of leaves and determine the missing sections. For those of you who care about such things, that information is detailed in my formal description of the manuscript: New Bedford Hours description

For 95 years, this beautiful Book of Hours has rested comfortably at the New Bedford Public Library, unknown, unrecorded, and unstudied. It is an instructive case study in how to interpret the evidence preserved in these medieval “best sellers,” but the manuscript also demonstrates that there is still material out there waiting to be brought to light.

For 95 years, this beautiful Book of Hours has rested comfortably at the New Bedford Public Library, unknown, unrecorded, and unstudied. It is an instructive case study in how to interpret the evidence preserved in these medieval “best sellers,” but the manuscript also demonstrates that there is still material out there waiting to be brought to light.

RESOURCES CITED (in order of use):

Melissa Conway and Lisa Fagin Davis, Directory of Collections in the United States and Canada with Pre-1600 Manuscript Holdings: http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/682342

Roger Wieck, Time Sanctified: http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/48460432

Les Enluminures, Book of Hours tutorial: http://www.medievalbooksofhours.com/learn

Hypertext Book of Hours: http://medievalist.net/hourstxt/home.htm

Hermann Grotefend, “Zeitrechnung des Deutschen Mittelalters und der Neuzeit”: http://bilder.manuscripta-mediaevalia.de/gaeste//grotefend/grotefend.htm

Acta Sanctorum database (subscription only): http://acta.chadwyck.co.uk/

Acta Sanctorum scans: http://www.roger-pearse.com/weblog/2012/06/19/volumes-of-the-acta-sanctorum-online/

Erik Drigsdahl, Book of Hours tutorial: http://manuscripts.org.uk/chd.dk/tutor/index.html

Knud Ottosen, Responsories and Versicles of the Latin Office of the Dead: http://www-app.uni-regensburg.de/Fakultaeten/PKGG/Musikwissenschaft/Cantus/Ottosen/search.html

Schoenberg Database of Manuscripts: https://sdbm.library.upenn.edu/

The Cipher of Roger Bacon is, quite frankly, a terrible piece of research. Presented as a formal and detailed linguistic and historical analysis, his logic is flawed and circular and his historical discussions are often not only bizarre but also anachronistic. The crux of his “solution” is the theory that each Voynich letter (or “grapheme,” more appropriately, since we don’t know for sure that they ARE letters…each character, for example, could be a phoneme) is actually a connected series of microscopic Latin letters strung together, written by none other than the thirteenth-century scholar and scientist

The Cipher of Roger Bacon is, quite frankly, a terrible piece of research. Presented as a formal and detailed linguistic and historical analysis, his logic is flawed and circular and his historical discussions are often not only bizarre but also anachronistic. The crux of his “solution” is the theory that each Voynich letter (or “grapheme,” more appropriately, since we don’t know for sure that they ARE letters…each character, for example, could be a phoneme) is actually a connected series of microscopic Latin letters strung together, written by none other than the thirteenth-century scholar and scientist

Montrose J. Moses’

Montrose J. Moses’  It was precisely because of Newbold’s widespread fame that Manly felt a moral imperative to publicly denounce his work, in the “interests of scientific truth.” “In my opinion,” he wrote, “the Newbold claims are entirely baseless and should be definitely and absolutely rejected” (Manly, p. 347). He goes on to spend fifty pages dismantling Newbold’s argument and methodology.

It was precisely because of Newbold’s widespread fame that Manly felt a moral imperative to publicly denounce his work, in the “interests of scientific truth.” “In my opinion,” he wrote, “the Newbold claims are entirely baseless and should be definitely and absolutely rejected” (Manly, p. 347). He goes on to spend fifty pages dismantling Newbold’s argument and methodology.

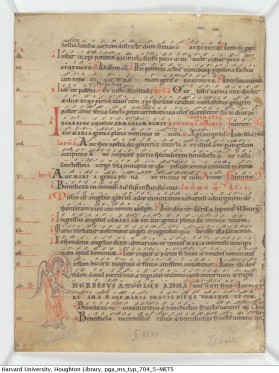

In its current state, the latter codex includes extracts from the Life and Miracles of St. Martin of Tours (attributed to the fourth-century French chronicler

In its current state, the latter codex includes extracts from the Life and Miracles of St. Martin of Tours (attributed to the fourth-century French chronicler  This is Phillipps MS 22049, acquired by Phillipps in the late 1860s (see Munby, A. N. L., The Formation of the Phillipps Library Between 1841 and 1872 (Phillipps Studies No. IV), p. 208) and sold from the collection at Sotheby’s on 6 June 1898, lot 841. It’s not clear when Father Murray acquired the manuscript, but it was likely in the early decades of the twentieth century.

This is Phillipps MS 22049, acquired by Phillipps in the late 1860s (see Munby, A. N. L., The Formation of the Phillipps Library Between 1841 and 1872 (Phillipps Studies No. IV), p. 208) and sold from the collection at Sotheby’s on 6 June 1898, lot 841. It’s not clear when Father Murray acquired the manuscript, but it was likely in the early decades of the twentieth century.

As we drove back to Saskatoon, dazzled by a blazing prairie sunset, we found ourselves wondering what Sir Thomas Phillipps would have thought about the fate of his MS 22049. I suspect he would have been puzzled at first (after all, the province of Saskatchewan didn’t exist until just a few years before his death). But as a collector himself, Phillipps would certainly have appreciated that the manuscript had found a happy home, first in the hands of the students’ beloved Père and now in the collection of the school he loved.

As we drove back to Saskatoon, dazzled by a blazing prairie sunset, we found ourselves wondering what Sir Thomas Phillipps would have thought about the fate of his MS 22049. I suspect he would have been puzzled at first (after all, the province of Saskatchewan didn’t exist until just a few years before his death). But as a collector himself, Phillipps would certainly have appreciated that the manuscript had found a happy home, first in the hands of the students’ beloved Père and now in the collection of the school he loved.

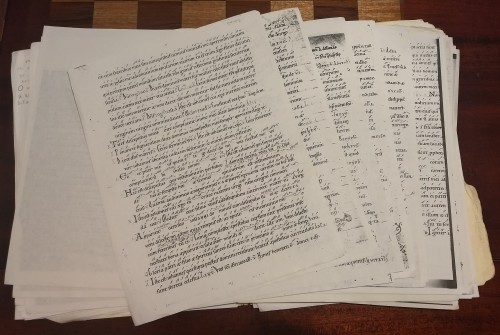

When I first studied the Gottschalk Antiphonal in the early 1990s, I did it with scissors and paste and black-and-white photocopies on the floor of my living room. It is truly thrilling to see it in glorious IIIF-compliant interoperable color in Fragmentarium. I hope that the reconstruction will complement the liturgical, art historical, and musicological study in my book, bringing this beautiful example of twelfth-century music, liturgy, and decoration to a new generation of students and scholars.

When I first studied the Gottschalk Antiphonal in the early 1990s, I did it with scissors and paste and black-and-white photocopies on the floor of my living room. It is truly thrilling to see it in glorious IIIF-compliant interoperable color in Fragmentarium. I hope that the reconstruction will complement the liturgical, art historical, and musicological study in my book, bringing this beautiful example of twelfth-century music, liturgy, and decoration to a new generation of students and scholars.

before Otto’s death in 1951, since he had once claimed that Series A had sold out by around 1940 (Gwara, p. 42). This set was likely acquired shortly before 1940, then, because by the time this set was purchased, certain leaves were already no longer available and Otto and Louise were offering substitutions. On the Broadside for this set, Louise notes, for example, that of leaf no. 4 (usually HL 54) there are only “a few left.” No. 2 (HL 59) was completely out of stock.

before Otto’s death in 1951, since he had once claimed that Series A had sold out by around 1940 (Gwara, p. 42). This set was likely acquired shortly before 1940, then, because by the time this set was purchased, certain leaves were already no longer available and Otto and Louise were offering substitutions. On the Broadside for this set, Louise notes, for example, that of leaf no. 4 (usually HL 54) there are only “a few left.” No. 2 (HL 59) was completely out of stock.

4 – 17 – 56

4 – 17 – 56

The most detailed and lengthy dictionary of Saints is the Acta Sanctorum, begun by the Jesuit scholar Jean Bolland (1596 – 1665) in 1643 and carried on by the

The most detailed and lengthy dictionary of Saints is the Acta Sanctorum, begun by the Jesuit scholar Jean Bolland (1596 – 1665) in 1643 and carried on by the

For 95 years, this beautiful Book of Hours has rested comfortably at the New Bedford Public Library, unknown, unrecorded, and unstudied. It is an instructive case study in how to interpret the evidence preserved in these medieval “best sellers,” but the manuscript also demonstrates that there is still material out there waiting to be brought to light.

For 95 years, this beautiful Book of Hours has rested comfortably at the New Bedford Public Library, unknown, unrecorded, and unstudied. It is an instructive case study in how to interpret the evidence preserved in these medieval “best sellers,” but the manuscript also demonstrates that there is still material out there waiting to be brought to light.

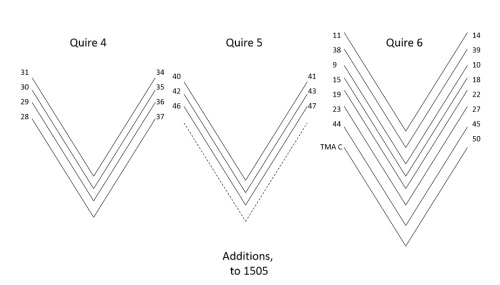

As part of my work cataloguing the more than 250 medieval and Renaissance manuscripts belonging to the Boston Public Library back in 2010-2012, I encountered a beautifully illuminated fourteenth-century manuscript that had been tentatively identified as a mariegola used by the Scuola della misericordia on Valverde, although there was no physical evidence to confirm this identification. At the time, it was known as manuscript f Med. 203. The manuscript comprises three sections that may or may not have been originally bound together: the original late fourteenth-century mariegola; additions up to the year 1505; and a blank register intended as a place for the brethren to sign their names.

As part of my work cataloguing the more than 250 medieval and Renaissance manuscripts belonging to the Boston Public Library back in 2010-2012, I encountered a beautifully illuminated fourteenth-century manuscript that had been tentatively identified as a mariegola used by the Scuola della misericordia on Valverde, although there was no physical evidence to confirm this identification. At the time, it was known as manuscript f Med. 203. The manuscript comprises three sections that may or may not have been originally bound together: the original late fourteenth-century mariegola; additions up to the year 1505; and a blank register intended as a place for the brethren to sign their names. Some contain images that refer directly to the rules that they introduce, such as the one on folio 8v (at right) of a Saint holding a votive candle that illustrates the chapter governing the use of candles in confraternity ritual.

Some contain images that refer directly to the rules that they introduce, such as the one on folio 8v (at right) of a Saint holding a votive candle that illustrates the chapter governing the use of candles in confraternity ritual.

In 1879, the manuscript went on permanent display in the Archive’s Queen Margerita Hall. It was described in the catalogue of 1880 as a “Mariegola of the Scuola di S. Maria di Valverde della Misericordia; parchment codex from the fourteenth century.” The catalogue goes on to describe the missing frontispiece: “The first page is illustrated with prophets and other saints surrounding the image of Christ bound to a column with brothers bowing before him. A large initial shows the Virgin with the infant upon her chest, sheltering a group of brothers beneath her mantel. The 42 chapters are illustrated with figures of saints, people and animals; original binding of brown calf with brass.”

In 1879, the manuscript went on permanent display in the Archive’s Queen Margerita Hall. It was described in the catalogue of 1880 as a “Mariegola of the Scuola di S. Maria di Valverde della Misericordia; parchment codex from the fourteenth century.” The catalogue goes on to describe the missing frontispiece: “The first page is illustrated with prophets and other saints surrounding the image of Christ bound to a column with brothers bowing before him. A large initial shows the Virgin with the infant upon her chest, sheltering a group of brothers beneath her mantel. The 42 chapters are illustrated with figures of saints, people and animals; original binding of brown calf with brass.”

In 1930, Lima librarian Georgie McAfee wrote to Ege after hearing him lecture, to propose an unusual scheme: the Lima Public Library would sell manuscript leaves as an agent for Ege, retaining a portion of the proceeds to benefit their Staff Loan Fund. The arrangement lasted for decades, continuing under the direction of Ege’s widow Louise after his death in 1951. Thousands of leaves were sold, and thousands of dollars were raised.

In 1930, Lima librarian Georgie McAfee wrote to Ege after hearing him lecture, to propose an unusual scheme: the Lima Public Library would sell manuscript leaves as an agent for Ege, retaining a portion of the proceeds to benefit their Staff Loan Fund. The arrangement lasted for decades, continuing under the direction of Ege’s widow Louise after his death in 1951. Thousands of leaves were sold, and thousands of dollars were raised.