Nobody really knows how Missouri came to be known as the “Show-Me State,” but I have my own interpretation of the state’s motto: Show me the manuscripts.

At last count, Missouri was home to 130 codices and 400 leaves in fifteen collections, most of which can be found on the I-70 corridor that runs across the state from Kansas City to St. Louis. Several of these are accessible through Digital Scriptorium: the University of Missouri – Columbia, Conception Abbey, the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, and St. Louis University. All of these collections have items worth pointing out, but I will focus on just a few:

The Ellis Library at the University of Missouri – Columbia owns a group of early fragments that once belonged to two collectors we have met before: Sir Thomas Phillipps (1792 – 1872) and Sir Sydney Cockerell (1867-1962). In fact, these leaves can be traced back as far as British antiquarian and bookseller John Bagford (1650s – 1716), a remarkable provenance indeed. The Bible fragment at left dates from the mid-tenth century and is not even the earliest of the group. That honor goes to the extraordinary fragment of Gregory the Great’s Moralia in Job shown below, attributed by the great paleographer Bernard Bischoff to Germany (perhaps Hersfeld), ca. 800.

One of the most interesting features of this fragment, aside from its age, is that it is written in an Anglo-Saxon hand but is thought to have originated in a German abbey, a remarkable mingling of scribal practices.

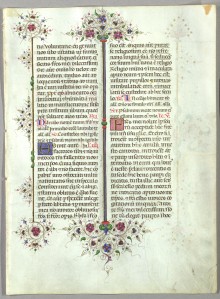

The Llangattock Breviary (St. Louis, Saint Louis University, Pius XII Memorial Library, Special Collections, VFL MS 2r)

In the impressive collection of the Pius XII Memorial Library at St. Louis University are found five leaves of a masterpiece of Renaissance illumination, a manuscript known as the Llangattock Breviary. Commissioned for the use of Leonello d’Este (1407-1450), Marchese of Ferrara, the manuscript’s name comes from a later owner, John Allan Rolls (1837-1912), Baron of Llangattock. The manuscript was bought by Goodspeeds Bookshop (Boston) in 1958 and subsequently broken up to be sold in pieces. Leaves can be found today in many collections, including Harvard University, U.C. Berkeley, the American Academy in Rome, Michigan State Univ., Univ. of South Carolina, the Hill Monastic Manuscript Library, Dartmouth College, the Museo Schifanoia in Ferrara, and the Bibliotheque Nationale de France (Ms. Lat. 9473, fol. 2). Leaves continue to come up for sale on a regular basis (here and here, for example). This is a manuscript that would be well worth the effort of digital reconstruction, a project just getting underway at St. Louis University. In the same building, the Vatican Film Library serves as a repository for microfilm of more than 37,000 manuscripts and is also the home of the St. Louis Conference on Manuscript Studies and the journal Manuscripta, making SLU an extremely important center for manuscript studies in North America.

Several dozen manuscript leaves were purchased in the mid-twentieth-century by the St. Louis Public Library. Here’s how they got there:

In the 1950s, a bookdealer from Kansas City, Missouri named Frank Glenn, under the auspices of a The Grolier Society (publishers of the well-known Book of Knowledge encyclopedia for children), assembled an exhibit of tablets, manuscripts and printed books meant to demonstrate the History of the Book. This was nothing new; similar exhibitions had taken place before, with similar pedagogical goals. But Glenn’s was different. Instead of making visitors come to a stationary exhibit space, or packing and shipping the exhibit from one venue to the next, Glenn installed the exhibit in an aluminum trailer and took it on the road.

Glenn toured dozens of cities and small towns around the U.S. and Canada over a period of several years, arranging tours for schools, churches and civic groups. The exhibit was called “The Magic Carpet on Wheels,” described in the accompanying pamphlet as “…a tribute to Johann Gutenberg,…The Magic Carpet on Wheels tells the story of The Miracle of the Book with more than 100 original specimens ranging from Sumerian cylinders of 2500 B.C. to fine examples of contemporary graphic arts. The exhibit is intended as a commemoration of the Gutenberg invention and as a tribute to those early scribes whose clay tablets, papyrus scrolls and illuminated manuscripts have been gathered here…Those who see these treasures will appreciate the personal qualities of love, pride and skill that have gone into writing and bookmaking for the 4,500-year period encompassed by the collection. The Grolier society hopes the items in the display will bring renewed interest and deepened understanding and appreciation of good books.”

Glenn toured dozens of cities and small towns around the U.S. and Canada over a period of several years, arranging tours for schools, churches and civic groups. The exhibit was called “The Magic Carpet on Wheels,” described in the accompanying pamphlet as “…a tribute to Johann Gutenberg,…The Magic Carpet on Wheels tells the story of The Miracle of the Book with more than 100 original specimens ranging from Sumerian cylinders of 2500 B.C. to fine examples of contemporary graphic arts. The exhibit is intended as a commemoration of the Gutenberg invention and as a tribute to those early scribes whose clay tablets, papyrus scrolls and illuminated manuscripts have been gathered here…Those who see these treasures will appreciate the personal qualities of love, pride and skill that have gone into writing and bookmaking for the 4,500-year period encompassed by the collection. The Grolier society hopes the items in the display will bring renewed interest and deepened understanding and appreciation of good books.”

The exhibit was a great success, if the dozens of thank-you notes archived by the St. Louis Public Library are to be believed: “We enjoyed going to the book exhibit. It is the first time our room has done that. We think that you explained everything real nicely. We also thought that it was well organized. / The things that we liked best was the hornbook because it was interesting to see what it looked like then, the music book, because it was so big and we don’t have anything like that today, and the beautiful backs of the books that had gold and other decorations on them. We also enjoyed finding out how the gold was polished in the illuminated letters. Sincerely yours, Pupils of McElroy Dagg School (North Kansas City, MO).”

The exhibit was a great success, if the dozens of thank-you notes archived by the St. Louis Public Library are to be believed: “We enjoyed going to the book exhibit. It is the first time our room has done that. We think that you explained everything real nicely. We also thought that it was well organized. / The things that we liked best was the hornbook because it was interesting to see what it looked like then, the music book, because it was so big and we don’t have anything like that today, and the beautiful backs of the books that had gold and other decorations on them. We also enjoyed finding out how the gold was polished in the illuminated letters. Sincerely yours, Pupils of McElroy Dagg School (North Kansas City, MO).”

Leaf from the Gottschalk Antiphonal (St. Louis Public Library, Grolier 44) (photo by Debra Cashion)

Some of the single leaves in the exhibit were purchased from Otto Ege, apparently one of his “Original Leaves from Famous Bibles” sets. Most came from other sources, including Number 44, a leaf of particular interest to me as it turned out to have come from the twelfth-century antiphonal that was the subject of my doctoral dissertation (and my first book).

In 1956, the manuscript leaves were purchased by the St. Louis Public Library.

Show me the manuscripts, indeed.